"Infancy assumes play."

Most historians ignore the gap between the appearance of our human ancestors in the savannah to the last million years there, evading the problems of the millions of years intervening. Desmond Morris in The Naked Ape, after indulging himself for about one page on this period, moves at once to the following statement: "This brings us to the last million or so years of the naked ape's ancestral history, and to a series of shattering and increasingly dramatic developments" . . . "the ancestral ground apes already had large and higher quality brains. They had good eyes and efficient grasping hands. They inevitably, as primates, had some degree of social organisation. With strong pressure on them to increase their prey-killing prowess, vital changes began to take place. They became more upright - fast, better runners. Their hands became freed from locomotion duties - strong, efficient weapon-holders. Their brain became more complex - brighter, quicker decision-makers. These things did not follow one another in a major set sequence; they blossomed together, minute advances being made first in one quality and then in another, each urging the other one. A hunting ape, a killer ape was in the making."

To me, it seems, mankind in the savannah was pathetic. These years of pathetic misery registered in mankind's brain and helped humans when they were able to think in abstract terms to create the idea of humaneness, another peculiarity of mankind.

We know that Australopithecus, who lived approximately a million and a half years ago, was about four feet tall with a brain capacity between 435-600 cubic centimeters, much the same as today's gorilla. Australopithecus' forebears, when they first came to the savannah about 16 million years ago, could not have been more than two feet six inches tall, with a brain a third of the size of today's gorilla. This frightened and feeble underdeveloped creature, by nature defenseless, and with no special talent or aptitude for life in his new environment, makes a laughingstock of the theories of most anthropologists.

But this human frailty and lack of specialization, in fact, became the main prop for survival in the savannah. If humans had been stronger and more specialized, like any other specialized animal in a new environment, they would have exhausted the potentialities of their specialization to an extreme degree, and become extinct as a species. Specialization has a quality of perseverance, which in any unnatural environment is fatal. As Russell stresses, an animal insists on following his instinct, either to his goal, or to his death.

By the close of the Miocene era, the basic human stock was living in the savannah, about to confront the Pliocene epoch, which lasted 13-1 million years ago. This was the most testing time in the history of mankind - an era of climatic deterioration and droughts which transformed Africa into a graveyard for many species. This climatically aggressive situation left a deep scar on the human old brain, a scar which influenced the mind in its creation of the first idea of hell. It says, in the Sumerian epic Inanna's Journey to Hell: "Here is no water but only rock, rock and no water and the sandy road" . . . In The Epic of Gilgamesh the writer states that "Hell is frightening because of its sandy dust" and because it is "the dead land" . . . It is "the river which has no water." In Inanna's Journey to Hell, when the goddess Inanna is revived from the dead and is ready to return to the land of the living, one of the judges of the nether world says: "Who has ever returned out of Hell unharmed?"

The variety of human types created by promiscuity was an advantage for the survival of the human species. Variety, or diversity in human individuals, helped, helps and will help humanity as a species to survive, as long as the fact is faced that humans lack an innate pattern of behavior and always face the threat of a change in environment. Some human individuals or groups, however abnormal they may appear to human assumptions of aesthetic, racial, psychological, or biological points of view, should never be suppressed by the majority of "normals." The suppression of the "inferior" by the "superior" threatens the continuation of the human species. With the possibility of continual change in the natural and cultural environment of mankind, anyone could (with reservations) be the "fittest." Any a priori, and even a posteriori meaning given to the idea of the fittest is ill advised, owing to the lack of specialization in the human species, and owing to the unpredictability of cultural and natural events.

Humans entered their new environment with no natural ability for surviving and with their instincts weakened by their hedonistic life. This lack of survivability urged them toward what became another peculiarity: improvisation. A specialized animal in a new environment is guided by his specialization; humans were guided by external circumstances.

What was the human group organization in the savannah?

With insecurity and anxiety about living, all manners of sensual pleasures developed. When men discovered the brain they added pleasures of the mind to sexual and sensual pleasures. Men have always been unscrupulous pursuers of pleasure and will remain so until one man, as a result of personal pleasure, triggers off a universal weapon that wipes out the entire species. Man is the only animal who kills for pleasure.

In the savannah, man's sex urge increased; even modern man's sex urge increases when anxious or panic-struck. During the Second World War those closest to the front line were obsessed by sex. Christian Europe was densely populated in the tenth century because the people feared the end of the world at the close of the first millennium.

In the savannah a phenomenon of great importance in the evolution of mankind occurred. The human male passed through a retrograde metamorphosis. He reverted to infancy. Even modern male, with all his intricately developed mental capacities, will, after any failure, revert to infancy. It is as if he wanted to become a child again in order to grow up and prepare himself all the better for a new life.

Our male ancestors started life in the savannah by regressing to neoteny, paedomorphosis, or to the Peter Pan evolutionary phase. In neoteny, the human male remained childlike in character all his life.

It was not a big backward step for man. He emerged from the woodlands, not only unspecialized but biologically retarded, and with weakened instincts, all attributable to his previously idyllic existence.

Many scientists agree that in the early stages there was an infantile phase in the savannah. Their belief is that it was mankind, both men and women, who went through this phase. It is my contention that if this were the case, we would not exist as a species today. It would have contradicted the elementary law of nature if a mother returned to infancy. A woman matures with pregnancy and acquires a feeling of responsibility toward the species. So in nature, the initiative and responsibility of the species belongs to the female.

The first historical evidence of a human mother suckling her infant comes from ancient Egypt, where, it is recorded, a child was breast-fed until it was three years old. In the savannah, many millions of years earlier, the child must have been breast-fed for much longer, and therefore for almost the greater part of man's life - man's life span then being much shorter.

Many scientists write in one paragraph that mankind faced a phase of infancy, often dedicating the next paragraph to the domineering and glorious male hunter, the generous and brave provider of food for his family. Infancy means dependence; infancy needs a mother, a mother's guidance. The instinct system in infancy is confused and unreliable, even in animals with a strong system of built-in reactions. The infant has to learn; the human infant even more so owing to his lack of specialization. The mother teaches him. Humans achieved a cultural instead of genetic transmission of patterns of behavior.

With the human males as infants, mankind in the savannah continued to be dominated by women.

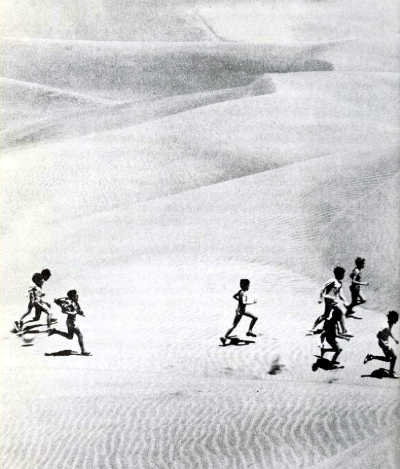

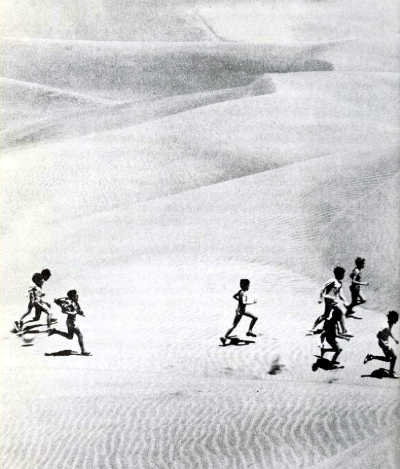

What does reverting to infancy mean in practical terms? Infancy assumes play. The human species owes its survival to play. Being an activity which explores the environment and is guided by curiosity (fed by what Schiller called "exuberant energy" typical in all infants, and in particular human infants), play has brought mankind to its most typical discovery: opportunism.

This permanent desire for new experiences, paramount in infancy through a greater sense of inquiry, became part of the nature of human males. It will always be nourished - for men feel that the new environment is not their natural one, but merely temporary, through which, by exploration, they will sooner or later find their lost paradise.

Curiosity, it seems, is a dispersion of nervous energy through the open senses. Man has more curiosity than other animals, not because he has more nervous energy, but because he has more open senses. Through these permanently open senses his nervous energy is in continuous contact with the external world. This nervous energy is never concentrated in one sense because the other senses remain open. Man might be compared with a sea monster with several extended feelers, feelers of different shapes, moving in all directions (movements inherited from life in the trees) to explore.

Man will always feel like a "tourist" in the new environment, a tourist in search of a temporary settlement. He will never involve himself wholeheartedly into any activity or specialization, as the feeling of provisoire dictates the motto of his life, "be prepared" - always ready for a new environment, another situation, another expulsion. Besides, for man, a biologically incomplete being, anything in nature can be put to some use. Even today, man, after a failure, never throws away a new chance.

That man considered existence in the savannah temporary is evident in that as soon as he discovered the creativity of his mind, he invented Paradises, Kingdoms of Heaven, Kingdoms of Gods and Utopias.

A specialized animal has at anyone time only one sensor shaped, for the dispersion of its nervous energy. This nervous energy ignores whatever does not accommodate the expectations of its open sensor. Young animals, because of their underdeveloped stage, are more curious than their parents.

Less specialized animals are more vulnerable, and therefore more curious. Highly specialized animals are rarely curious. Some people believe that curiosity is the result of intelligence. Both are the result of vulnerability and insecurity.

Exploratory play, an elastic, incomplete, and experimental activity, is what men will lean on to discover the best adaptation to their new environment. Play is, after all, the only activity which suits the nature of an incomplete animal such as man - an animal suffering from insufficiency. Play, which includes imitation, became man's only specialization, because it was the easiest way of adjusting to the variety of life in the new environment.

Huizinga considered that play was an irrational activity. We may consider it an irrational activity, but only because in our self-infatuation we consider ourselves purposeful, superior beings, beings with a self-acquired specialization, and with important roles in life. But despite our self-infatuation we are still simple opportunists, and play is the only rational activity for an opportunist; it is in keeping with his nature. The life of an opportunist is learning, permanent learning which can only be achieved through play. Learning, improvisation, and elasticity; these pre-eminent attributes of an opportunist are only possible through play. What is more, through play and exploration an opportunist achieves the essential and permanent aim of an unspecialized animal: to widen his living space. Here can be seen the rationality of play. Its purpose is to widen the possibilities for the life and survival of an opportunist. Any serious or purposeful activity in the new environment would have risked a clash, in which the loser would have been man.

In the savannah man felt imprisoned, as any animal in a new environment. With imprisonment even mature and specialized animals resort to play; probably because it is the only activity left to them in their desperate search for a means of survival.

This life of opportunism, discovered through play, had an important effect in perpetuating man's infancy for several million years. A life of exploratory play is filled with danger and accidents. Nature is not playful. Whenever man in play met the determination of a mature situation, or the result of a specialization, he would flee and run to his mother for protection, for encouragement, and for a new dose of infancy. Infants know only one reality: that of play; any other reality frightens them. The short life of humans in those days is another factor which perpetuated infancy in human males.

Human female found herself in the savannah with her maternal instinct of care for the young greatly increased owing to the male reversion to infancy. Even today man is by nature a dependent animal: in infancy he is guided by his mother; in adolescence by supernatural infatuation, by abstract ideas, or by beliefs. We will see later that man has never fully matured.

In the savannah, our mothers' ancestors soon developed, probably through their maternal instinct, the gift which has always remained with them: their easy adaptability to new circumstances. Woman was helped in her easy adaptability by her enhanced instinct for imitation.

From the start of their life in the savannah, man and woman behaved differently toward the environment. Man wanted to explore, and woman exploited his explorations. Man discovered how best to exploit circumstances; woman adapted herself to them.

Play taught mankind another lesson: "Nothing in excess." Millions of years later this became the motto at Delphi. Play helped humans in another way too. When they came out of the woodlands they were already individually more differentiated than any other species, through their sexual promiscuity. In the new environment play helped these individuals to develop their differences, the differences which contributed to the survival of mankind as a species. Faced with any new circumstance, there would always be at least one individual who would be able to face it somehow.

Play soon became a pleasure in itself. It suited human nature. It was the incomplete activity of an incomplete being. An incomplete activity leaves an unsatiated curiosity behind it. When animals play it is merely an exercise for their instincts and a training for their specialization. Play ceases with the start of their biological maturity. The animal and human infant share hiding and fleeing in common. These teach the most valuable behavior in nature. Escaping or hiding from danger is a natural and wise precaution. Only man (paradoxically only when man discovered his brain, or more precisely when he discovered his mind) has ever started to provoke danger. Courage has killed more men than anything else. Man considers courage a virtue. Animals consider it against nature, and therefore most unwise.

Man remained in this phase of childhood throughout the Pliocene epoch, which extended for nearly 12 million years. The reason for this protracted childhood was the continuing frustration of an opportunist's life in deteriorating climatic conditions.

The behavior of human beings today in certain revolutions and catastrophes is comparable to the behavior of our human ancestors in the savannah. A rejected or displaced person is closer to our human ancestors than a human fossil or an aborigine could ever be. One could compare our ancestors, evicted from the woodlands, with displaced persons after the Second World War, when the women immediately adapted themselves to their new life and environment, while the men vervy often reverted to infancy. When these rejected men were interviewed by immigration officers in America, they were like lost children, answering the question "What will you do in America?" with "Anything."

The economic miracle in Italy after the Second World War can be explained by the metamorphosis of the Italian men. After defeat and the fall of Fascism (and therefore the deflation of their self-infatuation), they reverted to infancy. They acquired a childlike enthusiasm and an eagerness to learn. Many authors have tried to explain the miraculous recovery of the Germans and the Japanese after defeat. Recognition of the failure of their adolescent self-infatuation brought them back to infancy and its optimism. In the case of the Germans we must also remember the infantile enthusiasm of the refugees from the East. And would England have become such a prosperous and industrialized country without the infantile enthusiasm such as that of the Huguenot immigrants? The economic productivity of the American worker and his achievements at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century were largely due to the enthusiasm of immigrants who had been rejected from all over the world for political, economic, or religious reasons. What is more, these American immigrants, just like our ancestors in the savannah, thought that their new life was only temporary. This gave America the rush and hurry which accelerated its rhythm of life.

After the 1917 Russian revolution, universities all over the world became inundated by Russian refugees. They were more youthful and enthusiastic than their young colleagues.

How many men today, afraid or disillusioned by the modern world of corruption, hypocrisy, and chicanery, prefer to revert to infancy and play with their own special noisy toys: sports cars, guns, and bombs, liable to cause all manner of social and economic disturbances or revolutions. Disturbances or revolutions have one thing in common with play: they have no purpose. They are the purpose. Nietzsche said that in every adult man "is hiding a child who wants to play."

It is very probable that the reason why human beings have a longer childhood than any other species of animal is due to man's reversion to infancy during the millions of years in the savannah. In the rest of the mammalian world infancy and prepuberty, the period between birth and sexual maturity, is, on average, a tenth to a twelfth part of the animal's whole life. For humans, until only a few centuries ago, it was nearly half their whole life. This long infancy, however, was vital to the life of an opportunist. An opportunist, without any innate pattern of behavior to help him, has to learn how to live. Perhaps this explains why an infant human's brain is only 23 per cent of its adult size, compared with 40 per cent in an infant orangutan, 45 per cent in an infant chimpanzee and 59 per cent in an infant gorilla. One year after birth, a chimpanzee's brain is fully grown. Some monkeys complete their brain growth within six months of birth. On average, humans take twenty-three years fully to develop theirs.

In their incompleteness, our ancestors found an ally to aid them in their survival in the savannah. Unconsciously, humans played the great game of nature; the display of strength. In this game, the survival of the least fit is guaranteed by his withdrawal at the first sign of a greater display of strength. Unexpectedly meeting dangerous predators, and being unable to escape, the humans would suddenly collapse, their bodies giving all signs of death. This apparent death was caused then, as it is caused today, by sudden terror. The muscles in the walls of the periferic blood vessels contract, blocking the flow of blood to the periferic organs of the human body, thus directing it to the vital central organs. As the arteria vertebralis and the arteria carotis and their branches, which supply blood to the brain are the periferic blood vessels, they contract, thereby stopping the blood coming to the brain, causing the syncope.

Life in the savannah meant organization and a division of labor. The female-dominated human group would find a protected spot under some isolated trees where the home would be formed and life would be organized. Mothers with offspring would hang from the branches, while the males went off in search of food. Man started life in the savannah by food gathering, bringing it back to his group in exchange for protection and sexual pleasure. Over the past millions of years, man has not changed. If man had not been in infancy, therefore dependent on women, and if his instinct for survival had been stronger than his need for biological comforts, he would never have returned with the food. With other primates, the group follows the males.

Even today, after millions of years of cultural, moral, and religious influence, man only shares what is his in return for comfort and security. From the earliest legal codes to the present there is a repetition of judicial norms which impose duties on man as far as the family's maintenance is concerned.

Man's selfishness increased during his phase of infancy. The females, aware of this characteristic, introduced a positive rule in their relationship: the rule of Do ut des. Man needed protection, comfort, and sexual pleasure; woman provided these in return for the food brought to her and the group. The more comfort or sexual pleasure he demanded, the harder he had to work for it.

A man today, away from home and away from the cultural, moral, or legal obligations imposed on him by his group, might behave in the same way as did his ancestors in the savannah. But instead of bringing food to earn his comforts and pleasure, he would take a woman out for dinner, hoping for the best afterward. He might even come to a financial arrangement from the start. Prostitution is another peculiarity of the human species.

Sharing food is indeed not in man's nature, and it is interesting to notice that men in the hippie communes of today are more generous with their priceless marijuana than with food.

The human group was dominated by a hierarchical order of females established by age. The eldest women were in charge.

In the savannah the older women used their memory, important factors in the life of a species that had to learn how to live. Before man became aware of his brain, he was still in the infancy phase, and infants, even when they develop a memory, seldom rely on it. In infants curiosity is stronger than memory. In order to rely on the memory, humans must acquire self-confidence. The hierarchical position produced this self-confidence.

Another proof that women must have been in charge of the human groups up until the adolescent revolution, which started about 25,000 years ago, is the human male's lack of efficient canine teeth. He must have lost them 20 million years ago during his dolce vita in the woodlands. Canine teeth in the animal world serve either for duels in the intra-specific selection with other males, or for fighting the enemies of the species for the protection of the young. In the mammalian world one of the supreme aims of the male, and one of the reasons for his existence after insemination of the female, is the protection of the new generation. The fact that man lost his canine teeth so many millions of years ago can have only one meaning, which is, that he did not fight for sexual predominance and that he did not protect the young of the species. After all, one could not ask men in the savannah to defend their infants when they themselves were in an infantile phase.

Humans, the males through exploration, the females through imitating men, became omnivores. Man, like any child who finds something new - eggs, small birds and young animals, insects, roots, plants, berries, meat from carcasses left by other animals - puts them straight into his mouth. By this method of trial and error, mankind discovered the human diet. Judging by the quantity of animal bones and skulls found near human fossils, marrow and brains were clearly part of the human diet. These were the only parts of an animal that predators would not eat.

Most scientists claim that men, as soon as they escaped to the savannah, started hunting, providing food for their families like medieval knights. In our conceit we have produced this romantic fallacy. Later I shall show how man is the only animal capable of self-deception.

One can make nonsense of this question of hunting by asking one simple question: How and with what weapons could man have hunted? As the spear was not invented until 30,000 years ago and the bow and arrow not until 12-15,000 years ago, I fail to see how this was possible. Man started his life in the savannah with neither natural nor artificial weapons. Hunting is an activity either dictated by instinct or by abstract thought, and man, prior to Homo sapiens, had neither. In his sheltered life of the woodland, he had lost his keen sense of smell, inherited from lower mammals. In the trees he had developed his sight; but in the savannah he needed to be more careful not to be seen, than to be able to see.

The human males food-gathered in packs. They started this by imitating other animals, particularly hyenas. They searched for carcasses killed by some lone predator, whom they would frighten from his feast by their vast numbers - or they would seek out a wounded animal.

Safety in numbers is yet another scar on our old brain which has fed and programed the human new brain, influencing man's creative thoughts. Overpopulation is probably also due to safety in numbers.

In the woodlands, fruit and leaves, plus the morning dew, was sufficient to quench human thirst. In the savannah humans became dependent on a source of drinking water, and could never stray far from lakes or rivers. Millions of years later, with the agricultural revolution of approximately the eighth millennium B.C., the first fixed settlements were founded near sources of drinking water.

Humans were weak, miserable, and clumsy creatures in the savannah of Africa, but a positive element was concealed in their weakness and clumsiness. Perhaps, when the brain started to create proverbs, this misery inspired the saying: "Good can come out of bad," a proverb repeated by mankind throughout history. Suddenly this unspecialized, unpredictable animal, this clumsy, uncoordinated, and inarticulate being in his unnatural environment, this discord in the natural harmony, became a frightening creature to other animals. Man became something to avoid, an attitude that animals adopt even today.

What is paradoxical is that these abnormal creatures, through their exploration of nature, learned a lesson: "Beware of freaks of nature." Disharmony in nature causes abnormal reactions. Harmony is harmless. "Beware of freaks of nature" was transformed by the ancient Romans into a moral rule, with their popular saying: Cave a signatis.

In Greek mythology Perseus kills Medusa. He is frightened by her ugliness.

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com