Index

| Parent Index

| Build Freedom:

Archive

PART 2

The Adolescent Revolution

"One of the oldest known statuettes . . . is of a fat and potent-looking lady."

"The first sculptures and paintings were the outcome of the artists playing with their imagination."

"Around 15-16,000 years ago there were cave paintings."

". . . the figures in the Valtorta cave . . ."

"If I am impressed by the aggression of a bull or the speed of a horse, I will impress my audience if I succeed in reproducing them."

"He was not impressed by any particular woman, as the heads and faces of the statuettes were only indicated, never elaborated."

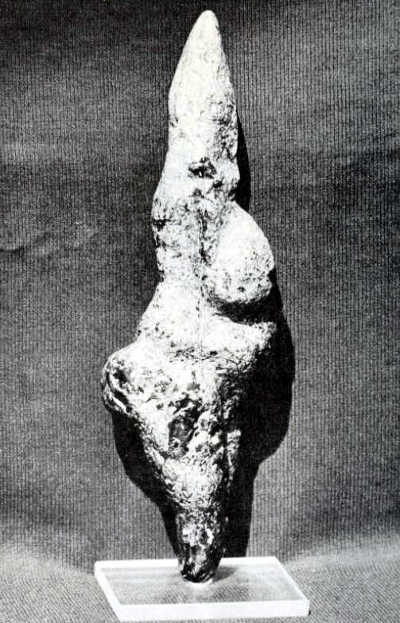

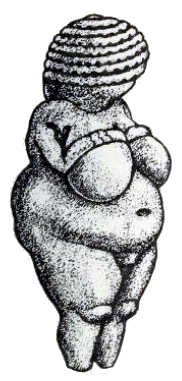

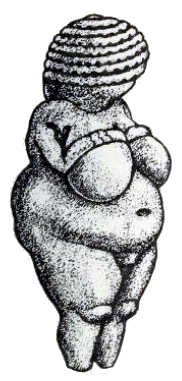

Why do we calculate that the beginning of Homo sapiens was during the Upper Paleolithic period? Because in that period we find the first signs of the mind's activity, in the form of art. One of the oldest known statuettes, "Venus of Laussel," a low relief carved on a block of limestone, is of a fat and potent-looking lady, and can be dated at around 27,000 years ago. A woman's torso, carved in hematite and 25,000 years old, was found in Ostrva Petrkovice in Czechoslovakia. Animals carved from stone and ivory 20,000 years ago were found at Württemberg, and a famous limestone statuette of a woman, 18,000 years old, was found in Willendorf in Austria. Around 15-16,000 years ago there were cave paintings.

Earlier than this art, there is no positive evidence of creative thought. How can we deduce this? One of the best definitions of art is still that of Aristotle. To him, "art is a capacity to make, involving a true course of thinking." Making, therefore, involves abstract thinking and there were no man-made objects before 27,000 years ago that "involved a true course of thinking."

We are talking about the mind and its creativity. But how did man discover the mind and its creativity?

When man became aware of the existence of his brain, he confronted it in the way he had faced anything new for millions of years. He played with it. The mind is the result of man playing with his brain.

The first sculptures and paintings were the outcome of the artists playing with their imagination. This is best illustrated in the paintings representing imaginary creatures, parts of various animals muddled together.

In the beginning, art was exploratory play. With the advance of the mind, play became a purposeful game. In this purposeful game art became symbolic, religious, magic or commercial. These were all open means for man to show off his superiority. With his mind, man entered the adolescent phase, the phase of competition.

Scientists disagree about the real meaning of the first known human art. For some it was an "art for art's sake"; for others a kind of "sympathetic magic and totemism." Many scientists feel that the first human art was a "fertility magic." Most of these speculations are based on the theory of so-called "ethnographic parallels," which means comparing the first human artist with those of present-day "primitives" - today's Australian aborigines, for example. This does not help very much, because today's "primitives," however primitive they may appear to the sophisticated observer, have a highly developed culture of their own.

If the first human art was "sympathetic magic and totemism," the figures represented would have been symbolic, and therefore stylized, and would not have exhibited a visual realism. Earlier cave art, and also the first statuettes, were representational art; it reproduced impressive images perceived from nature. Later, when humans developed their abstract ideas, more stylized representations were found, as in the figures of hunters in the Valtorta cave, and the Women dance from the Cogul cave. Both these paintings are from the Mesolithic period.

Later still the dissolution of figures representing abstract ideas reached extremes and became character symbols. This symbolic representation in paintings and engravings inspired Sumerian pictographic writing in the fourth millennium B.C.

The interpretation of the first human cave art as "fertility magic" can be disputed, for it was executed earlier than any notions of fertility. The notion of fertility developed around the eighth millennium B.C., with the first agricultural and the domestication of animals. It was then that the survival of the human species started depending on fertility. Of woman's fertility men could not possibly have any notion, let alone have given it any importance. There are no indisputable sexual signs or symbols, nor scenes of copulation of any kind in the "whole of Paleolithic art.

The interpretation "art for art's sake" cannot be very compelling either. If the first human painters had been capable of appreciating art for art's sake, surely there would be evidence that their minds had developed at a much earlier stage.

The fact that generation after generation painted over the same walls on top of existing paintings, contributes to the difficulty of interpreting the real meaning of the first human art.

In judging our first painters, scientists tend to attribute their own patterns of thought to them. We cannot attribute what the French like to call spiritualité to the mind at its dawn, when spiritualité was reached by the mind, thousands of years later.

Any artist, at the beginning of his artistic life and in his first work, finds himself in the same situation as the first human artist. With his first work, the first human artist wanted to impress, to realize an effect and to inspire admiration, admiration which implied his superiority.

What impressed others?

"What impresses me, helps me impress others," the artist says to himself. "Impressing others will put me in a superior position. If I am impressed by the aggression of a bull or the speed of a horse, I will impress my audience if I succeed in reproducing them." This was the simple reasoning of our first artists. Most of the cave paintings represented very impressive animals such as bison, horses, oxen, and mammoths. There were no landscapes, or paintings of trees and plants, lakes or rivers. The primitive humans were clearly not impressed by them, as they were part of their life. Paintings of birds were seldom found in the cave paintings, and hyenas never. There were also surprisingly few paintings of food animals, such as antelope, sheep, and goat, and also very few of man himself and of his first friend, the dog.

Impressive animals were usually depicted in an impressive manner, like bisons, the black painted stag with outstanding antlers, the black painted bull, horses and the "jumping cow," all from the Lascaux cave, or the red painted elephant in the El Castillo cave, the engraved bison in the La Greze cave, and the dying bison, the wild boar ready to charge in the Altamira cave. The look on the face of the savage cat in the Combarelles cave frightens visitors even today.

That the aim of the first artists was to impress can be deduced also from the representation of imaginary creatures such as the famous "Sorcerer" in Les Trois Frères cave.

What is the connection between an image in the mind and its exteriorization?

Any abstract idea craves to become reality. Impressed by his own abstract thought, an artist falls in love with it. It is his personal achievement and he has the urge to display it. He is in search of admiration which will give him the feeling of sufficiency, of completeness.

From the first human painters to modern adolescents, the story is the same - all like to show off their impressions. It makes them feel more important and less alone. Most adolescents, at the beginning of the abstract creativity of their mind, start a "journal" or diary in which they note their first impressions. Cave paintings, the "journal" of any adolescent, or the carving of initials on a tree or monument, have much in common.

Writers interpreting cave art as "sympathetic magic and totemism" or "fertility magic," or as "art for art's sake," did not study the drawings and inscriptions of adolescents on the walls of public lavatories all over the world, or the drawings and inscriptions of adolescents on the carriages of subways and buses in New York City. There they would find much in common with cave paintings. An American adolescent explained his "art" on the sides of subway carriages, in an interview with the New York Times. "I have carved my name all around. There ain't nowhere I go I can't see it. I sometimes go on Sunday to 7th Avenue and 86th Street station and just spend the whole day watching my name go by."

From the following historical text written by an Egyptian artist from the twentieth century B.C., we have an idea of the superior feelings of our first artists. "I was an artist, skilled in my art, excellent in my learning . . . I knew how to render the movements of a man and the carriage of a woman . . . and the speed of a runner. No one succeeds in all these things save only myself and the eldest son of my body."

Cave paintings have a strange characteristic and a certain mystery. The caves in which paintings were discovered were all inaccessible and dark. One has the impression that the first human art was painted in secret places.

At the beginning of the working of his mind, an adolescent will hide in caves or places protected from open spaces in order to find himself. Man could have started building a roof as much for psychological reasons, feelings of agoraphobia, as for climatic reasons. At the beginning of the working of his mind, an adolescent is frightened by the omnipotence of it, of its wilderness. Later, when the adolescent discovered the power of his mind and the power of beliefs, he invented gods, to protect him from the open spaces, the main characteristics of gods' being, in fact, their omnipresence. Whenever man becomes disillusioned by his gods he goes to the open spaces, into the wilderness, in search of new gods.

When man discovered his capacity for reproducing his impressions plastically, he obviously reproduced what impressed him most.

What was among man's first impressions when he became aware of his brain and of himse1f? Authority, the mother. Man was still a dependent being. He was not impressed by any particular woman, as the heads and faces of the statuettes were only indicated, never elaborated. It was women in general that impressed him, their authority, their solidity.

When the human male crosses the bridge into adolescence, he burns it, thus cutting the umbilical cord with the mother, the authority and organization which helped him to reach adolescence. He wants autonomy, he wants independence. The scars on his old brain engraved with our first fathers' separation in search of autonomy and independence, start to itch when man reaches adolescence. In any adolescent there is a Brutus trying to achieve his freedom by breaking with his Caesar. Brutus, Saint-Just rightly observed, had to kill Caesar, or kill himself. Marduk, in the first epic of creation of old Babylon, in order to become god, had to kill his mother.

How does male humanity achieve autonomy?

Rebellion! All rebellions and revolutions have one thing in common. They all aim for autonomy, liberation from the hierarchy, freedom from the past.

Autonomy is always fought for in the name of liberty, but once autonomy becomes established, the first thing that perishes is liberty. Violence and terror are the first stages in any adolescent autonomy. In this stage we have a new hierarchical order and new values which bring with them the seeds of a new rebellion, and so on. All rebellions of the human species are the same.

Here is the description of the first recorded rebellion by mankind. The quotations are from Admonitions by the sage Egyptian Ipuwer, written some forty-one centuries ago. "The King has been removed by the populace" . . . "The archives are destroyed, public offices are violated" . . . "The officials are murdered" . . . "A man takes his shield when he goes to plough. A man smites his brother, his mother's son" . . . "The poor man is full of joy" . . . "Gold is hoarded" . . . "The robber has riches, boxes of ebony are smashed. Precious acacia wood is cleft assunder" . . . "Every town says: 'Let us suppress the powerful among us' " . . . "She who looked at her face in the water is now the owner of a mirror" . . . "All female slaves are free with their tongues" . . . "The owners of robes are now in rags" . . . "Serfs have become the owners of serfs."

As Hegel rightly said: "What experience and history teach us is that people and governments have never learnt anything from history, or acted on principles deduced from it."

Going back to our first artists, in their first creativity phase they wanted to please the authority. As soon as they attained full adolescence, however, their aim was to impress their fellow adolescents. Adolescence is a phase of competition and antagonism.

The adolescent era also brought with it the characteristics of adolescence: envy and jealousy. The superiority of some was the inferiority of the others, which created envy, jealousy, suspicion, and tension. Fellow men will accept another man's superiority and leadership only if through this superiority they can achieve their own purpose, to be superior in some way as well.

What purpose did the first human male adolescents have in common? It was rebellion against woman and her domination. The barely accessible dark caves soon became the hiding place of the adolescents. There the first gang was born. From this primitive adolescent gang, gathering in the secrecy of a cave, to the cardinals of today meeting in a conclave, there is little difference.

With gangs, secrecy and conspiracy were born, the life blood of gangs. The hidden, dark cave suited the human male, frightened of being found out by the dominating mother and derided for his self-infatuation.

Through the cave meetings and cave paintings of our primitive ancestors, human males acquired new identities: the togetherness and solidarity of those in possession of a secret. Joining the gang, man entered into the role imposed by the gang, and an important feeling was born, a feeling of loyalty, loyalty to the common cause.

That the caves were places of initiation to a gang can be deduced by the considerable number of painted hands. On the walls of the El Castillo and Gargas caves there are about 182 paintings of hands, some crippled, some with missing fingers. In at least twenty other caves in France, Spain, and Italy, there are paintings of human hands.

Three facts emerge from these paintings. First, painting a hand is simple as one places it flat on the wall and traces round it, in and out of the fingers. This was the easiest initiation. Secondly, as most of the hands depicted were either mutilated or deformed, the caves must have been meeting places for the rejected humans living on the edge of the groups. There was no pity in premind human society. Physical abnormality was either rejected or feared as a freak of nature. The third fact proves that Paleolithic man was mainly right-handed. In the El Castillo and Gargas caves 159 were left hands and only 23 were right ones.

S. Giedion, a scientist who studied the meaning of the hands in the cave paintings, in his The Eternal Present, writes: "The cloud of mutilated hands at Gargas stands there like a tragic chorus eternally crying out for help and mercy." This passage proves that scientists judge the past in the light of their own prejudices, their own religious ideas. Mercy and charity developed much later, and only as an expedient of the mind. In the Roman salute of the first Nazi gangs, and in the revolutionary salute of the first anarchist gangs, many mutilated hands would have been evident, and they were certainly not pleading for mercy.

With adolescence the human male acquires another peculiarity: secrecy. In secrecy man feels protected from the outside world which might deride or challenge his self-created image of himself. In secrecy he feels safe in his own world of self-importance. Secrecy is the food of conceit.

Human male civilization was started by a gang in a cave, by a gang rebelling against an establishment, an order. Human male civilization, up until modern times, has never been anything but a civilization of gangs. The human male is lost without a gang. A gang is a substitute for the mother.

The first gang mentioned in history was the Babylonian "horde" from the Sumero-Akkadian Epic of Creation. The word "horde" was more appropriate in context with this epic, because the first organized adolescent rebels in Babylonia came mostly from the pastoral element. When the Goddess Tiamat gave her husband the "tables of destinies," the symbols of power, to encourage him in the war against the young gods, she said: "Your word will hold the rebel horde."

In essence there is no difference between the first gang of human males and the gangs of Napoleon and Hitler; no difference between Pericles' gang in the fifth century B.C., the Borgias in the fifteenth century or Christ's gang of the twelve apostles; no difference between the gang in White's Club, London, or a gang of Puerto Ricans on the West Side of New York City. All political parties and social classes are based on the mentality of the gang.

Two great writers of sociology, Mosca and Pareto call governing gangs "elites" or "ruling classes." Webster's dictionary gives the following definition of a gang: "A group of persons drawn together by a community of tastes, interests or activity." In this definition of the word one can see its origin and the characteristics of its components. What kind of a being needs a gang to achieve more than he could alone? Only a frightened and insufficient being; these are characteristics of the human male.

Ever since the first human adolescent revolution, up until the present day there is one gang stronger than the rest. This gang will always impose its "tastes, interests and activities" on the others. The more irrational the ideas and tastes, the more aggressive the gang, and the more aggressive the gang, the more successful it becomes. The history of mankind is a continuing example of this human logic. John Plamenatz, in his Democracy and Illusion, rightly stressed that it is not the rational side of religions or ideologies which appeals to the masses, but the irrational side. "Conscious and unconscious rebellion against the rational, respect given to Id at the expenses of ego, are hallmarks of our times," explains J. Monad in his Chance and Necessity. One thing I could add is that it was not the hallmarks of "our times," but that it has been the same ever since the beginning of the first adolescent revolution.

One cannot but smile at the paradoxical mentality of mankind reading and rereading the following words of Goethe: "It is the greatest joy of the man of thought, to have explored the explorable and then calmly to revere the inexplorable."

All gangs are aggressive. Aggression in an individual is caused by an individual mind and its idea of superiority. Jung, spurred on by Freud's individual unconsciousness, invented a collective one. I stress "invented," because no such thing exists in reality. In any gang there is a collective mind with a clear and positive idea of superiority. The Nazi gang was not guided by any "unconsciousness," but by a clear idea of superiority, the idea of Übermensch. The Nazis even gave scientific descriptions of "inferior-man," man to be eliminated. This was not a collective unconsciousness but a perfectly clear belief. The British gang of East India Trade robbed and exploited India, not in the name of "unconsciousness," but in the name of real interest inspired by two beliefs: belief in mercantilism and belief in British superiority.

Today everyone is scandalized by the activities of some young criminal gangs, robbing and destroying other people's property, but no one objects when the political party in power gives the responsible jobs in national economy to their incompetent or dishonest fellow believers, to the members of their gang.

In the Vatican, during the war, there were newspapers from countries all over the world. The German and Italian press called Roosevelt, "the leader of the Judeo-Masonic gang," Churchill, the leader of the "plutocratic and imperialistic gang," and Stalin, the leader of the "Asian, barbarian Communist gang." The Allied press referred to the German government as the "Nazi gang," and to the Italian government as the "Fascist gang."

The secret of a gang's success is secrecy. Karl Marx was right when he discovered that the purpose of secrecy was "mystification" on which any hierarchical system or any superiority leans.

Adolescents need to show off their secrecy to others in order to impress them with the superiority of belonging to a group. How did adolescents solve this problem of showing off a secret?

By inventing auto-decoration.

The most usual auto-decorations of humans are: tattooing, scarification, circumcision, hair styles, beards and mustaches, ties, badges, epaulettes, blazers and lately, jeans. There is little difference between Indian war paint, African tattoos, the Old Etonian tie, a Sicilian mafioso's sideburns, a teddy boy's leather jacket, and a cardinal's hat.

Justinian, confronted with the Nika Riot, followed the wise advice of his wife, Theodora. She knew the psychology of men and advised him to put on his imperial robes before presenting himself to the masses. "The purple is a glorious winding-sheet," she insisted.

From the ancient Huns to the Heidelberg students, men have tried to modify their looks in order to impress.

Some scientists claim that decoration is inherent in human nature; that it is an instinct. In my view, decoration is not inherent in human nature. It has been copied from animals. Animals display their innate bodily "aggressive signals," to impress.

That auto-decoration is not an instinct can be shown by the fact that all the human male's display signals are not innate but man-made signals, varying from culture to culture. The meaning of the display of decoration in the animal world, copied by the human male, is to impress, therefore to subdue, to subjugate the opponent. To an adolescent everyone is an opponent except the members of his own gang.

The human female also used, and still uses, auto-decoration. Unlike the male however, her intention is to seduce by pleasing, not to subdue by impressing.

Man's urge to permanently display decoration only proves that he is living in a permanent state of anxiety. An animal only displays his aggressive signals when frightened, when trying to impress.

The next step in auto-decoration was masquerading. This starts when man assumes a supernatural role. We have evidence that this pretentious behavior started in the Paleolithic epoch, soon after the mind began to feel self-confidence. By looking at the so-called "imaginary creatures" or the "fantastic beings," such as the "Sorcerer" in the Les Trois Frères cave, the "Dancer," with the bear head in the Le Mas d'Azil cave, and many creatures half animal, half man, we see man's desire to be supernatural.

Ceremonies and rituals started the decoration of the gang's collective ideas. From the ceremonies of the first gang, and those performed in the middle ages, to rituals in the Vatican and the Kremlin, there is little difference. They are all the same game, a decoration of the gang's beliefs, with the purpose of impressing.

What is the ultimate aim of impressing by ceremonies and rituals?

It is to achieve the subtlest of conquests: reverence, genuflection. Ceremonies and rituals are the life blood of collective beliefs.

One of the gods of the Vedic Pantheon, in 1500 B.C., was Agni, the god of ceremonies. The first hymn of Rig-Veda opens with the following verse: "I laud Agni the chosen priest, God, minister of sacrifice" . . .

K'ung, in the sixth century B.C., established ceremonies on all levels of Chinese life.

Perfumes are another achievement of humans, realized through the imitation of animals, who use their natural scent to impress, to please, or to seduce. Humans have used perfumes since prehistoric times. From the beginning of organized religions, perfumes, especially myrrh, were used in temples in order to create a seductive atmosphere. In ancient Egypt each god had his own "fragrance."

Most writers explain that at some point man became aware of the existence of his brain and started using it in a different way. They do not explain when and how it happened, however, or what man's first thoughts and his methods of thinking were.

The brain is the center of mental activity in both animals and humans. The most important mental activities are memory, intelligence intended as the power to understand objective reality, reasoning intended as the use of intelligence within the limits of the laws of nature, and the activity of abstract thought. The first three mental activities can be performed by some animals, but abstract thought can only be exercised by men.

How did man achieve this ability?

How and why did man begin using his brain for an independent activity? What happened?

The brain is like puberty: at a certain stage it starts to itch.

I have already stated that when man became aware of his brain, he faced it with the only activities that he knew: curiosity, play, and exploration. From playing with his brain he discovered abstract thought. Abstract thoughts are, therefore, the product of man's playing with his brain, an activity he may have discovered by analogy to sexual masturbation.

One of the first-known myths of creation, the old Egyptian myth, gives us an idea of the early working of the mind. When the Atum-Re discovered his mind, the Heliopolis myth explains, then he "who came into being of himself," created everything else: the universe, the visible and the invisible, the known and unknown. The god created the external world, as any adolescent creates his world, after his own image, his self-created image. "I planned in my heart how I should make every shape," stated the old Egyptian god.

How did the god create every shape?

"He put his penis in his hand for the pleasure of emission," explains the myth, "and there were born brother and sister" . . . From this "brother and sister" came the whole Egyptian pantheon of gods followed by man and woman.

In the Sumerian Enke and the World Order it is explained how their god of waters created Tigris, on which the life of the Sumerians depended. "He lifts his penis, ejaculates, thus filling the Tigris with sparkling waters."

Why did man take so long to discover his brain and to become aware of its existence?

There is evidence that 150-200,000 years ago the human brain was the same volume as that of Homo sapiens. Why then, did man only start using it for abstract reasoning about 30,000 years ago?

Curiosity and exploratory play are stronger in infants than memory. A child will play with the same toy over and over again if there is nothing more interesting to do. He has a memory but he does not trust it. A memory has no realistic meaning for him. It does not lean on anything which can give him confidence. Use of memory would be in contrast with an infant's nature; it would prevent playing and exploring. Without the use of memory there is no real abstract mental activity.

What was it then, that urged man to use his memory?

It was a sudden self-confidence which he acquired when, by playing with his brain he realized that he could produce wishful thoughts. No one really knows when man started playing with his brain, but we know that his first abstract thoughts came about 30,000 years ago. It was with this self-confidence that the era of adolescence started.

One of the first methods of thinking in order to reach abstract thought must have been analogy. This analogy at the beginning of man's abstract mental activity was of syllogistic character. There is evidence of this syllogistic reasoning in some of the Upper Paleolithic burial caves. Before the mind was discovered our ancestors had no idea of death. In these caves our ancestors coated their dead with red ochre. For them blood was a sign of life, blood was red, therefore red signified the source of life. We can find this kind of thinking today in some forms of schizophrenic, archaic reasoning.

Man made yet another discovery while playing with his brain. He discovered the idea of truth, an important discovery for a creature with no innate pattern of behavior. Truth became the repetition of natural events. Heraclitus understood this when he said: "It follows that the coming-to-be of anything, if it is absolutely necessary, must be cyclical - i.e. must return upon itself."

With the development of the mind, alas, man discovered what Plato called "useful lies." The human mind, realizing that truth was the repetition of an event, succeeded to fool itself by the artificial or verbal repetition of useful lies, thus transforming them into truths. Political and religious propaganda is based on this syllogism. This syllogism produced the mind's damaging invention-rhetoric.

What is an abstract idea, and how did man achieve it?

An abstract idea is nothing but the wishful thinking of an incomplete being concerning the unknown, the unexplored, or the inexplorable. The ancient Egyptians were right when they placed the source of the mind in the heart. Wishful thinking soon became a belief on which man could lean in order to find peace when confronted with the unexplored. The unexplored had to be explained through wishful thinking or wishful belief, otherwise man could not enjoy the explored. He would be too frightened.

Man, being an opportunist in permanent search of a better adaptation, is an explorer by nature. An explorer will always be attracted to the unexplored.

Why?

There is only one way a curious and incomplete being sees the unexplored: optimistically, hopefully, wishfully.

When the brain discovered the mind, or its capacity for creating abstract thoughts or wishful thinking, it became so proud of it that it became a slave to it. It is the nature of the creation to enslave the creator.

What happened to the other activity of the brain, its intelligence, intelligence intended as the understanding of nature and its laws? The brain's intelligence became a blind servant of the mind's creation, belief. Man started seeing nature with eyes focused by the mind. Reality became "ought to be reality."

In discovering its power to create abstract thoughts, the mind started flirting with itself, worshiping itself. Man succeeded where no animal would ever succeed - to flatter himself and, what is more, to believe in his own flattery. Why?

The answer is that any abstract thinking is always wishful thinking.

Fascinated by the power of his mind and unhappy with his unnatural environment and his position in it, man started creating an abstract environment to suit himself, or rather his wishful image of himself. In his transcendental world man imagined himself the way he thought he should be as a complete being.

With the mind man discovered a new pleasure, the pleasure of his mind. This pleasure became the main drive of the human male's behavior. Even sexual and sensual pleasures became subordinated to the pleasure of the mind. Fervent believers are seldom interested in the pleasures of sex.

What is this power of the mind?

It is the ability to create ideas about oneself and the world. But ideas cannot exist by themselves, they need help. Passion and love were added to the adolescent mind's creation, the idea. Only man can love, only man can have illusions. What we call the love of children is nothing but a biological comfort. What we call love of women for men is nothing but a biological, mental, and financial comfort, or an adaptation to the new element in the environment, man's love of his ideas. A woman's attitude towards her children is dictated by her maternal instinct, which stems from concern for the good of the progeny. Lacking a maternal instinct, a woman imitates man and develops love for her children which, in essence, is love for herself, her psychological, biological, or social comforts. It has nothing to do with the good of the progeny.

The only possible love is the love of an idea, of an abstract creation. The idea can only survive if leaning on love; it has no natural roots. Love, too, being an abstract phenomenon has to lean on something. It invents beliefs. Love, in order to exist, has to blind itself by beliefs. A belief is the guardian of blindncess, the protector of ideas from their enemy, objective reality. Belief becomes a defender of the supernatural against the natural. But belief, too, has to lean on something to exist. It finds its strength in its own invention, in arrogance. Beliefs put their creator in artificially superior positions, positions which have to be defended. In arrogance, this protective shield of the supernatural, lies the origin of a unique aggression in nature. We will call this man-made aggression, a believer's aggression. The source of man's aggression lies in his mind.

"Love and do what you want," said St. Augustine, meaning, presumably, religious love, the love of an idea. In the name of the love of Jesus, Christians have committed numerous crimes. The main evil deeds are not committed out of hatred but out of love, the love of an idea. Only a believer can be evil. Solzhenitsyn was right when he said: "To do evil a human being first of all must believe that what he is doing is good."

Aggression started with the mind. Aggression is the use of physical strength in defending an abstract world against enemies. The enemies of beliefs, from the first believer to Stalin, are always the same. They are non-believers in their own beliefs. "Who is not with me is against me," is the motto of all believers. The adolescent era is the era of partisans. Only a partisan of Christ can conceive the idea of an anti-Christ.

Humanity, ever since it entered the phase of beliefs, has not changed regarding the extermination of opponents, the infidels or the other side. From Sumerian or Egyptian believers to contemporary believers, there has been no difference in dealing with the enemy. Here I quote a description of an Egyptian historian and general, Weni, of 4,400 years ago, about his punitive expedition against his enemies, against non-believers, non-believers in Egyptian superiority. He calls his enemies by the denigrating name of "sand-dwellers." He wrote:

The army returned in peace, it had cut down

Its figs and wines.

This army returned in peace, it had cast fire

Into all its princely houses.

This army returned in peace, it had slain troops

In many tens of thousands.

This army returned in peace, it had carried away

Many troops as prisoners.

And his Majesty praised me on account of it more than anything.

The use of physical violence in defending or imposing beliefs has not changed since the first believer right up to the modern extremists. The former used his muscles, the latter knives, guns, or bombs.

In play, a child or a man in infancy is an instrument of his play. He is his own toy, he is his own train, his own horse, etc. He is a third person. With the discovery of the mind, a human male enters the adolescent phase, he enters into the first person.

With his mind man saw himself, or more accurately he created himself. Until then, like any other animal, he only knew the outside world, the universe without him. When man created himself he fell in love with himself, he became the universe, the center of the universe. With the mind, man assumed a role, a role given to him by his own mind. He abandoned childish play and entered into a game, the game of roles. Life became a theater. Men started acting life instead of living it. Only a being living a life of roles could have had the idea of writing for the stage.

The women and children accepted this new way of life, the women by adapting themselves, by imitating the game of roles, and the children by playing with them. In the theatrical life of an adolescent there are two main characters: man in the role of Don Quixote, woman in the role of Sancho Panza. Ortega y Gasset was right when he wrote: "The woman goes to the theatre; the man carries it inside himself and is the impresario of his own life."

Assumed roles imposed by abstract beliefs need affirmation. Adolescents soon create competition. They think it gives life to the assumed roles. Competition is an absurdity in the life of an opportunist. The nature of an opportunist needs collaboration and consensus. In modern history competition is considered an economic value. But in logical terms competition is the destruction of resources. There is no competition which can produce more than co-operation.

Competition is in the nature of adolescents. Competition produces victims, and the human male needs victims to feel self-confident, to feel superior. Men, or gangs of men, will always invent and impose the game in which they excel, giving themselves a better chance of winning.

What is the real aim of a game, this invention of man in his adolescent phase? Do games produce victories or victor? From the point of view of natural logic, a game cannot produce victory, only a victor. Who then is the victor? The victor is whoever provides a loser, the loser being proof of the victor's superiority. The only positive realization of games, activities of competition and antagonism are, therefore, losers.

Huizinga was inaccurate when he said that play was an irrational activity. It is games that are the irrational activities.

Man discovered the power of his mind and the power of self-infatuation. These powers inspired arrogance in him and the audacity to use his physical strength. Before Homo sapiens, the use of physical strength was not practiced by humans. We do not know if man, before becoming sapiens was stronger than woman, but his audacity in using his physical strength put him a position to be stronger than woman. Woman's instinct of adaptation helped him.

The audacity of man is unique. The word comes from the Latin audere, meaning to dare, to defy laws and rules. What animal could defy the rules of nature? Only an incomplete animal, an animal without innate rules, without an innate pattern of behavior, only an animal who had nothing to lose, an animal able to invent "Après moi le déluge" would dare to be audacious. Man started breaking the pattern of life based on woman's natural superiority, a pattern that had existed for millions of years.

The adolescent revolution introduced a radical change in sexual relationships. Instead of being seduced by the female, therefore reduced to the position of a pleasing slave, an obedient servant, the male wanted to seduce. He wanted to reduce woman to his slave and servant.

But what were his means of seduction?

Zeus pursuing Semele, mother of Dionysus.

"Man became obsessed with virility."

"Man invented a mask. . ."

Seduction presupposes superiority. What was this superiority? Man's only superiority over woman was his readiness to use his physical strength. He perpetrated the first incongruity of his new life, he used force and violence to seduce. He substituted woman's promiscuity with his own. The more women he had sexual intercourse with, the more powerful he felt. Man became obsessed with virility. The cult of the bull was born at the dawn of man's adolescent revolution, and the bull, the symbol of "genetic strength" became a sacred animal to man. From the Upper Paleolithic cave paintings, and the sculptures of the Çatal Hüyük shrines of the seventh millennium B.C., to the figurines of Starĉevo and Vinĉa of the fifth millennium B.C., bulls are a prominent feature in art.

"Many Greeks reproduce Dionysus' image in the form of a bull," stressed Plutarch. Even Zeus transformed himself into a bull in order to seduce Europa.

The following passage from the Iliad shows Zeus extolling his virility on seducing Hera: "Today let us enjoy the delights of love. Never has such desire, for goddess or woman flooded and overwhelmed my heart; not even when I loved Ixion's life, who bore Pirithous to rival the gods in wisdom; or Danae of the slim ankles, the daughter of Aerisius who gave birth to Perseus, the greatest hero of his time; or the far-famed daughter of Phoenix, who bore me Minos and the godlike Rhadamanthus; or Semele, or Alemene in Thebes whose son was the lion-hearted Heracles, while Semele bore Dionysus to give pleasure to Mankind; or Demeter, Queen of the lovely locks, or the incomparable Leto; or when I fell in love with you yourself, never have I felt such love, such sweet desire, as fills me now for you."

Man soon realized the difficulty of keeping woman with his virility. He then reduced her to his slave by using moral, religious, legal and economic coercion. Lack of virility was solved by forbidding his woman to have sexual intercourse with anyone but him, punishing her adultery with death. In some Latin countries until very recently, women were killed for adultery.

The promiscuous women who did not wish to conform to the rules imposed on them by men were rejected and often persecuted. They were labeled harlots or other such names of contempt. The following old Babylonian advice is typical of the adolescent male's opinion of female rebels: "Do not marry a harlot whose husbands are 6,000."

After his successful adolescent revolution, man wanted to differ physically even more from women. In the drawings, engravings and sculptures of the Indo-European, Sumerian, Assyrian or Greek early history, the first peoples to liberate themselves from women, men are depicted with beards and are dressed differently from women. In places where the adolescent revolution took longer to succeed, the men in the pictures are clean-shaven and dressed in the same way as women. The reason that man was depicted without a beard in female-dominated societies was that either the beard only started to grow when man emerged from his infancy phase, or because man wanted to be similar to woman in appearance.

The mind, putting man in a supernatural position, changed everything. Life, which in nature is a purpose in itself, became for man an instrument for his beliefs. Life became a slave of beliefs. Men started killing themselves and their fellow men and even their own flesh and blood in the name of their beliefs.

How did man reach this absurd situation?

Adolescent humanity was trying to be what, by nature, it was not. The mind invented "ought to be." "That short but imperious word 'ought,' so full of high significance," explained Darwin. Man achieved what no animal or woman will ever achieve: not to be himself, but to become his own wishful thinking. Man became what his mind dictated to him that he ought to be. The "ought to be" became his life in spite of nature, and against nature.

Man's invention of "ought to be" is evidence that he has no "be," that he is not a complete being, that he is a "becoming" being. A becoming being never reaches maturity. Since the invention of "ought to be" the human pattern of behavior started relying on it. Man became his own most obedient servant. From being his own servant to becoming others' servant, from "ought to be" to the categorical imperative of "thou shalt," the step was short.

Man imposes on himself a role in the game of life, a role inspired by his mind. Man invented a mask and put it over his face, over his whole being; the mask represented the "ought." Only man's mind, this creator of "oughts" could have thought up the idea of a mask. The mask pretends to be something or someone else.

Prehistory offers us a variety of artistic representations of masks. The Vinĉa and Starĉevo artists in the sixth millennium B.C.

dedicated their skill with a particular enthusiasm to sculptural masks.

In several languages, even today, men address each other in the third person as if addressing a mask.

The "ought to be," reflecting a transcendental world, brought man out of the real world. Ever since the mind began to create abstract ideas, no man ever lived in this world, he lived, and still lives in his own world, imprisoned there by his own beliefs.

We may ask if beliefs, those discoveries of male humanity and imposed on the women and children, were any good to the human species and its future.

Beliefs bring aggression, human aggression, the most evil aggression in nature. But what is even more dangerous is that beliefs reduce curiosity and exploration, the most important factors in the life of the human species. In this sense, beliefs become what specializations are for highly specialized animals; both reduce curiosity; both are only interested in what suits their limited fields. Beliefs halt progress, progress toward better harmony with the universe. Belief considers itself perfect. Perfection does not allow for curiosity or exploration. It therefore causes stagnation or regression.

When human males discovered their brain, and through it their mind, and through their mind the idea of superiority and through this superiority, aggression, they started to use this aggression, not only against their mothers, but against other human groups as well.

Between 20-30,000 years ago, our ancestors began writing the history of Homo sapiens with the blood of the innocent. They suppressed their cousins of the Neanderthal type who were still in infancy. By 20,000 years ago the adolescent gangs of our direct ancestors succeeded in eliminating from the face of the earth, all the lesser-developed human groups. Ever since then the self-assertion of a human group has been at the expense of other groups.

The first adolescent revolution was a slow but gradual process starting with Homo sapiens and going on until approximately the third century A.D. Its main characteristic was rebellion against women and their dominating role in society, in the name of man's abstract thought. With adolescence a new male humanity was born.

Ritualistic ceremonies in many cultures have been performed ever since the beginning of history, and always at the start of the adolescent phase. The meaning of all these ceremonies is always the same; the death of one being and the birth of another; the birth of a new personality, which has nothing to do with the dead one. In a number of ancient myths, a boy is swallowed by a monster and then rejected by it, but as a new being, the monster giving to that new being during his transition a new personality, leaving scars or tooth marks on him.

There are many rituals in history indicating the transition from childhood to adolescence, but not one shows us the transition from adolescence to adulthood. In my view, male humanity has never advanced beyond the stage of adolescence.

I am aware that my theory of adolescence as a new phase of life independent of childhood in the human male, will be questioned by many psychiatrists and psychoanalysts. To them childhood is the basis of future man; it explains everything. But so does instinct for sociologists and economists; so does God for the religious; and the palm of the hand for fortunetellers.

But are any of these explanations true?

In my view, many scientists exaggerate in their speculations about childhood. Freud illustrated his preconceived ideas with a number of so-called "clinical examples." But did they really exist or were they invented, invented to suit his metaphysical speculations? Why did Freud and his followers not illustrate the thousands of examples which contradicted his thesis? Freud and his followers suffer, as Bertrand Russell rightly stressed, from Hegelian illusions which in practical terms means that they see in childhood what their abstract preconceived thought needs to see. Perhaps this is why their methods treat the mentally disturbed but do not cure them.

Adolescence, being a phase of beliefs, therefore a phase of doubts and conversions, has nothing to do with the innocent play and exploration of childhood.

It is not childhood that determines the personality of adolescence. It is playing with the brain, building up the mind which is of essential importance for future life. This starts at the threshold of adolescence. As science has dedicated no efforts to this important period in man's life, the period of the formation of his ideas about himself, no one has ever explained what really happens at this stage. No one really knows how and why, out of a charming and gay boy, a rude and gloomy adolescent suddenly emerges; why a clean and honest child grows into a cheat, a liar, or a thief.

A human adolescent cannot judge or analyze childhood. It is a different world with different values and a different language; one is purposeless exploratory play. the second a purposeful game. Man judges childhood as he judges everything else: by himself, by his own ideas, by his mind. We think our children are aggressive only because we are aggressive. A gangster will see a gangster in every child. A Freudian will find that every child suffers from the Oedipus and other complexes. A sex maniac will see a sex maniac in every child. A perverse or cruel adolescent will claim that a child's exploratory play with animals is perverse or cruel.

Freud, before being a scientist, was an adolescent human being, and the nature of adolescent humanity is to judge everything and everyone, throughout history, by the mind, by preconceptions or metaphysical speculations, in relation to abstract ideas.

That Freud was the prototype of adolescence can be deduced from his gloominess. Adolescence is a gloomy stage.

Helmut Schulze points out that Freud never mentions the word joy in any of his works. Adolescents are only aware of achievements, victories compensated by orgasmic pleasure which leaves them in the well-known post-orgasmic depression.

Childhood, through exploration and play, is a preparation for an opportunistic life. When the child becomes an adolescent, however, he enters an idealistic world in which he obeys a role, he obeys the beliefs of his mind. It is not the childhood experiences which influence his adolescent idea about himself and his romantic place in the world. It is conceit, once formed, that finds its justification or interpretations in childhood. Between the two world wars a large number of British and French upper-class adolescents, with happy, normal backgrounds, chose, out of pure exhibitionism, following an intellectual fashion, to become Communists. They all found justifying experiences for their attitudes from their childhood, because they looked back on this period of their lives with the minds of Communists. Many of these British and French Communists found justifying experiences for their conversion to Catholicism, Humanism, alcoholism, and homosexuality in the same childhood. The repeated conversions of human beings prove that childhood is only a reservoir of experiences to be interpreted, chosen, as the justifying element for changing the mind. Childhood could be compared to a library where one goes to choose the book suited to one's frame of mind at that moment. Looking back on his life, an old man will see how many times his beliefs, loves, etc. have changed. His childhood, however, remains the same one.

Human males in the adolescent phase always find an excuse in their childhood to justify any change of belief. Adolescents cannot live with the feeling of responsibility. If they fail to find their own excuses, psychiatrists will help, and together they will be satisfied in their illusions.

Adolescents do not like to give the impression that they change their beliefs or ideas. Above all they hate to be reminded of their previous beliefs or loves. Adolescents are always suspicious of people who remember.

Childhood bears no relation to the personality of the adolescent, as claimed by psychiatrists of today. This is evident from the first major move the adolescent makes. The adolescent's first step, which makes him "adult" in his mind, is his own independence of mind. He dreams of separation, a separation from the past, an abrupt rupture with the past.

Between infancy and adolescence, there is a third large group of humanity which stops and lives on a bridge between the two. This third group of humans grew out of play and exploration, but never reached the purposeful games or beliefs of adolescents. This group became obsessed by novelty, novelty imposed by propaganda, the fashion or latest trend. Novelty became the purpose. This group lives in the phase of neophilia. Living for novelty gives this sterile humanity a lasting feeling of growing up, of becoming the future. That is how they try to find their identity, their feeling of superiority; the protection of being "with it."

Man's vanity, pretentiousness, arrogance, aggressiveness, and his urge to impress, are all signs of the fragility, of his unnatural position in a natural world. When one reads the definition of a schizoid, it is like reading the definition of adolescent male humanity. (. . . "being susceptible to any criticism or situation which threatens the position, assumed attitude of superiority.") Schizophrenia, paranoia, depressions, suicide, or murder do not exist in children. They all start with adolescence, with the development of the mind.

We all agree that men are egotistical, selfish, and aggressive, but these are the characteristics of any psychopath. This is not surprising, however, considering that adolescence is the vulnerable phase of an incomplete and ambitious being. Conceit, self-indulgence, self-centeredness, intolerance, pride, vanity, capriciousness, animosity, spitefulness, revenge, resentfulness, envy, jealousy, hatred, cruelty, agony, ecstasy, and above all self-confidence and self-esteem, are the main characteristics of male humanity in their adolescent phase.

What, we might ask, inspires these characteristics in man?

Belief of superiority is the cause of all these.

Adolescence is an obstinate stage. Occasionally an adolescent reaches the apex of obstinacy, when he believes in miracles.

Adolescents are afraid of the truth. Adolescence is a stage of beliefs, each belief having its own truth. Pascal said: "We make an ideal of truth." In fact man does the opposite; he makes the truth out of an ideal. Without humility man cannot know the truth. The truth is always humiliating for man, which is why he prefers beliefs.

Man lives in an intoxicated state of narcissism until he dies. Any woman will tell you how pathetic man, living among the illusions created by his mind, can be, and how easily he is seduced if these illusions are flattered.

There is nothing more pathetic than an old adolescent faced with reality, a reality which cannot be treated with illusions, the reality of death. When the idea of death enters the head of an old male adolescent, a comedy takes place. Reading the morning papers, he will say to himself: "Life is not worth living any more; the world is going to the dogs." As man is the only animal capable of brainwashing himself, he will convince himself that the "new world" is not for him or his "dignity," thereby fooling himself that death is a blessed relief. He then feels free to make his exit like a great actor performing the role of indignation.

Will the human male ever reach maturity?

Most scientists agree that adolescence is the period of life between biological and social maturity.

What does social maturity mean? What is the meaning of the other maturities that an adolescent likes to flatter himself with, as for instance, legal maturity, political maturity, or moral maturity? What is the meaning of expressions such as sentimental maturity, emotional maturity, academic maturity, or professional maturity? These are all nothing but abstract terms invented by man for specific, abstract reasons, for his needs of the moment. The meaning given to these expressions has changed and will continue to change throughout history, whenever there is a new gang in power.

In my view, a logical definition of adolescence might be the period between biological and mental maturity. Man is a mental animal, and without mental maturity he can not be considered an adult being. As far as the human male's mental maturity is concerned, the history of mankind, dominated by man, is clear evidence that man has not yet achieved it. A being living in a transcendental world can only pose as mature in abstract terms.

Man never advances beyond adolescence because adolescence provides the excitement of extremes. Adolescence is the first mental stage of man in which, as in any first stage, extremes dominate. Extremes give adolescents the impression of living life to the full. Adolescence is either noble or ignoble, but seldom understanding; selfish or charitable, but seldom reasonable; loving or persecuting, but seldom tolerant; cruel or pitying, but seldom indulgent; brilliant or stupid, but seldom wise; good or evil, but seldom fair.

Not only has man never advanced beyond the adolescent phase, but we will now see that whenever he feels that his mind has failed him, he reverts to infancy, a new, a man-made infancy; yet another creation of the human mind.

Index

| Parent Index

| Build Freedom:

Archive

Disclaimer

- Copyright

- Contact

Online:

buildfreedom.org

| terrorcrat.com

/ terroristbureaucrat.com