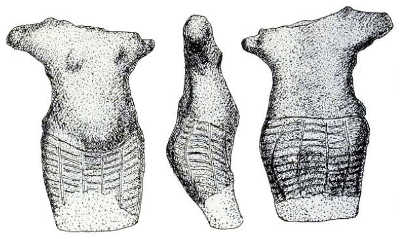

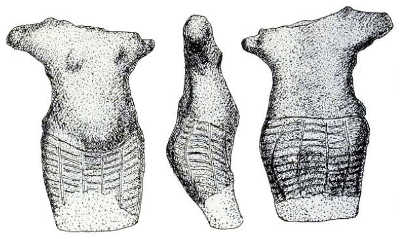

"Figurines of women were no longer naked but clothed."

With the success of the adolescent revolution, the human male took over the human groups. He faced a great problem which is still with us today: the problem of the organization of life. The long-established pattern of life based on the natural mother-infant relationship was broken, and man had to introduce a new one.

But what organization is a being with no instinct or innate pattern of behavior capable of producing?

Faced with this problem, the human male resorted to his mind, that mind which had helped him in his rebellion.

Abstract ideas, prejudices, and ideals were substituted for natural relationships. Later, political, social, religious, and economic ideologies and beliefs took over.

The mind's main difficulty was how to divide the work between the members of the group, the work on which the survival of individuals and collectivity depended. Previously a natural division of labor had existed, based on the mother-infant relationship. With the adolescent revolution, this production-distribution relationship was severed. For the conceited adolescent human male, work was degrading. It was a chore and therefore a punishment. Even today man finds work a sacrifice or a punishment unless it is a hobby or a job in the position of incompetence, which thereby flatters his ego. This self-infatuated adolescent needed a reason to work.

The only way the human male could solve this problem was with his new toy, his mind.

One of man's first abstract thoughts must have been death.

When man realized that he was mortal, he panicked. This sudden realization was the price he had to pay for his mind. He was terrified of his end. Playing with his mind, man tried desperately to overcome this fear. The scar left on the human old brain by the original rebellion gave the human mind the ability to see the other extreme, the antithesis. The idea of death inspired the idea of no death: the idea of eternal life, the idea of immortality.

The human male's pattern of life started by being dictated by immortality. Afterlife governed present life. Man began to organize and even to sacrifice his earthly life to deserve the afterlife invented by his mind.

How did the human brain reconcile eternity with the positive disappearance of life?

The idea of immortality was elaborated by analogy to the regeneration of plants through fallen seeds. The dead human body became the seed, through which new life must appear. The human body or the human head, like the seed, was covered to give growth to a new life.

When humanity realized that nothing grew from a planted corpse, the idea of immortality created the idea of the Underworld. Man convinced himself that there must be another world under the earth where the dead continued to live ad infinitum. This idea created the idea of tombs.

Human imagination invented all kinds of Elysian fields, and Hades: heaven for the blessed and hell for the damned. In Virgil's Aeneid, Sibyl explained to Aeneas that at one point "where the road splits in twain," in the Underworld, "the right road leads to the giant walls of Dis, our way to Elysium; but the left wreaks doom on sinners, and the guilty Tartarus sends."

Rewards and punishments in the afterlife had to be invented to assist man's idea of heaven and hell. These were connected with the idea of judgment.

Who was the judge?

The judge was the god selected by the gang in power, whose criteria of punishment were invented by the gang in accordance with its earthly needs.

How did humanity attain the idea of paradise and of hell?

I have already said that however omnipotent the human mind may be, it cannot create ex nihilo. I have also stressed that the mind's creations are programed by the scars left on the human old brain by the experiences of the human species. The idea of paradise must have been inspired by life in the woodlands; the idea of hell by life in the savannah.

The myth of paradise and hell are as old as the human mind's ability to create abstract thoughts. The Sumerians likened Paradise to their ancestors' life in the woodlands, but they saw hell as a sandy, dusty desert, like the savannah.

To Homer, the Elysian plain was "at the end of the world" where "men lead an easier life than anywhere else in the world." Through the mouth of Odysseus' mother, Homer described "the house of Hades and dread Proserpine," as this "abode of darkness" where the damned "perish in the fierceness of consuming fire as soon as life has left the body."

Virgil describes Elysium as "the happy region and green pleasantness of the blest woodlands, the abode of joy," the Tartarus as a place surrounded by "a fierce torrent of billowy fire." The savannah's intense heat, which left a deep scar on the human old brain, has inspired the idea of hell as a permanent fire throughout history. "That hell," wrote St. Augustine, "which is also called a lake of fire, will torment the bodies of the damned."

With the development of intelligence, however, and the realization that bodies putrefied in tombs, human wishful-thinking invented the soul. The soul became immortal. Man's flesh may die, but his soul will live forever.

Herodotus informs us that "The Egyptians were the first to hold the opinion that the soul of man was immortal."

In Plato's Phaedo, Socrates explained that when the soul liberates itself from the body it "departs to the invisible world - to the divine and immortal and rational." To Aristotle the soul is "the principle of life in living things." Aquinas stressed that "the human soul which is called the intellect or mind, is something incorporeal and subsistent." To Kant, summum bonum, blissfulness, is "only possible practically on the supposition of the immortality of the soul." To Kant, immortality was a moral necessity, it had to exist; it had to exist because human capriciousness imposed it.

Human beings were ready to risk anything to become immortal. Such was the fear, not of the actual death, but that with death there was nothingness. To disappear into nothingness was a terrible outrage, a deep humiliation for self-infatuated human beings. Leaving behind them a name which shall be eternal," is the supreme aim of man, according to Plato in his Symposium . . . "The mortal nature is seeking as far as is possible to be everlasting and immortal. . . ."

When in doubt of an abstract answer about immortality, the mind found that there was only one eventual possible solution: procreation. The one hope left to men was the hope that they would be remembered through their progeny, the hope that the offspring "will preserve their memory and give them the blessedness and immortality which they desire in the future," Plato wrote in the same work. Men "are stirred by the love of an immortality or fame."

In this obsession for immortality we see the reason why man imposed his name on his wife and children. Seneca criticized this human obsession. "The most fatuous thing in the world," he said, "is to marry to have children so that our name is not lost, or so that we have support in our old age, or certain inheritors."

Before he became self-conscious, man's procreation was caused by an obsession with sex. When man became self-conscious, procreation was assured by his obsession of immortality.

Throughout history, the most popular deities have always been those who were resuscitated after death, such as Tammuz, Osiris, Adonis, Attis, Persephone, Balder, and Christ.

In their search for immortality humans invented busts, portraits and self-portraits. It was not the love of art which forced popes, emperors, and kings to order their own portraits; it was one of their ways of remaining with posterity.

Someone rightly pointed out that to scientists, the Nobel Prize or immortality are more important than mankind. I would like to add that this does not only apply to scientists.

Here I quote a passage from an ancient Egyptian text, known as In Praise of Learned Scribes. "Be a scribe, desire that your name may last. A book is more effective than a decorated tombstone. . . . A man is perished, his corpse is dust, all his relatives are dead. It is his writing that makes him remembered in the mouth of the reader."

I also quote two sentences from this century of G. Le Bon from his Aphorismes du temps présent, in order to illustrate that the human obsession with immortality is eternal. "L'homme, confiné par la nature dans Péphèmere, rêve d'êternité. En élevant des temples et des statues, il se donne illusion de créer des choses qu'on ne verra pas périr."

The human obsession for giving anything, even life, for immortality, led Freud into committing an error when he stressed that humans possess the instinct of death. Men are indeed ready to risk their life for immortality. But this readiness to die is not caused by instinct, but by the idea of immortality created by the mind.

Man's self-awareness created in his mind the idea of existence. The origin of the word "existence" comes from the Latin existere. This is composed of ex and sistere meaning to cause, to stand, to step forward, to move upward from an inferior to a superior position, i.e.: from mortality to immortality.

I would like to analyze the efforts of man's mind in his search for a new pattern of life by describing the first civilizations. Anywhere in the world, the first pattern of life, after men discovered the mind, was inspired by the idea of immortality, the idea of a life after death.

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com