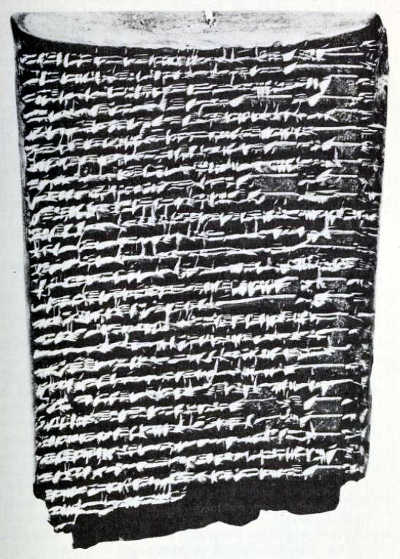

"Enuma-Elish, the Sumero-Akkadian epic of creation . . ."

The success of advancement of the adolescent revolution varied from peoples to peoples.

Definite evidence of the adolescent revolution can be found among cultural remains in the Balkans, in the so-called Old European Civilization, which flourished in the period between 7000 and 3000 B.C.

Judging by the shrines and figurines found in the Vinĉa Starĉevo and Cucuteni areas belonging to the period of the seventh, sixth, and fifth millennia B.C., religious life was governed by the Great Goddess. This must mean that human groups were still ruled by the mother figure and that society was based on a mother-child relationship.

By the end of the fifth millennium B.C., particularly in the Vinĉa area, central Serbia and the Sesklo area in northern Greece, figurines of male nudes proudly holding their penises were already in evidence. Another change took place in the same period. Figurines of women were no longer naked but clothed.

In Minoan Crete there was the Mother-Goddess culture and civilization. Women's high position in ancient Crete can be deduced from the artistic remains found in Knossos.

Except for two intermediate periods and for the reign of King Akhenaton, ancient Egypt remained dominated by women, until her end. The two main gods of ancient Egypt, Osiris, god of the underworld, and Horus, the living god, personified in the Pharaoh, owe their positions, the former his immortality, the latter his life, to Isis, the wife of Osiris and the mother of Horus.

There is historical and literary evidence that in China during the Shang dynasty (1766-1123 B.C.) and during the Chou dynasty (1123-256 B.C.), life was influenced by "The Divine Woman" (Shen nii). In China Shamanka (or mother) also had the important role of the oracles which can be seen influencing life even during the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-906). "The earliest available evidence shows that in the society of the Chinese bronze age, the Shamanka played a highly important spiritual role," we read in The Divine Woman (by E. H. Schafer).

The first historical evidence of a successful adolescent revolution was in Mesopotamia.

"My wife is at the outdoor shrine, my mother is down by the river and here am I dying of hunger." This early Sumerian saying illustrates man's arrogance, and pretentiousness, but at the same time dependence on woman in Mesopotamian society at the dawn of its history. The following Akkadian proverb shows man's successful liberation from woman's domination: "A woman without a husband is like a field without cultivation."

Enuma-Elish, the Sumero-Akkadian epic of creation, explains the victory of the adolescent gang against the domineering mother. In this epic the young gods chose the god Marduk as their leader to fight Tiamat, the mother of the gods. Tiamat was depicted as a monster dominating the chaos. Marduk kills her, taking from her "tablets of fate," the symbols of power. Then from her dead body he created the universe. Marduk also kills Kingu her husband, "and from his blood creates mankind. . . ."

The adolescent revolution in Mesopotamia changed the basic relationship between man and woman. In the name of his newly discovered strength, man started to force woman, chosen by him, to be faithful only to him. One of the main aims of man's positive legislation, from the first Mesopotamian laws until modern legislation, was to prevent woman from deriding man's self-infatuation and his belief in his superiority, by preventing woman's promiscuity and her economic independence.

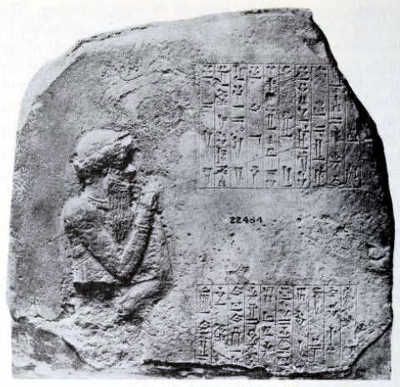

In the first known human laws, those of the Sumerian king, Ur-Namu, around the year 2050 B.C., we read: "If the wife of a man, by employing her charms, followed another man, and slept with him, the woman shall be put to death, the man going free."

In the Hammurabi laws of the eighteenth century B.C., unless the husband pardoned his wife caught committing adultery, she was burned.

In Assyrian society women sank to a pathetic and even ridiculous position. "If a woman has crushed a man's testicles in a brawl," says an Assyrian law, "They shall cut off one of her fingers, and if the other testicle has become infected . . . or she has crushed the other testicle in a brawl, they shall gouge out both her eyes." In Assyrian law there was capital punishment for a wife accused of stealing her husband's goods, and his goods even included her own dowry. An Assyrian man was allowed to beat his wife, and even to mutilate her body if he felt so inclined. He was free to divorce her whenever he pleased; the position of her finances were left to him. This situation is illustrated in the following legal rule: "If a man wishes to divorce his wife, if it is his will, he may give her something; if it is not his will he need not give her anything; she shall go forth empty."

Such laws show the vulnerability of man in power. He used his physical, political, economic, and legal strength to impose himself on woman. Man wanted to humiliate woman. He was terrified of being humiliated by her. Man is the only creature in nature who can be humiliated, the only animal who is self-infatuated.

There were two ways in which man could be humiliated by woman. One was her promiscuity, the other her independence. In Hammurabi's code, we read that a man could repudiate his wife without returning her dowry if she "engages in business, thus neglecting her house and humiliating her husband."

Mesopotamian civilization offers a clear picture of the struggle of the human mind in search of a way of organizing life, a struggle which was repeated in other civilizations at other times.

The Sumerian belief in immortality, in life after death, created the idea of tombs where the Mesopotamians buried food, jewels and working tools with their dead. Historical evidence for this was found in the Sumerian tombs of the fourth millennium B.C.

In the third millennium B.C., however, the Sumerian mind started doubting the concept of immortality. In the Sumero-Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, the King of Uruk, the hero of this popular epic, after a series of vicissitudes, finally obtained the magical plant of eternity from the gods but, alas, a serpent stole it from him, a great disappointment for the Sumerian adolescent mind.

In the following section of this pessimistic epic we can find this message: "For when the gods created man, they let death be his share and life withheld in their own hands."

What then was the purpose of human life? Why did the gods create man?

The epic explains that the gods created man to serve them; to slave for them. Work is for slaves, and therefore it is a punishment. By syllogistic reasoning this belief entertained the belief that whoever had slaves were gods. Serving the gods meant in practical terms slaving for the inventors of gods, who were the gang dominating the temple of the city's god. The chief priest of the temple soon became the king of the city, and judging by the "Sumerian King List" which, although from the beginning of the second millennium B.C. must have reflected the traditions of centuries long past, the powers of kings "descended from heaven."

The exploitation of believers is revealed in the following lines from the Mesopotamian Dialogues of Pessimism: "They walk on a lucky path who do not seek a god, those "who devoutly pray. . . become poor and weak."

There is little difference between these ancient words on the exploitation of beliefs to the following modern anecdote. A Chinese reproached an American, saying, "In your country man exploits man." When the American asked, "What about your country?" the Chinese answered, "In my country it is the other way around!"

Something else can be deduced from the Epic of Gilgamesh. It is revealed that the gods also needed man to work in order to maintain the divine order.

What was this divine order?

It was the opposite of chaos. But what was this chaos so feared by man?

To the adolescent mind, chaos meant a life of promiscuity, a life dominated by women. In the Sumerian creative myth Emuma-Elish, the mother goddess, Tiamat (who was killed by Marduk), represented chaos. To the male adolescent the divine order was an order in which he was the center of the universe. That may be the reason why humans took so long to produce a Copernicus.

Increasing doubts about the idea of immorality increased dissatisfaction over the organization of a life based on the belief in an afterlife. This created an atmosphere which is reflected in the text The Pessimistic Dialogue Between Master and Servant, particularly in the following passage:

"Servant obey me!"

"Yes, my lord, yes."

"I will do something helpful for my country."

"Do, my lord, do. The man who does something helpful for his country, his deed is placed in the bowl of Marduk."

"No, my servant, I will not do something helpful for my country."

"Do it not, my lord, do it not. Climb the mounds of ancient ruins and walk about: look at the skulls of late and early men: who among them is an evil-doer, who a public benefactor?"

How did the Mesopotamians solve the problem of the failure of their mind?

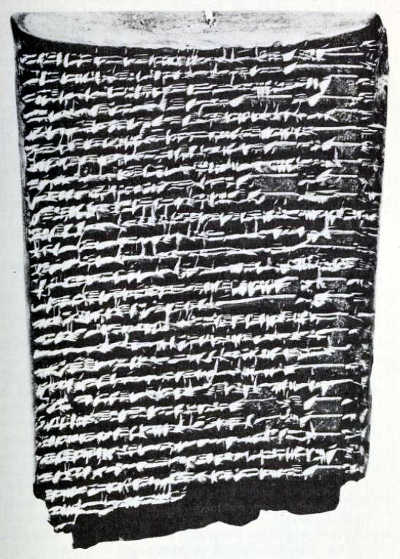

The human mind found three solutions to solve the problem of gloom and despair caused by its failure to find a solution to the male-organized way of life. These three solutions were Mesopotamia's legacies to mankind: alcoholism, divination, and a pattern of life imposed by codified laws, enforced in the name of an omnipotent and monotheistic God.

The significance of alcoholism (which is derived from a Sumerian word) can be gained by the following verses from a Sumerian hymn:

Drinking beer in blissful mood,

Drinking liquor, feeling exhilarated.

The heart of Inanna is happy again,

The heart of the Queen of Heaven is happy again.

In a passage from Enuma-Elish, we find how the Sumerian deities used alcohol:

They smacked their tongues and sat down to feast

They ate and drank,

Sweet drink dispelled their fears,

They sang for joy drinking strong wine

Carefree they grew, their hearts elated.

Here we can understand how the "sweet drink dispelled" even the fears of the mighty gods. For the human mind, alcohol is a necessity. No animal needs alcohol.

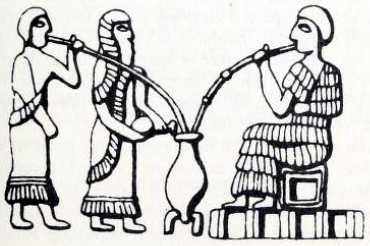

The mind's second solution to the problems of life was divination. Astrology was born in Mesopotamia and the reading of animal's lungs, liver, and intestines was born before the invention of writing. The importance of divination in the life of ancient Mesopotamia can be seen in the text The Lord of Wisdom.

The third solution to the crisis of the Mesopotamian mind was its main legacy to mankind.

We know that man regressed to infancy when faced with any crisis or despair. Regressing to infancy means going back to gremio matris, to the maternal way of life. For the self-infatuated male to go back to his mother, especially in the early stages of his rebellion, would have meant humiliation.

What then could the solution of the Sumerian mind have been, lost in a mental savannah?

The solution was a new invention of the mind, an abstract infancy, a man-made neoteny. The mind invented a father, a strong, omnipotent, and omnipresent father. The Mesopotamian male regressed to an abstract infancy, protected by an abstract father. In that infancy he begged his father to direct him in his life, offering him the only thing a confused mind can offer, obedience. The father, the absolute ruler, the omnipotent god, is the creation of a mind which has failed. An unsuccessful mind is always prepared to obey.

What caused this desire to obey?

It was brought about by a desire for orders, orders which suited the mind. Eagerness to obey orders inspired orders. The human mind's creation "ought to be" inspired human obedience, thus creating authority, power or might in the hands of a god or a ruler, a church or a state. This transformed "ought to be" into "thou shalt." Omnipotent dictatorial gods or rulers were, and will always be, victims of their followers.

Man, who rebelled against his mother in the name of autonomy and freedom, after various exploits of his mind, reverted to obedience, the childlike obedience to a father, an invented might. Man will always be an unself-sufficient and dependent creature.

This example of the Mesopotamians regressing to an abstract man-made infancy will be repeated throughout history. These periods of infancy will occasionally be broken by adolescent revolutions which, after a spell of the adolescent male-rule of competition, strife, and anarchy, will result in a new phase of abstract infancy with a new god or ruler, a new father figure, a new might. This will be followed by a new adolescent revolution, and so on.

Once an abstract infancy is re-established in a human group, the individuals who do not regress to infancy, those who refuse to conform to it, those who remain in the adolescent phase, will be considered, throughout historv, as sinners, heretics, and outlaws. All criminals, revolutionaries, and heretics, of all ages, were, are, and always will be the adolescents in a society of man-made infancy.

It is interesting to note that generally, in these periods of man-made infancy, playing is often forbidden, and games require permission from the authorities. With the advent of Christianity, Emperor Theodosius ended the Olympic Games.

The Mesopotamian people, unable to create a convincing myth about the afterlife through which they could organize their life on earth, created positive laws instead. These laws were inspired and enforced by the earthly authorities in the name of a powerful god.

Codes of law are always created by an absolute ruler or an omnipotent god, in times of confusion of past beliefs, in a moment of capitulation by the adolescent mind, a moment of reversion to paternal infancy.

Judging by the first codified laws which appeared in the middle of the twenty-first century B.C., the laws of Ur-Nammu, and of Hammurabi's laws in eighteenth century B.C., Marduk was clearly the omnipotent, omnipresent and sole god of Babylonia, taking over from Anu and Enlil, the previous great deities of the Mesopotamian Pantheon. He was called Bel, which means the supreme of all supremes. We read this in the seventh tablet of the Epic of Creation:

God Enlil: it is Marduk of government;

God Nabu: it is Marduk of opulence;

God Ninurta: it is Marduk of works;

God Sin: it is Marduk who illuminates night;

God Adad: it is Marduk of rain;

God Nergal: it is Marduk of war;

God Zabala: it is Marduk of battle;

God Shamash: it is Marduk of justice.

In the prologue of Hammurabi's code of laws we read: "Anu and Enlil had endowed Marduk with the supreme power for whom they founded the eternal kingdom in Babylon. . . ."

Why did Marduk become "the strongest of all gods"? The adolescent male, confused in his mind, worshiped strength in his leaders and in his gods. Strength inspired confidence. A confused mind craves confidence.

Marduk was better-armed than any other god. In the Sumero-Akkadian Epic of Creation, when Marduk, as a leader of a "horde of young gods" goes into battle against the mother goddess, he is armed with a bow and arrow, a streak of lightning . . . a bolt of thunder and seven winds, and riding a chariot of storm drawn by winged dragons breathing fire.

"Your name is the greatest, O ferocious Marduk," we read in a hymn. He is "King of all Gods and of all Kings."

The most important Babylonian festivity, Akitu, shows us Marduk's omnipotence. Akitu was the name given to the New Year celebrations which lasted for twelve days. On the eighth day the king and his dignitaries went to the tower of Babel, in the famous chapel of Marduk, where the "supreme of supreme gods" gave the king of Babylon the orders and predictions for the coming year. Called "The Settling of Destinies," this ceremony was considered the main event of the Akitu festivities. Marduk, the absolute god, reinvested the king of Babylon with absolute power. Religious monotheism and temporal absolutism helped each other throughout the history of male-organized societies. Only a strong god, only a god without competition with other gods, is able to bestow equality on the confused adolescent mind afraid that, through competition, the strong could do better than the weak.

"Mankind, tired out with a life of brute force" . . . "submitted of its own free will to laws and stringent codes." These words of Lucretius, echoed by Rousseau and hundreds of authors and politicians, express a certain truth. They do not explain, however, that the "life of brute force" came with the adolescent revolution, male competitiveness and competition, antagonism, arrogance, and aggression, caused by self-infatuation, the creation of the mind. The human mind, having embraced confusion, its own cul-de-sac, had no alternative but "laws and stringent codes" as the solution to a male pattern of life.

Marduk, in the end, being without competition, was so strong that he was even capable of compassion. In the text of Lord of Wisdom, we read that he is the god "whose heart is merciful, whose mind forgiving, whose gentle hand sustains the dying." "The strongest of all gods and all kings," the omnipotent Marduk, "this merciful god," was the terminal outcome of the first adolescent revolution in Mesopotamia.

After centuries of vicissitudes and searching for a pattern of life, the minds of the Mesopotamian people solved their delusions by regressing to infancy, an infancy created by the same mind, an infancy protected by an idealized father, a father created by wishful thinking, the wishful thinking of the masses. The delusions created the masses who were ready to revert to a father protected infancy.

This idealized father is flattered by the people's worship and obedience. Flatterers will get what they want out of the flattered father. A flattered father is blind, easy to fool, easily led, led by obedience, the instrument by which the masses achieve their aspirations. Obedience is never blind. Obeyed gods and leaders are blind.

The Mesopotamian pattern was repeated throughout history until the time of the modern gods, gods led, used, and abused by the masses, who are only the capricious and spoiled children of a powerful but blind father.

We have seen that in Babylon, Shamash, god of justice was "Marduk of justice." Justice was therefore in the hands of Marduk which he bestowed upon his king on earth each year. We read the following in the introduction of the Hammurabi's code of laws: "I am the king who is pre-eminent among kings: my words are choice, my ability has no equal. By the order of Shamash, the geat judge of heaven and earth, may my justice prevail in the land" . . . "By the word of Marduk, my lord, may my statutes have no one to rescind them!"

What was justice, invented by the human mind?

Before the adolescent revolution there was the mother-infant relationship, based on equity, maternal equity, meaning unequal treatment of unequals. The maternal organization of humanity was based on this principle for more than 16 million years.

With the adolescent revolution man rebelled against this equity. The adolescent revolution introduced adolescent justice, which was expediency, the expediency of the strong. The strong became right. It was in this state of anarchy that human justice, as we know it today; was born. Human justice became another peculiarity of man. Human justice, in essence, is a pleonasm, because justice is always human, it is always created by man's mind.

There is no justice in nature, only laws.

The first and the supreme purpose of justice was to prevent the strong from abusing the weak. The first idea of justice, which in essence is in conflict with the primary law of nature, the right of the fittest to survive at the expense of the weak for the sake of the species, must have been inspired by the deep scar left on the human old brain when the humans were expelled from their natural environment by the stronger apes.

The old scar may have been revived by the majority of the weak, by the dramatic experience of the first adolescent revolution.

But who, in the human groups dominated by adolescents, was able to prevent the strong from imposing their strength over the less fit?

The strongest might! It was might, from which the church and the state emerged, that could stop the strong from overrunning the weak. Who represented might in the human groups? The person who commanded the most obedience among the group, whoever could have given the commands inspired by the wishes of the majority and its readiness to obey. The obedience of the majority in a group dictates its justice and imposes it on the strong. The weak, always the majority in any human group, create might. Might and the weak will always be allies against the strong. Might is right because only might can make right, restore broken harmony, do justice, make reparation. Above all, might can vindicate the weak.

In a Mesopotamian document it says that Ur-Nammu, "established justice in the lands and banished malediction, violence and strife." The purpose of Hammurabi's code of laws was "To cause justice to prevail in the land. . . ." What was the purpose of his justice?

"The purpose of justice is to destroy wicked and evil, that the strong may not oppress the weak. . . ." the text explains.

Abusing the weak was punished in the name of equality, an equality determined by the weak. Equality imposed impartiality on justice.

The aim of man's justice was to prevent injustice, to prevent inequality, to prevent natural laws. Human justice is the invention of a loser or a potential loser. Losers are always the majority. Man's justice is not creative or rewarding in the natural sense; on the contrary.

Man's justice, aiming at preventing injustice and inequality by the punishment of the unjust and of the inequal, uses a simple arithmetical and proportional method, called by the Romans jus talionis, a law of retaliation: "an eye for an eye - a tooth for a tooth."

Later, the weak invented so-called "social justice" too. This was inspired mainly by equality in the economic sense, the elimination of visible economic differences. Man knows that social justice in the distribution of wealth seriously prejudices his working productivity, the production of wealth. For man in his abstract infancy, however, economic equality was more important than his economic welfare or his own survival, or that of his progeny or his species.

What was crime?

Crime was anything that broke the harmony and peace created by the tacit or written agreement between the weak and might. In the Sumero-Akkadian Epic of Creation the husband of the great mother goddess wanted to destroy the young gods in the name of justice. We read: "Their manners revolt me, day and night without remission we suffer. My will is to destroy them, all of their kind; we shall have peace at last, and we will sleep again."

Aquinas later stated that "Peace is the work of justice indirectly, in so far as justice removes the obstacles to peace. . . ."

A series of crimes considered by the first legislators can be seen in a Sumerian hymn which goes:

Hypocrisy, distortion,

Abuse, malice, unseemliness,

Insolence, enmity oppression,

Envy, force, libellous speech,

Arrogance. . . breach of contract,

Abuse of legal verdict,

All these evils the land does not tolerate.

All these are characteristics of the adolescent male, and are feared by the weak who have entered an abstract infancy protected by a mighty father - by a church or by a state.

What is punishment? Why should men punish other men?

This subject has interested humanity from Aristotle, Plato, and Protagoras to Kant, Hegel, and Freud, from Aquinas and Dante to Cesare Beccaria, Bentham, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, and from the Bible to Karl Marx. In the Old Testament punishment was the right to retaliate. To Aquinas, "the order of justice belongs to the order of the Universe and this requires that penalty should be dealt out to sinners." To Hobbes "intemperance is naturally punished with diseases" and "injustice with the violence of enemies." To Kant "Juridical punishment can never merely be administered as a means for promoting another good. . ." "but must in all cases be imposed only because the individual on whom it is inflicted has committed a crime." To Montesquieu, the only reason for punishment was to prevent crime. To Mill, punishment was nothing but "a natural feeling of retaliation or vengeance." In classical Greece punishment was an expediency. In Thucydides we read of Diodotus' protest over the Athenian decision to put the Mitylenians to death. "We are not in a court of justice, but in a political assembly," he stressed, "and the question is not justice but how to make the Mitylenians useful to Athens." According to Freud, humans crave punishment: "The unconscious need for punishment plays a part in every neurotic disease."

Human justice was born from the chaos created during the adolescent revolution. Any adolescent not conforming to the contract between the weak and might was a criminal, a sinner, or a heretic. Only adolescents could be criminals, sinners, or heretics. This implies that no one can be a born criminal, a sinner, or a heretic. It also implies that only man commits crimes, sins, or heresies; a woman seldom does; she does not possess an adolescent mind. A woman can only commit crimes, offenses, or heresies by imitating man, forced by man, or to please man.

What is the purpose of punishment then in a society of abstract infancy?

The purpose of punishment is to correct the criminal or sinner or to convert the heretic. The weak, the masses of any society, the ones who dictate the law of the land, either fear abnormalities or are jealous of them. In either case the weak ask might to eliminate the abnormal, which disturbs the social harmony and above all spoils their peace of mind.

How is this elimination of disturbing abnormalities carried out?

By the physical elimination of criminals, i.e. murder; by getting them out of sight, i.e. expulsion; or by correction.

How are abnormal people corrected or converted?

Abnormal people, such as criminals, sinners, and heretics were, and still are, knocked off their pedestals of adolescent self-infatuation and forced to join the level of the established infancy. This is done by fear, by modern savannahs such as Siberia, but above all by torture and the infliction of physical or moral pain. The aim of this is to humiliate the adolescent, to shake his self-infatuation and his self-confidence.

For man, any physical or moral pain, inflicted as punishment, hurts because it degrades. Man bears great pain without complaint if it is a biological, moral, or aesthetic service. He cries, however, when punished, not so much because it hurts but because it damages his self-infatuation, because it lowers the self-esteem created by his mind. That is why man is more frightened of pain than woman. A woman does not feel degraded by pain: she is seldom in a supernatural state.

In some adolescents, punishment produces pathological consequences, such as regression to very early infancy. This is known as Psychosis Poenalis. The prisoners behave like small infants, often wanting to be spoon-fed, wetting their beds, and even developing stammers and lisps.

As the first purpose of punishment is to correct the criminal or convert the heretic by making him revert to infancy, it is obvious that it would not succeed with a woman. A mother, or a potential mother, could not revert to infancy. Equality of punishment for equal crimes for men and women therefore was, and still is, a great mistake. Punishment for women can only succeed as a deterrent, never as a corrective.

The same punishment for criminals of different ages is also a mistake. Corrective punishment for a child is useless. It cannot make him revert to infancy, he is already there.

There has never been a plausible explanation of jus talionis. Why "an eye for an eye" justice?

As I have said, criminals are adolescents - arrogant and aggressive adolescents. How do adolescents externalize their aggression or arrogance? By attitudes or actions that they consider the best way of affirming their superiority.

When the arrogant, aggressive adolescent, by committing a particular crime, found the superiority that he was searching for, the first judge felt that the best way to destroy this superiority, and to demote him to infancy, was by hitting him in the very spot that he had used to achieve his superiority, by hurting him where he had hurt. The first judge knew the true meaning of adolescence. He started his job at the peak of the chaos created by the first adolescent revolution.

The Roman idea of punishing a crime committed with dolus, evil intent, more severely than an identical crime committed with culpa, negligence, contributes to our explanation of the nature of punishment.

The second purpose of punishment was the prevention of crime - bv a deterrent. This is evidence of the sadness of the male organization of life, of the mockery of man's so-called achievements. The only guideline to human behavior that the human male was capable of achieving, was the threat of punishment.

The third purpose of punishment was to give pleasure, orgasmic pleasure to the mediocre, who are only too delighted to watch someone whom they have always been secretly jealous of punished and humiliated.

In cases of excessive adolescent characteristics, punishment fails to succeed as a corrective. These individuals are known as "recidivists" in legal terminology, and "the neurotics" by Freud, who claimed they craved punishment. In my view, the explanation is simpler. Punishment can never succeed as a corrective with individuals with strong adolescent characteristics. Strong adolescents despise the mediocre, their justice and their punishment. This contempt gives them a feeling of superiority and an insensitivity to their pain. Legislators and psychiatrists should look for something else to replace punishment and electric shock treatment, as instruments of correction, in cases of individuals with strong adolescent characteristics. Electric shock is not a treatment, but a punishment. Like any punishment, its purpose is to bring the individual to the savannah, to primordial atavistic fear, to infancy.

Some humans, unhappy in adolescence and in the father-protected infancy, try to find their own way back to the savannah by self-inflicted punishments such as alcohol, drugs, and gambling.

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com