"The dialogue between Achilles and Hector illustrates the boyish mentality of Homer's heroes."

"The gods of Homer's pantheon were anthropomorphic gods, humans' playmates."

"The gods of Homer's pantheon were anthropomorphic gods, humans' playmates."

Ancient Greece offers us the clearest picture of the adolescent revolution. The history of ancient Greece is also important, because no other country, either before or since, has dedicated such mental energy to finding a pattern of life.

When the ancient Greeks entered mythology and history they were in their pre-adolescent phase. Male humanity in this phase is best described in the Iliad and the Odyssey. It is a phase in which male humanity and the male deities play and explore exuberantly in open spaces returning, however, sooner or later to their women.

Homer's characters invoke the mother's help with every problem they face. When Achilles realized that Agamemnon had taken Briseis, his slave girl, he cried: "'Mother, you bore me doomed to live but for a little season: . . . Agamemnon, son of Atreus, has done me dishonour, and has robbed me of my prize by force.' He wept aloud as he spoke. . . and his mother heard him and said: 'My son, why are you weeping? What is it that grieves you? Keep it not from me but tell me, that we may know it together.' " This was the behavior of Achilles, the strongest of all men.

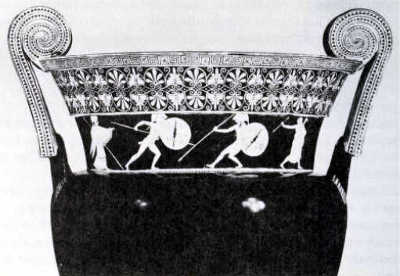

The dialogue between Achilles and Hector illustrates the boyish mentality of Homer's heroes.

"Come nearer so that sooner you may reach your appointed destruction." To these words of Achilles, Hector answers: "Son of Peleus, never hope by words to frighten me. As if I were a baby. I myself understand well enough how to speak in vituperation and how to make insults."

Play was the essence of the entire Trojan War. At one point, while keeping Helen, Paris proposed to return all the stolen treasures, adding even some of his own, to end the war. The Greeks rejected the offer. The war was a case of bad humor over a toy, a bad humor which prolonged the show and the adventures. Helen was the toy. Paris risked the life of Troy and the Trojans for her. We must not forget that at this stage love did not exist.

In the world of Homer, nothing was tragic, not even death. Death merely caused a temporary sorrow, sorrow for having lost a playmate. Even the horses of Achilles were said to lose their playmate. This sorrow soon passed; there were no attachments in the stage of pre-adolescence. Transcendentality was, as yet underdeveloped.

The gods of Homer's pantheon were anthropomorphic gods, humans' playmates. In the Trojan War the gods too played at war, some helping one side, some another. They even played tricks on humans. Agamemnon complained that he was a victim of one of these tricks, when he took Achilles' mistress, Briseis, the slave girl. "Not I was the cause of this act," he claimed, "but Zeus, and my portion and the Erinyes who walks in darkness: They, it was, who in the assembly put wild ate (temptation) in my understanding, on that day when I arbitrarily took Achilles' prize from him." Like a child, he adds: "So what could I do? A deity will always have its own way." Agamemnon was sorry. He wanted to do anything to repair his error. "But since I was blinded by ate and Zeus took away my understanding, I am willing to make my peace and give abundant compensation," he said. Ate was a temptation, an example of bad humor, an impulsive action characteristic of pre-adolescence. In this case, Achilles' slave girl was merely the toy.

When these playful children in the Iliad force the play too far, and out of control, they blame menos, a diabolical spirit which is placed in their breast by some deity. Penelope, speaking of Helen, said: "Heaven put in her heart to do wrong, and she gave no thought to that wrong-doing, which has been the source of all our sorrows."

Zeus was even cross with humans because they accused the gods of their own errors. In the Odyssey he says that "men complain that their troubles come from us; whereas it is they who by their own wicked acts incur more trouble than they need." This sounds a little like children accusing each other over a broken window.

In the world of Homer, the dominating characters were the women. While male humanity and the gods played at war, Demeter, the goddess of agriculture worked in the fields. While Odysseus enjoyed adventures around the world, Penelope was working and running the household responsibly and patiently. In the thick of the chaos of the Trojan War, Andromache addressed Hector: "Dear husband, your valour will bring you to destruction; think on your infant son, and on my hapless self who ere long shall be your widow."

This early adolescence of Homer's male world, is best illustrated in Odysseus' adventure on the island of Ogygia. Calypso promised Odysseus that if he remained with her he would gain immortality. He refused this precious gift, preferring to go home in the end. He wanted to go back to Penelope. It is in the nature of a pre-adolescent to return home in the end. He is not an individual yet, but the member of a group, a female-dominated group. In order to become an individual an adolescent must cut his umbilical cord at the doors of his oikos, his household. The human male cannot become fully adolescent without killing his mother or destroying her domination. Oikos, this large household governed by women, in Homer's world, had to be destroyed in order for the male to attain full adolescence, replacing it with his father-dominated family. Agathos characteristics in Homer's times were nobility, solidity, patience, and hard work - the main characteristics of women.

To sum up the relationship between woman and man in the world of Homer, I quote from the penultimate verse of the Odyssey: "Thus spoke Athena, and Odysseus obeyed her gladly."

Other writers agree that the world of Homer was a world of shame-culture. Shame can only be inspired in male humanity by the mother or by the maternal organization of oikos.

The Iliad and the Odyssey are epics of space. The Homeric world was a wide-open world. Humanity influenced by women is cosmopolitan in its character.

When man discovered the power of the mind, he discovered agoraphobia. Agoraphobia must have inspired the idea of polis (city-state). Polis confined space. Sumerians, reaching their full adolescence, built their city-states. The Egyptians, who never achieved full adolescence, were more of a nation-state than a city-state.

My thesis that the higher a woman's position in society, the more honored is work, is confirmed by Homer's Greece. The Iliad and the Odyssey are filled with descriptions of both the gods and the people working. Work is described in minute detail, which would never have happened had it been a boring or humiliating activity. We read of Apollo building the wall of Troy; Hera, the wife of Zeus, dealing with his chariot and his mules herself and Paris happily building his own house. Odysseus talks proudly about his nuptial bed: "which I made with my very own hands" . . . "I built my room around this with strong walls of stone and a roof to cover them and I made the doors strong and well-fitting," he adds. Odysseus says to his father: "I see, sir, that you are an excellent gardener" . . . "I trust, however, that you will not be offended if I say that you take better care of your garden than of yourself."

I have stressed that Homer's society was a co-operative society. How did this co-operation work? What were the rules for the division of labor?

The answer to this can be gathered from a verse in the Odyssey: "My delight was in ships, fighting, javelins and arrows," explains Odysseus. "Things that most men shudder to think of; but one man likes one thing and another another, and this was what I was most naturally inclined to." The division of labor must therefore have followed the principle of "most natural inclination." This was the basis of co-operation and economic productivity in the world of Homer.

At about the beginning of the ninth century B.C., the Homeric world ceased to exist, opening the door to the Archaic period. This tumultuous period of Greek history was the transition of Greek male humanity from early adolescence to full adolescence.

With adolescence, the male in Greece faced the problem of the organization of life. The pattern of life in Greece, as with other adolescent revolutions, became the will of the leader of the gang. The gangs started separating from the mother-dominated communities, forming their typically adolescent creation, the polis, the city-state. The leader of each polis became the absolute ruler of the men and women whom he had succeeded to seduce, or force to follow him.

At the start of its formation, the polis must have been a small unit. By the end of the sixth century B.C., there were more than six hundred city-states in Greece, some of them still very small.

The leader of the gang became the king of the city-states, dividing the land of the new city-state between the most combative members of his gang. This was a major transition from the collective possession of land on which the female organization of the human groups was based, to the private ownership of land on which the male organization of the human groups started to be based. The collective possession of the female-dominated group was the land cultivated by the group. Private property was an invention of man's mind. Man transformed a temporary possession of land into a permanent one, by indicating his intention of keeping it, even if by his negligence it lay waste, and even if it gave the impression of being res mullius. (Later, Roman legislators called this desire to keep land in sole possession animus. This individual animus, added to corpus, transformed private possession into private property.) From the beginning of his adolescent revolution, man knew that his independence and his superiority needed something positive to lean on. He knew that innately he had nothing to make him either independent or superior. Private property is a creation of the adolescent male, a creation of his antagonism and competitiveness. The reason for "mine" was to oppose "thine." Land became inalienable, thus transforming the descendants of the members of the gang into the ruling class, the aristocracy. This aristocracy governed the city-states until the end of the seventh century B.C., until the appearance of the plutocrats, the people with money, money that could buy power by indebting the landowners or their heirs.

What was woman's position in this gang-type civilization?

In the world of Homer, man respected woman. The human male, in order to become an adolescent, has to free himself from his respect. The only way to free himself from his respect is to fight respectability and those inspiring it. Fight meant victory and victory meant enslaving the enemy. Woman became the slave of man. In that position he was less afraid of her mocking his conceit.

From a position of respect woman became the object of contempt. Even mythology changed. When Prometheus illegally gave man fire, Zeus, in order to compensate this advantage, gave man a "plague" to live with: "Damnable race of women." Furies or destructive natural forces became female. (Even today hurricanes are given female names.)

In his The Theogony, Hesiod relates a popular tale which marked the changing times. Metis, the goddess of Wisdom, was pregnant. Zeus, fearing that her unborn child would be greater than he, thereby becoming his substitute, swallowed her. She was the last deity of wisdom in the Greek Pantheon.

In the seventh century B.C., Semonides of Amorgos introduced malevolence, which became a Greek characteristic, in denigrating women. Semonides claimed that Zeus created the female brain from the brains of all sorts of animals.

The feminine characters that the Greek male mind invented, from Alcestis and Antigone to Clytemnestra, Medea and Phaedra, show, however, that Greek men never really liberated themselves from their fear of women.

This latent fear forced the ancient Greeks to extremes of adolescence, extremes never before or after achieved by anyone. In these extremes we see the reasons for Greek competitiveness, antagonism, egocentrism, disunity, philosophy, narcissism, and homosexuality.

What had happened to Homer's playful gods?

Adolescence is an age of tragic seriousness and purposefulness, an age which abhors play. Zeus, no longer a joyous, playful god, became the powerful father of the pantheon, inspiring the domineering father of Greek families.

Because of their extreme characteristics of adolescence, the Greeks even started fearing each other. They began to be victims of each other's competitiveness, antagonism, boasting and hubris. A poor or weak man was merely a victim of the stronger or more aggressive man, and it was inadvisable for the poor man to react. In the Works and Days of Hesiod, written in about 700 B.C., we read: . . . "for hubris is harmful to a poor man." This defenselessness against the stronger is illustrated in the same works of Hesiod by the following fairy tale, where the hawk is talking to his victim the nightingale: "Miserable creature, why do you lament? One who is far stronger than you has you in his grip, and you shall go wherever I take you, singer though you be; and I shall either make you my dinner or let you go as I choose. He is foolish who tries to resist the stronger, for he is bereft of victory and suffers woes in addition to disgrace."

What could the solution be for the victims of hubris?

Justice! Zeus became justice! He had to protect the weak and poor. Hesiod expressed the feeling of the masses when he stressed: "But for those who practice hubris and harsh deeds, Zeus. . . doles out a punishment. Often even a whole city suffers because of one man's wrong, and his presumptiveness."

In the human jungle, in which the stronger survived, Hesiod produced another wish of the masses: "For Zeus has established this law for men, that fishes, wild beasts and winged birds should eat one another, for they have not justice among them; to mankind, though, he gave justice, which proves to be much the most beneficial."

Success and fame became an obsession in any field and at any price, success, and fame in economy being the most important. Wealth, giving the best sense of security, became the supreme aim. Money-economy, which started then, helped unscrupulous adolescents in their aspirations. Money created debts, and debts created slaves and servants. This meant wealth and power. This can be deduced from the writings of Theognis of Megara who said: . . . "for the majority of people there is only one value - wealth."

The masses soon realized, however, that the justice of Zeus did not succeed. Hubris was producing success, fame, wealth, and the good life, at the expense of the weak. The masses found another consolation. Zeus may not punish the arrogant but he will punish their progeny.

Soon, however, some were not happy that god should punish the innocent progeny for their unjust ancestors. Theognis registered this feeling by saying: "that the wrongful deeds of the father should not bring harm to his children, and that the children of an unjust father, who were themselves just. . . should not pay for the transgression of their father. . . . As it is, the man who does wrong escapes, and another man pays for it after."

By the year 620 B.C., general confusion produced a dramatic reaction. The people began to accept the toughest human justice that had ever been, the justice of Draco. Most offenses received the death penalty. Plutarch rightly claimed that Draco "wrote his laws in blood."

The start of the sixth century B.C. brought Solon, a much wiser Athenian legislator. The aim of Solon's laws was to restrain "obsession for wealth," "restrain excess," and "establish order." What class of order? Solon answers "the old order." To understand the quest for "the old order" I must explain another phenomenon of adolescence.

Adolescence produces a permanent war between two generations, fathers and sons. The hubris of the new generation, their "obsession for wealth," could only go against the wealth of their fathers. Solon wanted the new generation to exercise moderation, to show respect for their fathers. His first aim was made clear in these lines from one of his poems: "I desire to possess wealth, but not to possess it unjustly; just punishment always comes afterwards; the wealth that the gods give remains with a man permanently . . . whereas the wealth that men pursue by hubris does not come in an orderly decent manner, but against its will, pursued by unjust deeds; and swiftly disaster is mingled with it. . . ."

Solon tried to reinforce this respect by changing the law of succession. He gave the father more freedom in making his will, even permitting him to emancipate his slaves; this was also done to make slaves more obedient and respectful.

With this move toward more respect for fathers, the story of Oedipus passed through a metamorphosis. Intended as an amusing misunderstanding, Oedipus was transformed into a tragedy dramatized by Sophocles. In the old version, Oedipus remained the King of Thebes until his glorious death and ceremonial burial.

Solon knew that divine justice could only work if it was helped by human justice. Only by helping Zeus with his positive laws could Solon claim, in his famous Eulogy, that Zeus, in spite of everything, was a just and fair god.

According to Plutarch, who wrote his life story, Solon, having seen the negative consequences of provisional times, fixed the duration of his laws for one hundred years. His aim was to reach a state of eunomia, a word interpreted as the "good laws," "good order," "just distribution," or the "obedience to laws." In my view, his aim was stability. He must have known that the main cause of hubris was instability.

In order to please or appease the Greek male adolescents, Solon expressed his contempt for woman in his legislation. Woman's influence was considered dangerous, therefore her juridical position was reduced even more, limiting her rights of property.

Woman's position declined continuously. Hesiod called her Kalon Kakon - a beautiful catastrophe. (Judging by Zorba the Greek, times in Greece have not changed.)

If my thesis that the higher the woman's position in society the more honored the work is true, work in Greece from the time of Homer must have deteriorated considerably. And in fact this was so. By the sixth century B.C., work was for slaves and servants.

In Hesiod's age work meant "inevitable evil." It was called panos. Some writers explain that from this word the Latin word poena emerged, meaning suffering.

The Archaic Age in Greek history ended with a desperate plea by the Greek Gnomic poets and didactic popular sayings, for sophrosyne.

Sophrosyne is one of those untranslatable Greek words which means "be reasonable" and "keep your intelligence clear of your mind, as the mind is the source of hubris." The following advice from Sophocles in Antigone explains the real meaning of sophrosyne. "For old anonymous wisdom has left us a saying: 'of a mind that god leads to destruction, the sign is this - that in the end its good is evil.' Not long shall that mind evade destruction."

"With the increased confusion of the second half of the sixth century B.C., the Greek mind opened a new path in the search for a pattern of life. Philosophy was born. The mind, through its abstract speculation, started groping for the truth, the basic, natural or cosmic truth on which to build a pattern of life. Greek adolescents, encouraged by this new infatuation, persuaded themselves that the human mind was able, through speculation, to find a rational explanation of life and therefore to close the dark chapter of mythology.

In their self-confidence and beginners' enthusiasm, the first philosophers took an extreme anti-mythological attitude. In Xenophanes of Colophon, we read the following: "Homer and Hesiod have ascribed to the gods all things that are a shame and a disgrace among men, thefts and adulteries, and the deception of each other." According to Heraclitus, "Homer should be turned out of the lists and whipped, and Archilochus likewise."

Philosophy did, however, make one major contribution to humanity. In its search for the primeval, philosophy opened the way to science. But this contribution could not compensate for the damage it has created throughout history, for philosophy always stoops sooner or later to some belief, and therefore to aggression.

One of the first philosophers was Pythagoras. His speculations may have helped him to discover important mathematical laws, but as far as the general principle of life was concerned, his philosophy resulted in belief, a belief of the transmigration of souls. A similar belief, known as Orphism existed already in Greece, but Pythagoras' scientific spirit was not happy with the passive attitude toward life encouraged by Orphism. He created a religious order, which by practical deeds taught the best way of life. The rule that the novices of this order remained in total silence for five years, gives us an indication that Pythagoras had discovered that men were wasting a great deal of energy by speculation and discussion.

In fact, mental activity consumes much energy, leaving less for physical and practical needs. It has been proved that a man of the same age, weight, and height as a woman consumes for the same amount of work more calories per hour than the woman. In my view, this is because of the extra energy consumed by man's active mind while working. Children, whose minds are undeveloped, have far more energy, than adults. We find many periods in history where, with the increased mental activity of a people, there is a decrease in their collective productivity. The collapse of great empires is always preceded by an increased restlessness of mind among the people who built that empire.

Man's energy, in contrast to that of other animals and that of the human female, does not follow a pattern of innate preferences or priorities, because man has neither an innate pattern of behavior nor an innate scale of priorities. Sublimation, the pillar of psychoanalysis which should be an "unconscious process by which a sexual impulse, or its energy, is deflected, to express itself in some non-sexual, and socially acceptable, activity," as we read in A Dictionary of Psychology by J. Drever, is a fallacy. Man's energy is free energy, which is spent pursuing his own personal wishes of the moment, dictated by his mind. Any time the mind decides to concentrate on itself, it consumes so much energy that it leaves very little for other activities. In extreme cases of exaggerated mental activity, as happens with schizophrenics or philosophers, there is no energy left for the elementary needs of the body, or for the social and economic life. When drugs or electric shocks reduce the mental activity of people, thereby reducing the consumption of their energy, they put on weight.

One of the first rational and practical men in history, Confucius, considered it superfluous and derogatory to deal with transcendentality. In fact, his "ideal of normality" transformed the Chinese into the most practical and efficient people in the world.

With its achievements in art, literature, politics, and philosophy, the fifth century B.C. in Greece is considered one of the greatest centuries in the history of mankind.

Ancient Greece, and particularly its fifth century B.C., like childhood for Freudians, resembles a public library where all select what they want to read. From fanatics of democracy to fanatics of fascism, from admirers of art to worshipers of money, from runners in the Olympic Games to runners-away from battlefields, from lovers of competition to partisans of the physical elimination of political opponents, and from hypocrites to homosexuals, they all find facts to suit or justify their preconceived ideas, their pre-assumed attitudes or their actual deeds.

Why was ancient Greece, and particularly its fifth century so glorified and is this glorification justified?

The poetic view of ancient Greece is due to the fact that she was discovered for the first time by the Renaissance and glorified for political reasons, and for the second time by the British and French romantics and the German idealists of the nineteenth century.

In my view, the Golden Century was in fact, one of the most tragic periods of Greek history, which has left damaging legacies to the world. In this period, the human mind entertained not only dangerous absurdities but also the conceit of being proud of them.

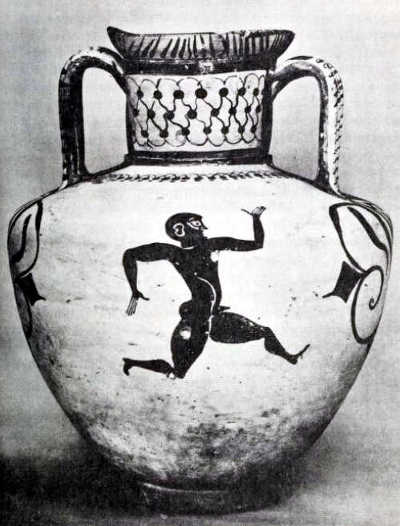

Never in the history of mankind has man reached such extremes of adolescence' and freedom of mind as in the fifth century B.C. in Greece. The mind became so infatuated with itself that every Greek considered himself the center of the universe, each man having his own personal cult or belief in which he felt the greatest. All kinds of competition, from drama to athletics, from riding to riddle guessing, were invented, the aim being that everyone excelled in something. Each man created a new game to suit his own personal abilities. In my view, it was not the Greek sporting spirit which inspired these games, but the desire to excel. Games were not a sport in Greece, they were a means to an end. Competition was agon, antagonism-agony. The competitor was an adversary, a dangerous opponent to be either humiliated or eliminated, by any means. Adolescence is a belligerent stage.

The Greek male found that his mind was omnipotent. Oratory became the means of convincing itself of its own omnipotence. Out of this game came Sophism.

Sophism became so popular that leaders had to open schools all over Greece to teach this new philosophy of life to the self-infatuated Greeks.

What was Sophism, this Greek legacy to mankind?

Protagoras, the leader of Sophism, established the principle of his philosophy by stressing that "man is the measure of everything." This suited the Greek male. Everything became a matter of expediency.

Plato described a Sophist as "the practicer of an art of deception who, without real knowledge of what is good, can give himself the appearance of the knowledge."

To Aristotle, a Sophist was "an impostor who pretends to knowledge employing what he knows to be false for the purpose of deceit and monetary gain. . . ." Aristotle should have added political power. It was, in fact, in the political field that Sophism became so destructive in Greece and subsequently damaging to the world. Sophist demagogy, with its hypocrisy and corruption, produced democracy. This was the discovery of the human mind in the fifth century B.C. in Greece and was another Greek legacy to the world.

Greek society, where wealth and money were signs of superiority soon transformed the fit and unfit into the rich and the poor, the oligarchs and the demos. This produced two contrasting ideas, and divided the Greek world into two opposing sides. One side was obsessed with the production of wealth, the other with social justice and the distribution of wealth, both sides accusing each other of inhumanity and exploitation. The oligarchs claimed that the demos wanted to build a political and economical system, in which the unfit would survive at the expense of the fit, a system which would be "calculated to give an undeserved ascendancy to the poor and the bad over the rich and the good," as one reads in a political leaflet of the fifth century B.C. The demos accused the oligarchs of using their economic power and their political institutions to exploit the poor.

"Betrayal and treason were national pastimes for the Greeks" writes R. Littman in his The Greek Experiment. "The Peloponnesian war began with a betrayal," he explains. "During the course of the war there were at least twenty-seven betrayals or attempted betrayals of the cities."

The corruption, dishonesty, and betrayal embraced by the Greek mind in this period remained a part of Greece for a long time. Polybius, some two and a half centuries later, wrote: "Those who handle public funds among the Greeks, even though the sum may be merely a talent, take ten account-checkers, and ten seals and twice as many witnesses, yet they cannot be faithful to their trust. . . ." "Graeculus" (an expression of contempt that the Romans used for the Greeks) was feared by the Romans - judging by Virgil's sentence "Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes" - even when bringing gifts.

Demagogy, hypocrisy, and democracy are best illustrated through the attitude and deeds of Pericles, who dominated a third of the fifth century B.C. in Greece.

Here I quote his famous speech delivered in memory of the fallen fighter in the battle of 431 B.C. This speech, recorded by Thucydides became a bible for the Democrats, the leaders of the masses, the leaders of the "popular" parties.

Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. We do not copy our neighbours, but are an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while the law secures equal justice to all alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognised; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit, neither is poverty a bar, but a man may benefit his country whatever be the obscurity of his condition. There is no exclusiveness in our public life. . . . While we are unconstrained in our private intercourse, a spirit of reverence pervades our public acts; we are prevented from doing wrong by respect for authority and for the laws, having an especial regard for those which are ordained for the protection of the injured, as well as those unwritten laws which bring upon the transgressor of them the reprobation of the general sentiment. . . . We are lovers of the beautiful, yet simple in our tastes and we cultivate the mind without loss of manliness. Wealth we employ, not for talk and ostentation, but when there is a real use for it. To avow poverty with us is no disgrace; the true disgrace is in doing nothing to avoid it. An Athenian citizen does not neglect the state because he takes care of his own household; and even those of us who are engaged in business have a very fair idea of politics. We alone regard a man who takes no interest in public affairs, not as a harmless, but as a useless character; and if few of us are originators, we are all sound judges of policy. The great impediment to action is, not discussion, but the want of that knowledge which is gained by discussion preparatory to action. For we have a peculiar power of thinking before we act, and of acting too, whereas other men are courageous from ignorance but hesitate upon reflection. . . . To sum up, I say that Athens is the school of Hellas, and that the individual Athenian in his own person seems to have the power of adapting himself to the most varied forms of action with the utmost versatility and grace. This is no passing and idle word but truth and fact; and the assertion is verified by the position to which these qualities have raised the state. . . . For we have compelled every land and every sea to open a path for our valour, and have everywhere planted eternal memorials of our friendship and of our enmity. Such is the city for which these men nobly fought and died; they could not bear the thought that she might be taken from them; and everyone of us who survives should gladly toil on her behalf.

Now I will analyze the objective reality which existed in Athens and which was known to Pericles when he uttered this famous sample of demagogy.

When Pericles glorified democracy he knew that he was the absolute ruler of Athens, who had obtained power by bribing the demos, the masses, and who had expelled all political opponents from Athens. Pericles knew, too, that he was the main architect of the most atrocious war of the ancient world, a war which lasted for twenty-seven years. He depended upon the support of the demos, and he purposely kept the war going to distract attention from their miserable conditions. In the Athens of Pericles, the cradle of so-called democracy, equality, and freedom, out of the 350,000 inhabitants there were only 35,000 rightful citizens. Women, slaves, and foreigners were the object but not the subject of the law. In 451 B.C., Pericles restricted the right of the citizenship of Athens even further.

Under Pericles, woman's position sank to its lowest depths. Even in Sparta, so badly depicted by worshipers of Greek democracy, the judicial, social, and economic position of woman was higher. "The greatest glory of woman," explained Pericles, "is that her name whether for good or ill, should be as little as possible on the lips of man." This was the moral teaching of a man who left his family and lived publicly with Aspasia, a hetaira (*). This contempt for women was yet another legacy of the Periclean age, to the Greeks and to the world. Demosthenes, another great Athenian democrat and demagogue, said: "We have wives for child-bearing, hetairae (*) for companionship, and slaves for lust."

[(*) Ed. Note: For an introductory description of hetaira / hetairae click here.]

Aristotle considered woman even more inferior than did Plato, mainly because of her poor abilities for abstract thinking. Given this low opinion of woman, her conquest was not considered an achievement. The conquest of a male, however, particularly a young boy, was considered a success. Adultery in Greece was not a sentimental or moral offense, but a property offense.

In Pericles' Athens, foreigners were the barbarians, only tolerated if they were useful to the Greeks. Previously "barbarians" referred to those who spoke a foreign tongue. Aristotle repeated the view of Euripides on the inferiority of foreigners when he said: "It is right and reasonable that Greeks should rule over barbarians, for the latter are slaves by nature and the former are free men."

Slaves were treated abominably, most of them working in appalling conditions in the state-owned mines of Laurion and Maroneia. In Aeschylus' Prometheus we read the following advice: "Slave, obey your masters in matters just and unjust."

An example of how the Athenians obtained their slaves is shown when they crushed the rebellious Scione, killed all the male population, and enslaved the women and children.

Justice in the Athens of Pericles, so glorified by many writers, was often nothing but an entertainment for the demos. The law courts were in public places, and the jury, selected from loafers or those wandering around the marketplace waiting to be paid or bribed, was composed of at least 500 members. (The jury which condemned Socrates consisted of 501 members, of which 281 found him guilty, therefore to die, and 220 not guilty.)

It was not democratic justice, it was a demos' justice. No woman, slave, or foreigner stood a chance against this kind of jury. A learned or rich man lost his case if he addressed the jury in his own language and in his own cloth. (Any Mediterranean group of poor people or loafers, even today, take pleasure in deriding those who differ in some way from themselves.)

From Lysias' twenty-fifth speech, we see what pleased the jurors, when reading the plea of a defendant: "I made many contributions of money to public finances; and I performed the other 'liturgies' in a manner not inferior to any other citizen. And I spent more money on these than I was required to do by the city so that I might be thought more agathos by you, and if some misfortune should come upon me, I might be judged with more sympathy by the court." In Lysias' third speech we read the address of another defendant to the Athens jury: ". . . and do not overlook the fact that I am being unjustly expelled from my country, for which I have endured many dangers and performed many liturgies and have never caused it any harm, neither I nor any of my relatives, but rather many good deeds." From these speeches we see that spending money on liturgies, enabling the lazy and poor of the city to enjoy life or find something to do, was an important, sometimes even decisive, circumstance on which the verdict of the jury was based.

Athenian international inter-cities justice was pure expediency. This expediency is evident in Thucydides' description of an Athenian representative addressing the following words to the representatives of the small city-states of Melos, defeated by the Athenians: "You know as well as we do that right, as the word goes, is only a question between equals in power, whereas the stronger do whatever they must." The same writer describes Cleon's advice to the Athenians on how to deal with the rebellious Mytilenians in the following lines: "You will do what is just towards the Mytilenians and at the same time what is expedient. . . . For if they were right in rebelling, then you must be wrong in ruling. . . ." Whether the Mytilenians were right or wrong, Cleon concludes his speech with the words "You must punish the Mytilenians as your interest requires."

In The Republic, Thrasymachus expressed the general opinion on justice and international justice when he said: "I proclaim that justice is nothing but the interest of the strong. . . ."

Another of Pericles' legacies to the world was ostracism. Ostracism was the banishment of political opponents from the country.

In The Greeks and the Irrational, E. R. Dodds explains this: "But the evidence we have is more than enough to prove that the Great Age of Greek Enlightenment was also, like our own time, an Age of Persecution - banishment of scholars, blinkering of thought, and even (if we can believe the tradition about Protagoras) burning of books." In fact, Plato wanted to burn the works of Democritus. This wish, like many of Plato's wishes, was fulfilled in the end by Christianity.

What was the reason for the persecution of political opponents?

Political and religious persecutions were and still are carried out by demagogues playing with the ignorant masses. Demagogues only succeed during an era of corruption and bad faith. They succeed by accusing their opponents of corruption or impiety. This arouses the false indignation of the masses. Nothing is more aggressive than the false indignation of the masses. With false indignation the masses try to cover up their own corruption and bad faith. They feel safer accusing others.

Another catastrophic legacy left to humanity by the Athens of Pericles was civil war. The Greek adolescent mind, in its inability to solve the problem of a pattern of life, produced a general fratricide, all Greeks killing each other in the name of abstract beliefs, nurtured by the demagogues. It was even considered heroic to kill one's friends and relations, and above all one's own progeny. Thucydides' description of the Greek Civil War illustrates this Greek legacy. "The ties of the party were stronger than the ties of blood: revenge was dearer than safety: the seal of good faith was not a moral law, but fellowship in transgressing it. Treacherous antagonism everywhere prevailed: for there was no word binding enough, no oath terrible enough to reconcile enemies. The leaders of either party used specious names, but all they wanted was power. They were carried away by senseless rage into the extremes of merciless cruelty and committed the most frightful crimes. Neither justice nor the public interest could set any limit to their revenges. The father slew the son, and the supplicants were dragged from the temples and slain."

In my view the Greek Civil War, as any civil war, was caused by adolescent fury at being unable to find a solution to the problem of organizing life on the level of self-infatuation. My view is strengthened by the following lines from Thucydides: "Reckless audacity is considered the courage of a loyal ally; prudent hesitation, specious cowardice, moderation, to be a cloak for unmanliness; the ability to see all sides of a question, a sign of incapacity to act on any. Frantic violence became the attribute of manliness. . . ." "The oath of reconciliation" was nothing but an expedient, "good as long as no other weapon was at hand; but, when opportunity offered, he who first ventured to seize it and to take his enemy off his guard, thought this perfidious revenge sweeter than an open one since, consideration of safety apart, success by treachery won him the palm of superior intelligence. Indeed it is generally the case that honest men are readier to call rogues clever than simpletons honest. . ."

What was "the cause of all these evils"?

"The lust for rule arising from greed and ambition," explained Thucydides.

Admirers of the Athens of Pericles will by now be shocked, ready to argue, "What about the Parthenon and the great Phidias?"

Pericles' policy ruined the agriculture industry, and Athens became a refuge for thousands of former landowners. These masses could not be kept merely by being paid or bribed as jurors, or with "liturgies" and festivals, although there were seventy various ceremonies a year in which the poor were fed free. In order to keep these masses calm and occupied, Pericles started public works with public money, and money from his allies. The monuments erected in this era were not inspired by Pericles' aesthetic sense, they were the needs of a demagogue. The Parthenon, and other Periclean monuments, although beautiful for some, are merely public works. To judge Pericles by the Parthenon is like judging Mussolini and Hitler by their auto routes.

In the end Pericles was brought before the court for the embezzlement of public funds. Phidias, Pericles' ally in public work, died in prison accused of stealing material and money given to him for statues.

Besides, one cannot judge a political system by artists of its period. Can the outrageous policies of the Borgias and Pope Julius II be judged by the works of Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Sansovino? Can the adventurous policy of Ludovico il Moro be judged by the works of his protege, Leonardo da Vinci?

Most Greek tragedies can be attributed to the Greek polis, which a chain of political writers throughout history have glorified as the ideal form of state. The polis, however, was a necessity for the Greek adolescent male. He felt secure in a small, protected polis, secure in his self-infatuation.

Studying Greek history we gain the impression that civil wars and massive mutual killings were performed to save the polis from overpopulation, the polis only being able to exist with a limited number of citizens. Every Greek felt important in his small polis. In order to give every citizen a chance to become a member of the Council of the City State, there being a limited number of posts, no one was a councilor more than once and for more than a year. The polis was in character with the Greek adolescent.

In a small city-state everyone knew each other, everyone was a neighbor of the rest of the community. This was the price that the Greeks had to pay for their illusions of importance. Knowing each other so well nourished envy, jealousy, and antagonism. The vindictiveness of neighbors was the cause of strife and civil wars between the oligarchs and the democrats. There was little difference between the two parties, in any field of administration. There was no such difference, however, to justify either of the parties in joining the enemy of their polis in order to fight against its own city-state. It was in the nature of the polis, as it is in the nature today of any small community, to have two gangs fighting each other to kill. That the difference between the oligarchs and democrats was only an excuse for the extermination of local enemies can be deduced by the fact that often alliances of one group of a polis were made with their national or ideological enemies. The depth of hatred between the two gangs can be detected in the following description by Isocrates: "The owners of goods would prefer to throw them into the sea than to alleviate the misery of the poor, and the poor would be happy not so much as to take goods from the rich but to deprive the rich of these."

This Greek legacy to the world was particularly welcomed in Germany during their Thirty Years' War, where the Protestant states begged help from Catholic France in their fight against the Catholics who in turn were asking Protestant Sweden to help them.

In a society where women were treated so badly, it follows that work would be despised. Contempt for work was, in fact, another Greek legacy to mankind. "Work degrades men and makes them equal to animals," is a popular Neapolitan saying even today.

In Sparta, any manual work was considered degrading, but idleness and leisure meant dignity and freedom. In Plutarch we read: . . . "this shows how much the Spartans considered any trade and handicraft base and servile." There was a law in Sparta forbidding citizens to work in any wage-earning trade.

In Plato's Republic we read: "It is fitting for a man to despise work." Plato's philosophy was that there should be an elite, an elite living in leisure. This was the only way to achieve wisdom.

To Aristotle "all manual works are without nobility; it is impossible to cultivate virtue and to live as a wage earner." In his Politics we read: "Wage earnings do not leave the mind either freedom or a chance of elevation." In Aristotle's view, leisure was necessary to "cultivate a virtuous soul, and to fulfil civic duties." He found nature generous because "it has produced a species of beings, slaves, who used their bodies to replace our fatigue."

According to Xenophon, Socrates said, "The workers and their handicraft are discredited and despised in the cities." . . . "With a weakened body, the mind weakens too. . . ."

In the third century B.C. we have evidence that even highly skilled work was considered undignified for a superman. Plutarch explained that Archimedes considered his engines and his technical inventions as merely "play for his geometry. . ." "He considered mechanics, and in general all artifacts, which are born out of need, as ignoble and base. . . ." Archimedes loved science, Plutarch explains, because "its beauty and its excellence have nothing to do with necessity."

At the beginning of the fourth century B.C., after the adolescent Greek mind had reduced the whole of Greece to economic ruin and moral chaos, a unique phenomenon occurred which became another Greek legacy: the glorification of madness, the same madness which had brought the ruin and chaos. In Plato's Phaedrus Socrates says: "Our greatest blessings come to us by way of madness. . . ." "Provided the madness is given by divine gift." With confusion of the mind, any madness becomes a "divine gift," "divine madness" or "sacred disease." The Greeks interpreted any irrationality even mental illness and abnormality, including epilepsy, as caused by the possession of some god, and therefore capable of inspiring luck - good or bad. Madness and abnormality began influencing human behavior. Through the practice of defixiones, even the dead were used to help the life of these Greeks unable to find a stable pattern of life.

The beginning of the fourth century B.C. in Greece was the perfect atmosphere for Philosophism, to use this expression invented by the French Encyclopedists. It was an atmosphere in which each individual mind was searching for an abstract or supernatural guideline for earthly life. Plato could only have been born into this atmosphere of Philosophism.

Plato invented a paradox of the human mind, a paradox which will be permanently repeated throughout history. (The word "paradox" is of Greek origin.) He started curing the confusion of the mind with the same mind which created the confusion. He wanted to solve the problem created by speculation, by increasing the speculation. This meant that to cure a physical illness, one had to make it worse. Plato thought that the only way to organize earthly life was to climb higher into transcendality.

In fact, through higher speculation in The Republic, Plato created an ideal state, a state suspended in the clouds of his imagination. This ideal state, however, could not solve the earthly pattern of life. It was too far removed from reality.

The ideal state created by the mind is known today, following the Thomas More term, as Utopia, meaning "nowhere." An even more appropriate name can be found in Aristophanes' satire The Birds. In this satire the birds are asked by two deluded citizens of Athens to build an ideal state, a polis in the air. All Utopias should be called "states in the air" or "cloud-states."

Plato only knew two kinds of standard men: one evil, the product of tyrannies, and one mediocre, the product of democracies. His ideal was a good standard man.

How did Plato's ideal state intend to produce a good standard man?

Platonically! After two years of military service, every single young citizen had to spend the next five years studying philosophy. The ruling class of Plato's ideal state was chosen from among the best philosophers, from those who had achieved clear ideas about the ideal entities: justice and goodness. This ruling class had to be above standard men. It had to consist of supermen. In Plato's view, this elite could only attain ideal entities through leisure and idleness, therefore living apart from economic and social reality. "Until philosophers are kings and kings philosophers there will be no salvation for states or the souls of men," he wrote.

With Plato's ideal state, an eternal question started: Who was to educate the educators of the ideal state? Modern Utopias answer this question by showing that the educators, in order to educate, do not have to be educated, just indoctrinated.

Plato claimed that all human behavior should be inspired by supreme good. What was this supreme entity that was supposed to direct human lives?

In the following letter, he admits that he has no idea: "There is no writing of mine on this subject, nor ever shall be. It is not capable of expression like other branches of study; but, as the result of long intercourse and a long time spent upon the thing, a light is suddenly kindled as from a leaping spark, and when it has reached the soul, it thenceforwards finds nutriment for itself." This supreme entity, of Plato "was hard to find and impossible to describe to the masses," said Timaeus, a biographer of Plato.

Cynical contempt of humanity, the common man in particular, is the main characteristic of all Utopians. At the entrance to his academy Plato wrote: "Let no one who is not a geometrician enter here."

That Utopians despise human beings can be deduced from the way humans are treated in Utopia: as inferior beings. The result of this is that all Utopias are despot governments or tyrannies. Plato's view was that man, being a "puppet," could easily adjust to the abstract idea of the ideal man, the man created in the mind of philosophers.

How was Plato's ideal state organized?

It was a church-state in which civil life was conducted as a religious performance. In this church-state, general abstract beliefs were fixed as laws of state, and imposed on the collectivity. Breakers of the law were punished. For minor offenses against the official state religion, the punishment was five years in a reformatory. Punishment for major offenses was banishment, solitary confinement for life in a particularly unhealthy or dangerous place, and death.

Intolerance toward ideas in contrast with official church-state doctrines, and its corollary, the persecution of heretics or "ideological enemies," was another of Plato's legacies to humanity. He was the first to discover ideological intolerance, the first to realize that the value of a belief was directly in proportion to its power to eliminate other beliefs with its monopoly, a word invented by the Greeks.

Plato's academy survived until the sixth century A.D., when, in the name of his own idea of persecution, it was closed down by Justinian, to make room for a new official belief, Christianity, mainly inspired by Plato, through Neo-Platonism.

All Utopians, from Plato on, have had no sense of humor, therefore no sense of the ridiculous. They are prototypes of adolescents, always floating on a cloud of gloom. If Plato had had a sense of humor, he would have laughed at Aristophanes' satire The Birds, in which the humorous and ridiculous side of Utopias is shown.

The tragedy is that Plato has been used as a model by all other abstract speculators throughout history, speculators in search of an imaginary ideal state and an abstract pattern of life for male dominated humanity. Only recently, after centuries of tragic and disastrous ventures by the human mind, are there signs of doubt that the mind can give or indicate a solution to the problem of finding a pattern of life. "with me the horrid doubt always arises as to whether the convictions of man's mind, which has been developed from the lower animal are of any value, or are at all trustworthy," wrote Darwin (from Darwin's Life and Letters, by Francis Darwin). H. G. Wells gives us a pathetic confession when, at the end of his life, he wrote Mind at the End of Its Tether, a book of great wisdom crammed into just thirty-two pages. We quote the following passages from it, hoping to put doubt into the minds of people who have faith in their mind:

. . . "That sceptical mind may have overrated the thoroughness of its scepticism. As we are now discovering, there was still scope for doubting. The severer our thinking, the plainer it is that the dust-carts of Time trundle that dust off to the incinerator and there make an end to it. . . ." "Our world of self-delusion will admit none of that. It will perish amidst its evasions and fatuities." "Mind near exhaustion still makes its final futile movement towards that 'way out or round or through the impasse.' That is the utmost now that mind can do. And this, its last expiring thrust, is to demonstrate that the door closes upon us for evermore. There is no way out or round or through. . . ."

In 1932, Henri Bergson, in his Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion, claimed that Plato "in spite of 2,000 years of meditation about his ideas" did not advance our knowledge of ourselves one step. Bergson was right, not only as far as Plato was concerned, but as far as all philosophers are concerned, or anyone for that matter who pretends to solve the problem of earthly life by philosophizing about it. It is interesting to note that the philosophers hate each other, a clear evidence of the fragility of their worlds. For Schopenhauer, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel were nothing but "the three sophists." "If I had my way," wrote Roger Bacon, "I would burn all the books of Aristotle, for the study of them can only lead to a loss of time, produce error, and increase ignorance."

For centuries men have considered women inferior beings, as they are incapable of being philosophers, or abstract thinkers. In fact, women find all philosophies laughable. Men's attitude is that of drug addicts. They consider those who do not take drugs as inferior.

With all the negative legacies that ancient Greece left humanity, she also left a positive one. The Greeks discovered the only solution for a mind at the end of its tether. When completely lost in his abstract thinking, the Greek male would go to Pythia in Delphi for advice, common sense and a touch of realism and reality.

Pythia of Delphi was well known, but each polis had its own Pythia, and sooner or later every Greek man ended up with his own personal Pythia in search of common sense.

With the Delphic Pythia, man's mind encountered the following irony. In order to enable men to accept her common sense, Pythia had to play their game, and pretend that her natural logic was inspired by a supernatural power; she had to pretend to be in a trance; she had to give the impression of being possessed by a deity, when giving advice. Man can never accept common sense in a simple way; he has to believe in it. To be accepted by man, common sense must be "inspired prophecy," given in an "ecstatic state."

Men believed in Pythia because they thought that she was possessed by a wise deity. At the same time they were aware that there was no wise deity in the Greek Pantheon, as Metis, the goddess of Wisdom, was swallowed by Zeus when she was pregnant.

Many writers consider that Pythia's wisdom was inspired by Apollo, Apollo being the protector of Delphic oracles. But was Apollo really such a wise god? He committed one of the most unwise of deeds when he placed himself on the losing side on the Trojan War.

The divine madness of the fifth and the beginning of the fourth centuries B.C. produced economic misery. This misery can be seen in several plays of the period, and particularly in Aristophanes' Plutus.

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com