Index

| Parent Index

| Build Freedom:

Archive

PART 3

The Mind in Search of a Pattern

STOICISM

"Any mature woman is a Stoic by nature."

"We know that consensus . . . could only have been accepted as a source of laws in a culture influenced by woman."

"The other important Roman virtues were pietas, gravitas, and sublimitas."

"The cult of work. . ."

The via Flaminia, part of "this network of roads."

"The cult of cleanliness. . ."

The conceited Greek mind and its great achievement, demagogy, along with its champion, Demosthenes, the Athenian democratic leader, suffered a major defeat. In 338 B.C. at Chaeronea, Philip of Macedonia quelled the last Greek resistance and united Greece for the first time in her history.

The Greeks should consider their defeat at Chaeronea as beneficial to themselves and to mankind. It marked the end of an era. It was the destruction of the cradle of the Greek mind's self infatuation, of the polis.

Philip of Macedonia and Alexander the Great put an end to city-states, in which every citizen was a king in his imagination. When the polis walls crumbled, the fresh air from the outside world cleansed the marketplace of its prejudices. With the empire of Alexander the Great, the Greek found himself part of the universe, instead of being the center of it. The Greeks found themselves lost in the wilderness of a new savannah.

Faced with the universe created by Alexander the Great, Greek men started to doubt the power of their mind, started retreating from their adolescent self-infatuation. The Greek male discovered woman. The cult of Cybele, the Great Mother of Asia Minor, and the cult of the Egyptian Isis, became popular.

Instead of the tragedies typical of the fifth and first half of the fourth centuries B.C., we have, with Philemon and Menander, the New Comedy era. In the New Comedy era, the Greek ceased to be static and egocentric. He moved, traveled and noticed others. Ordinary people with their everyday life were the themes of the comedies of the time.

With the new era, culture and science flourished. With culture, the Greeks discovered logos; through science they discovered the cosmos. Two schools expressed the new atmosphere: Epicureanism, and Stoicism. We will concentrate our attention mainly on Stoicism because of its important contribution to the grandeur of Rome, and particularly to the grandeur in the second century A.D. when Stoicism, the Roman Empire, and human civilization reached their peaks.

Human behavior should never be imposed by the mind, but by logos, by universal reason, the Stoics explained. Their attitude was "The sage lives in accordance with reason." "Quid est ergo ratio? [What is reason? ]," Seneca asked himself. "Naturae imitatio [the imitation of nature]," he answered.

How can man embrace this attitude? By imitating woman's attitude to life. Any mature woman is a Stoic by nature. Stoic logic, a natural logic, is in its essence woman's logic; its precision and simplicitas is in contrast to man's logic, the logic of easy generalizations, approximations, assimilations, analogies, or hypotheses.

When the Greeks started preaching Stoicism, the Romans were already living as Stoics. This can be deduced by Lex Hortensia. This famous law of 287 B.C. emerged as a new way of creating laws: by consensus bonorium, through plebiscitum. We know that consensus is in woman's nature, and could only have been accepted as the source of laws in a culture influenced by woman. In man-dominated societies laws are imposed.

The Romans emphasized positive and active virtues such as magnanimity, benevolence, liberty and, above all, humanitas. Hadrian used humanitas with felicitas and libertas as the motto of the Empire. He illustrated the Roman meaning of humanitas on his coins. He was depicted raising a weeping woman to her feet.

The Roman's positive meaning of humanitas can be read in the following words repeated by Cicero and Terence: "Homo sum, et nihil humani a me alienum puto," meaning, "I am a man therefore humanity is part of me." This is a feminine attitude. Woman's humanity is part of her nature, her instinct for the preservation of the species. Man, in his nature, is not humane; he can only either imitate woman's humanity or be guided by an abstract idea of it, which precludes from humanitas the opponents of his idea of it.

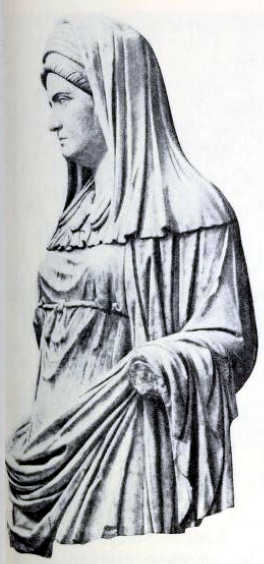

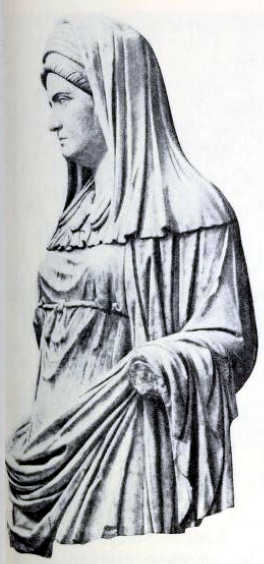

The other important Roman virtues were pietas, gravitas, and sublimitas. These are attributes of the female nature.

What is the difference between a good deed inspired by the mind, and a good deed inspired by pietas and humanitas? In other words what is the difference between the good deed of a man and the good deed of a woman?

A man's good deed is the materialization of an abstract or religious idea of good. Man's good deed is a believer's good deed. The believer's good deed is never inspired by real need for good, but by his mind's need to do good.

Good deeds inspired by humanitas and pietas, woman's good deeds, are different. They start from outside, from the real need. The purpose of this good is to help the needy to their self-sufficiency, their dignity.

The following two sentences of Ovid explain the Roman meaning of virtue, an excellence in behavior dictated by intelligence, understanding, intuition, or common sense. In medio stat virtus and Medio tutissimus ibis. Virtue, for the Romans, was therefore in the middle, in between extremes. Exaggerated deeds, even if they were good deeds, produced negative effects in the eyes of the Romans. According to Tacitus they produced hatred and ingratitude.

Roman virtus was feminine in character. This is understandable if we take into consideration the following facts. Virtus comes from vir which means "man." Virtue, therefore, meant the behavior or attitude of a serious man. Who then defined the meaning of the word virtue? In a culture dominated by women, it will be the women who dictate what is virtuous, what the correct behavior is for the men.

There is some difficulty in understanding the Roman's real meaning of virtue, because the period of beliefs, which came after Rome collapsed, created believers' virtues or ideological virtues, which are a contradiction in terms. In belief, virtue means excess, simply because in beliefs, virtues are servile instruments of the beliefs.

Roman Justice

Stoicism helped the Romans to create their Jurisprudentia, a unique phenomenon in the history of mankind. It was a legal system based, "not on a theory but which came out of frequent conflicts and practical crises," as the historian Polybius explained.

Jus naturale, or jus naturae was based on the Stoic view of the open universe, of universally valid natural laws.

Jus gentium could have only been inspired by Stoic cosmopolitanism.

The famous Lex Aebutia of 150 B.C., which authorized Roman judges to overlook positive laws whenever equitas, reason or common sense required it, could only have been inspired by the Stoic cult of wisdom, by natural or universal reason.

Rome invented equitas and based her legal system on it. What was the real meaning of equitas?

It is difficult today to describe the real meaning of equitas, because it died with Rome, and because since the fall of Rome humanity has only known man-made justice. Man's justice is a rigorous and codified justice. Its rigidity is justified by the consolation that it is equal for all. Man's justice is inspired by prejudices, abstract ideas, doctrines, beliefs, or infatuations. Equitas was justice without prejudices, justice without laws, and often it was justice against laws. In fact, this was the meaning of Lex Aebutia.

The following two sentences were the guidelines of the Roman judges: Aequitas praefertur rigori, meaning that equitas is preferable to rigorous laws, and Aequitas de iure multum remittit meaning that equitas softens laws.

Equitas is a Stoic virtue, and justice based on equitas was a supreme virtue. "Iustitia omnium est domina et regina virtutum," stressed Cicero in De officiis, calling justice the queen of virtues. Only by considering justice as the supreme virtue, can one understand the principle of Roman justice, of Summum ius summa iniuria, meaning that excessive rigor in justice creates injustice.

Work in Rome

Given the respect for woman in Rome, we may assume there was respect for work. In fact, Rome's greatness was built on respect for woman and the appreciation of work.

Around 700 B.C., during the reign of King Numa Pompilius, according to Plutarch, there were already collegia, professional corporations.

King Numa Pompilius gave land to all wishing to farm it, "even to the poorest of citizens," wrote Plutarch, "hoping that by bringing them out of their misery, to free them from their unfortunate necessity to commit evil deeds, and hoping that by leading a peaceful and healthy country life, these poor citizens would become more gentle, and hoping that in cultivating the land, they may cultivate themselves." King Numa Pompilius traveled around "to judge people by their work," Plutarch said. This wisdom, at the dawn of Rome's existence, is what made Rome's civilization the greatest ever known.

What kind of worker was the Roman?

He was conscientious and productive. This is shown in the following two sentences characteristic of Ancient Rome. "Age quod agis," Plautus suggests in his Persa; meaning, whatever you do, do it well. "Aut non tentaris, aut perfice," Ovid advises in his Ars Amatoria, meaning: Think before starting something, and if you start it, finish it. In work, more than in any other field, Roman gravitas was felt.

The cult of work can be deduced by the following line of Seneca in his Epistulae Morales: "Nibil est quod non expugnet pertinax opera, et intenta ac diligens cure," meaning that there is nothing that cannot be won with persistent work, and attentive and diligent care.

Work to Virgil was an instrument for the betterment of humanity. This great poet of nature expressed his optimism and confidence in his Georgics with the following words: "Labor omnia vincit improbus," meaning that hard work beats everything.

To Marcus Aurelius, work was the reason for one's existence.

The popular Roman proverb Frater qui adiuvatur a fratre quasi civitas firma, meaning that a strong city can be built with brother helping brother, shows us that the Romans were cooperative rather than competitive, which is, after all, in character with any society influenced by woman and her sense of organization. The co-operation went from the level of the familia to the level of the empire. The symbol of the empire was a bundle of rods tied together.

This co-operative division of labor produced specialized productions. Padua specialized in the production of linen, Rome in embroidery, Taranto, Potuoli, and Ancona in purple, Syracuse and Cunae in woolen goods. Judging by Pliny the Elder there were some candelabra of which the upper parts were made in the island of Aegina, and the lower in Taranto.

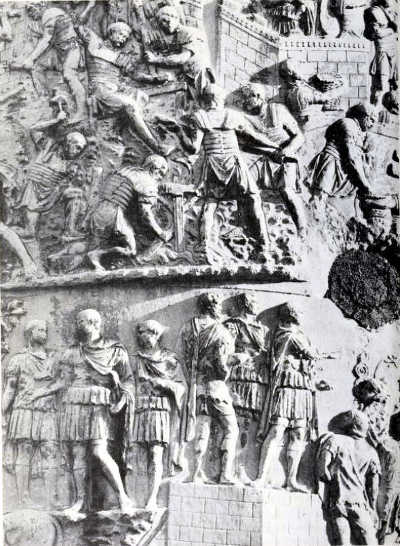

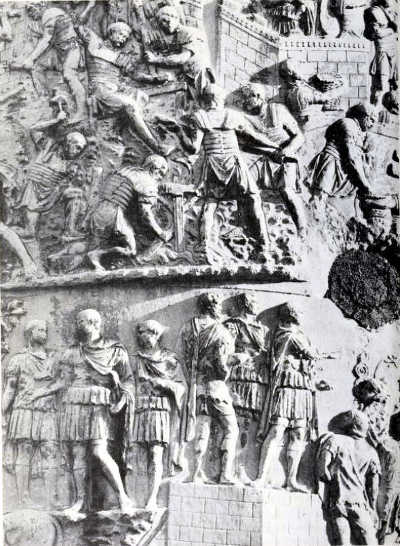

The transport of the goods by the negociatores, or tradesmen, from the production areas to the markets of the empire were facilitated by the great Roman roads. This network of roads is yet another proof that the economy leaned on co-operation. Greek

antagonism and competition, in economics, games and in life, never caught on in Rome, before the third century A.D.

But how, in practical terms, did this co-operation in Rome work? What was the power behind it?

The answer is senioritas. Based on age, the rule of seniority operated Roman co-operation, from Senate and magistracy to agriculture and trade. Apex senectutis est auctoritas, and Cicero in De Senectute: Senioritas and auctoritas went together in Rome. They inspired reverentia which was the incentive which operated in Roman society, based on co-operation. Respect for senioritas is more in the nature of women than in men.

Satires

Rome gave the world a new literary form, and a name to it. It was the satire of satura. In this literary creation we can find the specific characteristic of Roman culture. The Greeks gave us tragedies, tragedies mostly about woman; the Romans gave us saturae, satires mostly about men. These literary works represent two worlds: one dominated by men, the other by women. The Greeks depicted abstract and absurd characters and problems in tragic form; the Romans depicted real characters and problems in a humorous form.

Only a society which knew shame, a society where pudor existed, could have created saturae. Only in a society where man is in pre-adolescence, a stage in which maternal influence is still felt, can satires have a reason for existence, a real meaning.

In essence, the Roman satire was a maternal reaction to extreme attitudes or exaggeration in behavior. Scholars explain that the word satura comes from the Latin word satur, meaning a "medley" a "mixed stuffing," and "miscellany." In my view, the noun satura stems from the verb saturare, meaning that one has had enough, that one has reached saturation point. A satura is the reaction to saturation. It was the natural and spontaneous reaction in a shame culture. "Why do I write satires? Say, rather, how could I help it?" writes Juvenal in the introduction to one of his satires.

There are two main reactions to extreme attitudes and exaggeration in behavior: maternal and paternal. The paternal reaction is the order to stop extreme attitudes and exaggerations, the violent elimination of them and the punishment of those who exaggerated in order to give an example for the future. The paternal reaction is caused by provocation and so becomes a further exaggeration.

To a mother, any extreme behavior is merely a lack of common sense. The aim of her reaction is to awake common sense in the exaggerator, a sense of proportion and harmony. The only way to invoke common sense in someone who has lost it is to let him know that he has exaggerated. Women do it with humor, irony, mockery, jokes, and ridicule. In woman's view, man can stop exaggeration by eliminating it physically or by punishing those who exaggerate, but this does not establish common sense. "Pudor si quim non flectit, non frangit timor," said Publius Siro, the Roman poet of the first century B.C., meaning that fear cannot break what shame cannot bend. That shame was an important break of extremes and exaggerations can be deduced by the following sentence of Seneca: "Quod non vetat lex, hoc vetat fieri pudor," meaning that what is not forbidden by laws is forbidden by shame. Juvenal considered pudor the safest guideline in life when he said: "Summum crede nefas animam praeferre pudori," meaning that big troubles are caused by preferring life to pudor.

That satura was held in high esteem in Rome, can be deduced by the fact that the great satirist Varro (116-27 B.C.) had his statue erected in the public library when he was still alive.

Roman satura was a creation of the Stoics. It was their reaction to the exaggeration of self-infatuation, of abstract speculations and absurd attitudes. The Romans were always suspicious of abstract speculations and Greek philosophizing. Lucian complained that the Romans preferred an "Alexandrian dancing master" to a "Greek philosopher." We can find the mockery of abstract speculations and sophistry in most of satires.

Juvenal criticized Greek philosophers and Jewish "professors of magic and prophecies" who were able to "sell you any dream you wanted for small change." The Greek will even seduce your grandmother, Juvenal claimed, if there was no one else available. "At any time of day or night a Greek is able to take his expression from another face," he wrote.

With the third century A.D., satura vanished from Rome. With the third century the Roman male entered the adolescent phase, the phase in which mockery was purposeless: there is no shame in adolescence. With Christianity, satura and satirists were persecuted.

Hygiene

The first move an animal makes after giving birth is to lick her offspring clean.

The cult of cleanliness is always prevalent in societies influenced by women. A peculiarity of Rome, which illustrates Roman culture, was the thermae, the baths.

The thermae of the Roman Empire were not just reserved for the privileged. Agrippa made the thermae free, and bath oils were gifts from the emperors. At the beginning of Christianity there were about 11 large public baths in Rome, and 856 smaller ones. Some, such as the baths of Caracalla and the baths of Diocletian, had about 5,000 visitors a day, and could hold 1,600 people at the same time.

One of the first things that the Christians destroyed were the thermae, and after a few centuries of Christianity Rome had not one public bath.

The Romans gave more importance to hygiene than any other peoples before or since. The Roman motto Mens sana in corpore sano could only have been maternal advice.

Hygeia, the goddess of cleanliness, was worshiped as much as Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Her name was mentioned with that of Hippocrates in the oath of medical professions. "We can therefore conceive Stoicism as a spiritual hygiene," wrote Schopenhauer in his The World as Will and Idea.

It should be emphasized that the Romans considered the baths natural and kept them for physical necessity, without transforming them into a pleasure. This can be deduced from the following sentence of Seneca in his Epistolae: "Curam nobis nostri natura mandavit; sed huic ubi nimium, indulseris, vitium est," meaning that nature demands care of the body, but that any exaggeration of it is a vice.

Index

| Parent Index

| Build Freedom:

Archive

Disclaimer

- Copyright

- Contact

Online:

buildfreedom.org

| terrorcrat.com

/ terroristbureaucrat.com