Many traditional cheaters use flagrant ploys to deal themselves good hands. As crude as their ploys may be, however, they often work when blended with basic Neocheating maneuvers of blind shuffling and false riffling. For example, some amateurs pretend to count the cards face up to make sure the deck is complete (e.g., "This deck doesn't feel complete", or "Are you sure the cards are all here?" are common signals). During their ploy, they casually cull aces to the top or bottom of the deck and proceed to center cut and crimp. Then a few blind shuffles and a false cut or two make their ploy effective.

Essentially all effective cheaters today mix at least some Neocheating into their techniques. Indeed, the Neocheating portion of their techniques makes them workable. The pure Neocheater, however, uses only the simple and invisible techniques described in this book. Crass ploys such as described in the above paragraph are never used or needed by the pure Neocheater.

Blind shuffling is crucial to the Neocheater. He automatically and constantly blind shuffles -- with deadly effects. Blind shuffling is easy. With about two hours of practice, anyone can appear to thoroughly shuffle a deck of cards while actually leaving the upper half or two thirds of the deck (the stack) undisturbed.

Blind shuffling is a key tool for Neocheaters. Any suspicion aroused by awkward or hesitant movements in the process of stacking is dissipated after a few blind shuffles and a false cut. In fact, in many games, a player could simply spread cards on a poker table and laboriously stack them one by one as other players watch, but as long as he thoroughly blind shuffles the deck afterward, no one will accuse him of cheating.

So effective is the blind shuffle that a person can stack a number of cards, blind shuffle and then convince opponents that their cards are marked by reading the values of the cards prior to turning them over one by one. Or he can convince players that he is a "psychic", able to read the backs of cards with his eyes tightly shut while his fingertips "feel the vibes". He can fool anyone -- not only mystics, but scientists, businessmen, poker professionals -- anyone except another Neocheater or the reader of this book.

Ironically, intelligent men can spend thousands of hours playing cards, but know nothing about manipulating them. And almost all honest cardplayers are ignorant of Neocheating maneuvers. "I can spot a crook anytime," is one indicator of an easy target for the Neocheater. The Neocheater loves to encounter the closed mind. He knows how easy it is to empty the wallet of the man who thinks he knows everything.

Professional cheaters generally disdain tricks such as "proving" cards are marked or "reading" them with their fingertips. Professionals call those tricks cheap flash, but such tricks demonstrate the seemingly miraculous effects of blind shuffling.

Commencing with the blind shuffle:

Step One: Assume that you have stacked the deck using either discard stacking or methods described later. You now need to produce the illusion of thoroughly shuffling the deck before dealing. So begin by preparing for what appears to be a normal overhand shuffle by placing the deck in your left hand as shown in Figure 13. Note the position of the fingers on the deck: Thumb on top, forefinger placed against the front edge, two middle fingers on bottom, and the little finger curled around the rear edge. Hold the deck so it feels comfortable and natural. (Neocheaters generally use those finger positions when shuffling blind or otherwise.) Tilt the upper end slightly downward toward the table to facilitate faster shuffling and to keep the cards from flashing. With your right hand, pull half the deck or less from the bottom using the two right center fingers and right thumb on opposite ends. The right forefinger should rest on top of the deck portion just pulled out by your right hand.

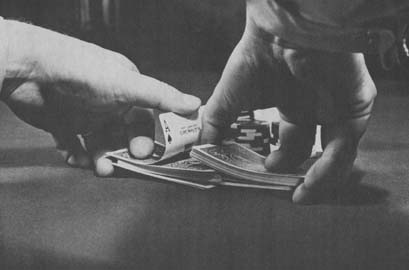

Now, using your left thumb, slide the top card from the deck portion in your right hand onto the deck portion retained in your left hand. But jut this top card toward you about an eighth of an inch (or slightly more) so that it protrudes a little from the rear of the deck in your left hand. Your curled left little finger will rest against this jutting card on top. Now casually overhand shuffle the remaining cards in the right hand, a few at a time, onto the top jutting card in the left hand. The jutting card is now located near the middle of the deck, and your cards should look approximately like those shown in Figure 13. The jutting card, hereafter called the break card, creates a break in the deck not visible to others. The half of the deck beneath the break-card is the stack. That portion of the deck will remain intact.

Step Two: Withdraw the lower part of the deck, the stack, with your right hand, up to but not including the jutting break card, and throw this entire portion on top of the cards in your left hand, briefly squaring the deck with your right fingers. Now the stack sits again undisturbed on the top; yet, the deck appears to be shuffled.

Repeat steps one and two for ten minutes, doing the steps as relaxed and smoothly as you can. Do not worry about speed; simply get the feel of that jutting break-card. Your left little finger should be brushing the break-card, and your right thumb should easily feel the break-card as you pull out the stack. Try for a natural rhythm, a casual pace. After the first ten minutes of practice, you should not have to look at the cards.

The Neocheater does not worry about others being conscious of the jutting break-card; the deck is in constant motion and looks perfectly normal. For anyone to see the break-card, they would have to stand directly behind the dealer. Even then the deck would look normal, for no one shuffles cards with the edges of the deck precisely squared at all times. Ideally, the break-card should protrude no more than an eighth of an inch, although protrusion varies from time to time up to a quarter of an inch.

Now, prepare to repeat the overhand shuffle in Step One by placing the deck in the left hand as shown in Figure 13. The stack is on the top. As before, with your right hand, pull half the deck or less from the bottom using the two right center fingers and right thumb on opposite ends of the deck. Then using your left thumb, slide the top card of the deck portion just pulled out by your right hand onto the deck portion retained in your left hand. Jut this top card toward you about an eighth of an inch, protruding slightly from the rear of the deck. Your curled left little finger will rest against this protruding break-card. Now overhand shuffle the remaining cards in the right hand on top of the jutting break-card in the left hand.

Step Three: Next, with your right hand, lift the entire deck from your left hand to prepare to overhand shuffle back into the left hand. But first press your right thumb against the jutting break-card (now located approximately in the middle of the deck) with an upward pressure while squaring that break-card against the rear of the deck. You will create a slight gap (about a thirty-second of an inch wide) at the rear of the deck. Figure 14 shows that gap slightly exaggerated for illustrative purposes.

The gap will appear only at the rear of the deck and should extend no more than an inch or so along the length of the deck. Be sure your right forefinger extends across the top of the deck shielding the gap from opponents as shown in Figure 14 (in the photograph, the deck is angled for illustrative purposes so that you can view the otherwise hidden gap).

Step Four: Now overhand shuffle the cards, a few at a time, from your right hand into your left hand, but only up to the gap. When you reach the gap (you will feel the gap with your right thumb), throw the remaining block of cards -- your stack -- in a single toss on top of the shuffled cards in your left hand. You now have your undisturbed stack back on top of the deck once again.

Practice that move for ten or fifteen minutes. Your gap will probably be too wide at first, so strive to narrow it. Practice the complete blind shuffle slowly at first, trying to develop a natural, unhesitating rhythm. During the first twenty minutes or so of practice, you will tend to hesitate while shuffling up to the gap. And you will probably stare at the cards, afraid of missing the gap and shuffling some cards off the stack. The right thumb, however, will quickly get the feel of the gap.

If during practice your fingers tend toward dryness and you find the cards slipping as you shuffle, try using a moistening preparation such as Sortkwik or Tacky Finger, which are inexpensive preparations used for billcounting and are available at most office supply stores.

Once your fingers become familiar with the jutting break-card and the gap, you will rarely have to look at the deck. Although glancing at the cards while shuffling is perfectly natural and does not cause suspicion, Neocheaters make the gap as small as possible, but allow enough of a gap to work smoothly. A thirty-second of an inch or less is good. To help determine how small you can make your gap and still work smoothly, turn the top card of the deck face up as you practice, and make certain that the same top card of your stack reappears each time the shuffle is completed.

When practicing the blind shuffle, do not gap the deck during the first twenty minutes of practice. After you get the feel of the break-card, start using the gap. Then begin gapping the deck every time. For variety, however, during every three or four blind shuffles you might use the jutting break-card only (without the gap) during the blind shuffle. Practice keeping at least half the deck intact by overhand shuffling only about half to a third of the deck from the bottom onto the jutting break-card.

Practice doing the blind shuffle strictly by feel when you are watching television or at other idle times. Rhythm is more important than speed; you will gain speed naturally with practice. This shuffle can be done slowly, and it will look convincing as long as it is done smoothly and without hesitation, especially when creating the gap.

After an hour of practice, this maneuver becomes so easy and routine that you will be blind shuffling with fair smoothness and steadiness. In two to three hours, blind shuffling becomes second nature. It is that simple. Done correctly, the deck appears to be thoroughly shuffled. And when the blind shuffle is done in conjunction with the false riffle and false cut (described later in this chapter), you can convince even the most alert players that the deck has been thoroughly mixed.

Using that basic blind shuffle and a simple false cut (described later), even neophytes can shuffle their cards and then deal themselves prestacked four aces or straight flushes to everyone's astonishment. No one questions that the cards have been thoroughly shuffled. And no one can imagine how a prestacked deck could survive such shuffling.

Even a beginner can cull four aces or four kings using the simple discard-culling technique described in the previous chapter. He can then give the deck several rapid blind shuffles, a false cut, and triumphantly toss four aces off the top of the deck to the astonishment of all observers. Moreover, beginners need to master nothing more than a preliminary discard-stacking technique and the blind shuffle, plus have some knowledge about Neocheating to win in almost any game.

Let us assume you have spent at least an hour or two practicing the blind shuffle and can now perform it fairly easily. To test its effectiveness, pick up someone else's deck. Fan the first three or four cards, face down, and pretend to study the designs on their backs for about ten seconds. Frown as you study the cards, as though something were suspicious. Then turn the cards face up and glance at them to quickly memorize the cards in their proper sequence before turning them face down again. Forget the suits; they are unimportant. Square the cards together in your right hand and then fan the next three or four cards face down. Again, study their designs for a few moments and then, in a quick glance, memorize those cards in sequence. During this ruse, glance at the cards as briefly as possible -- as if confirming something you have seen in the designs on their backs. Rapidly square this next batch of memorized cards beneath the first memorized batch in your right hand.

You might be able to fan and memorize another batch of cards. Many people, however, have trouble memorizing more than six or seven digits. But after a little practice, most people can learn to easily remember nine or ten digits. Still, no more than six or seven memorized cards are necessary to make this ruse convincing. Constantly repeat in your mind the numbers in groups of three or four at a time as you shuffle. Now put the memorized cards back on top of the deck in your left hand. The memorized top cards may be, for example, Q-6-2-A-5-10-J -- you need to memorize only their initials. Next proceed to blind shuffle several times, explaining as you shuffle that imperfections in the manufacturer's design exist as tiny flaws that are consistent in every deck of that particular brand. Talk also serves as a minor distraction from the shuffle; although if you can blind shuffle with even minimum competence, you can perform in total silence in a filled amphitheatre without anyone knowing that you are blind shuffling.

If you think experienced cardplayers will not believe a story about visible imperfections on the backs of cards, proceed as follows: When you have finished your blind shuffles, slap the deck gently onto the table (creating an air of finality; rarely will anyone ask to cut the cards when you do that, especially if you do not hesitate and proceed immediately), lean close to the cards and "read" them from their backs, one by one. Take your time before calling and turning each card -- four or five seconds is about right. Peer intently at the backs of the cards before calling them, and then note your viewers' reactions. By the time you have "read" the fifth or sixth card, your audience will be studying the backs of the called cards. You can send experienced cardplayers on long searches for "legal" marks on cards. Ironically, they will often find such marks and imperfections, especially in cheaper brands of cards, that will actually let them read the backs of certain cards.

Professional cheaters scoff at such pointless ruses. (If no profit exists, why bother?) But those ruses demonstrate the power of the blind shuffle. And beginners can use ruses for practice and to build confidence before actually Neocheating for money. Be certain your blind shuffles are smooth before you attempt such demonstrations. Combined with the false cut described later in this chapter, the effect is spectacular.

You must always be aware of the number of cards in the stack. If a Neocheater stacks aces back-to-back for stud poker in a six-handed game, he worries only about keeping the top twelve cards of the deck intact. If he has stacked four of a kind in a six-handed game, then he must keep twenty-four cards unshuffled. And if he has stacked a pat hand or a wheel in lowball, he then has thirty cards in his stack -- more than half the deck for a six-handed game.... Professionals seldom stack straights or flushes in draw because of the number of cards involved. Why stack five-card pat hands when four of a kind is easier to stack.[ 17 ]

In any case, when stacking pat hands, you must keep up to two-thirds of the deck intact. That is, you actually shuffle only the bottom third or so of the deck. Do not worry about appearances; if your blind shuffle is smooth, the cards will seem mixed beyond suspicion.

The false riffle shuffle is nearly as effective as the blind shuffle and is necessary for certain kinds of culling and stacking taught in the next chapter. Moreover, the false riffle is easy to learn:

The deck is stacked. Now, handle the deck in the same way described for culling an ace in Chapter II. That is, place the thumb and two center fingers of the right hand at opposite ends of the deck while knuckling the forefinger down on top. Riffle-part the end of the deck with your thumb as shown in Figure 1A on page 25. But before reaching the halfway mark, stop riffling and pass the lower portion of the parted deck to your left hand. Now begin a riffle interlacing of the cards, but riffle the cards in your left hand much more rapidly than those in your right hand, and retain the top card in your left hand with your left thumb. At that stage you should still have a block of about fifteen or so cards in your right hand that are unshuffled (your stack). Smoothly and rapidly drop that entire block on top of the interlaced portion and then, without hesitation, drop the card retained by your left thumb on top of your intact stack as shown in Figure 15. (The retained card -- the ace -- is deliberately flashed for illustrative purposes . . . Neocheaters normally do not flash cards.) Immediately push the halves together and square the deck.

Practice this riffle shuffle repeatedly, getting the feel of that single card retained by your left thumb, and quickly dropping that card at the last moment to complete the riffle. Later, you will learn a refined version of the false riffle that looks considerably smoother,[ 18 ] but you must first perform this basic false riffle with ease.

After each riffle shuffle, you will have one extra card on top of the deck -- on top of the unshuffled block of cards that is your stack. (Eventually, you will be able to leave at least half the deck unshuffled this way, but do not attempt manipulating large stacks at this stage.) Treatment of those extra cards accumulated on top by false riffling will be discussed shortly.

Perform the riffle shuffle with rapidity. Unlike the blind shuffle, never try the riffle shuffle slowly. And although the movements may feel awkward at first, the shuffle does not appear awkward to other players. After only a few minutes of practice you will develop enough speed to increase the number of unshuffled cards until you can keep half the deck or more intact while riffle shuffling.

To preserve, for example, a four-of-a-kind stack in a seven-handed game, part and then pass only about a third of the deck to your left hand for riffle shuffling. Then interlace all but the top card in your left hand with only the bottom third or so of the cards in your right hand. Now drop the entire batch of cards retained in your right hand (which contains your undisturbed stack) on top of the interlaced cards and then immediately drop the final, single card retained by your left thumb. You will now have your stack preserved one card below the top of the deck.

Suppose you do the false riffle shuffle four times. You will then have four extra cards to remove from the top of your stack. The simplest method to remove those cards is to blind shuffle. So proceed with the blind shuffle (as described earlier in this chapter) by placing the squared, riffle-shuffled deck in your left hand and pulling out about a third of the cards from the lower portion of the deck with your right hand. Now with your left thumb, pull the top card from your right hand back onto the left-hand portion and jut that top card slightly. Next, overhand shuffle all the other cards in your right hand onto the cards in your left hand. The break-card is jutting out from the rear of the deck four cards above your stack. With your right hand, pull out all the cards up to the break-card and then with your left thumb, slide off (overhand shuffle) those four extra cards from the top of your stack very rapidly, one by one, back into your left hand. Then toss in a single block all the remaining cards in your right hand on top of the deck portion in your left hand and quickly follow with another complete blind shuffle.

To facilitate running the cards one by one, spend five minutes running through the entire deck with your left thumb slipping the cards off one at a time as quickly as possible.

In many games, the blind shuffle and the false cut are sufficient tools for the Neocheater. But the false riffle is indispensable to the Neocheater using the stacking techniques described in the next chapter.

With your undisturbed stack resting on top of a "thoroughly shuffled" deck, you then want to execute a legitimate-appearing cut that leaves your stack intact. To accomplish that, grasp the deck with both hands at opposite ends with the thumbs and index fingers (or middle fingers) as shown in Figure 16. Now while looking at Figures 16-18, execute this false cut by first pulling out about a third of the deck from the bottom with your right thumb and index finger and place those cards on top of the deck portion held by your left thumb and index finger (but retain your grip on the block of cards in your right hand). Then as shown in Figure 17, grasp the upper half of the cards held by your left hand with part of your right thumb and right middle finger while simultaneously releasing your left thumb and index finger from that same block of cards. At that brief moment, the deck will be split into three separate blocks, your right thumb and index and middle fingers gripping the two upper blocks while the left thumb and middle finger grips the bottom portion as shown in Figure 17.

Instantly release the uppermost block from your right index finger and thumb, at the same time pulling outward and slightly upward the two other blocks beneath held by your right and left hands. Each hand will be grasping about a third of the deck as you do this, and the top portion will now fall through the other two blocks of cards onto the table. You may use your right index finger to help guide the right-hand portion of loose cards as they fall to the table.

Next, with a slow smooth motion, slap the portion of the deck in your left hand onto those loose cards now on the table as shown in Figure 18. Then place the remaining cards (your stack) in your right hand on top of those cards and square the deck. Again, your stack sits undisturbed on top. Executed with any degree of smoothness, the cut looks very thorough and legitimate.

A mirror to view your motions is helpful for practice. For the best effect, you should perform the cut fairly rapidly, but slow down to place the two remaining blocks of cards from your left and right hands on top of the portion that falls to the table. Your stack will end up intact on top of the deck.

After thirty minutes of practice, you can execute this cut fairly smoothly. Remember to angle the card-blocks in your right and left hands in a slight upward sweeping motion as the top block falls between them. Strive for gracefulness. Again, the first phase of this cut, including dropping the top block between the other two portions in your hands, should be done fairly fast. But the final phase, which completes the cut by placing the other two blocks of cards on top, should be done more slowly.

More false cuts are described later in this book. But learn this basic standby cut first. The cut need not be done perfectly to be effective. And even if the cards tend to spread somewhat when they are dropped, do the cut without hesitation.

The three basic techniques in this chapter -- blind shuffling, false riffling, and false cutting -- are invaluable to the Neocheater. He uses those techniques constantly. With only a few hours practice, each technique quickly becomes habit, performed routinely without groping or thinking.

The blind shuffle will usually dispel any suspicion of cheating or stacking. For example, when cutting an ace for high card, a Neocheater culls an ace to the top of the deck in one riffle shuffle; he then blind shuffles the deck four or five times, runs the ace to the bottom in one overhand shuffle, crimps the lower deck, gives it two or three rapid center cuts and then a final bottom cut before slapping the deck on the table. ... The deck now appears thoroughly shuffled and cut.

The blind shuffle is more convincing than the false riffle. And when the blind shuffle is combined with the false cut, the illusion is deadly. In certain games, Neocheaters will not even need to offer the deck for a cut, and rarely will anyone request a cut if the Neocheater executes the blind shuffle and false cut with any degree of smoothness.

The Neocheater discard stacks himself aces back-to-back for stud poker, knows everyone's hole card, thoroughly blind shuffles and false cuts the deck, and is ready to deal. But what if an opponent demands a cut? An easy and simple method often used by Neocheaters to foil an opponent's cut is described below. Other more sophisticated techniques for negating any cut are described in later chapters.

Before offering the deck for a cut, the Neocheater rapidly crimps the deck as he would for cutting an ace as described in Chapter II and illustrated in Figures 4 and 5. He crimps by pushing downward and inward the bottom corner of the deck with his right thumb. Now with the stack on top, he quickly cuts the deck and then extends the crimped and squared deck to the player on his right for his cut. If that player cuts at the crimp, the stacked cards will end up right back on top of the deck, ready for dealing.

Most players will cut at any crimp near the middle of the deck eighty per cent of the time. Their thumb and fingers automatically go to the crimp four out of five times, even though they are unaware of the gap. The crimp is slight, and it is extremely unlikely that anyone would notice the gap. Even if the gap were noticed, few would consider it unusual since many players, especially chronic losers, bend and punish cards violently during the course of play as though the cards were mortal enemies.

The player on the right will occasionally miss the crimp, although the odds are well in the Neocheater's favor. But the professional accepts this vicissitude. Or he can use one of the advanced techniques (taught in Chapter VI) for foiling the cut. Those techniques do not depend on opponents cutting at the crimp. In any case, the professional makes a habit of noticing at what position the player on his right habitually cuts the deck -- near the top, middle, or roughly the three-quarter mark. He then places the crimp accordingly. Most players unthinkingly cut the deck at the approximate center. If the player on the right consistently cuts at the ends of the deck instead of the sides, the Neocheater simply crimps at the ends, using the end-crimping technique described in Chapter II and illustrated in Figures 7 and 8.

The crimp used for high-card cutting (as described in Chapter II) is gapped on only one side of the deck. In the course of a game, however, as opposed to high-card cutting, players are less alert to the cutting process, and your crimp will usually be more effective if it exists on both sides of the deck. Crimping both sides of the deck is described below:

First, crimp as you would when cutting for an ace, but instead of bending the lower left corner of the deck with your right thumb as described in Chapter II, push down with your right thumb at the center of the lower rear end of the deck. That will cause both sides of the deck to gap. Too much pressure from the thumb, however, will create a glaring crimp.

Some professionals use "agents" (other players working in collusion) who sit to their right. They will cut at the dealer's crimp every time or use a convincing false cut (such as the three-way false cut described on pages 66-70) that leaves the stack intact. The colluding partners also use a variety of other techniques to drain opponents of their money; those tactics will be covered in Chapter VII. This book, however, primarily teaches the lethal techniques of Neocheating -- techniques increasingly used by ordinary people who walk into games on their own and walk away with stuffed wallets, without ever using confederates, marked cards, or artificial and dangerous devices. But for the sake of comprehensiveness, all cheating methods and contrivances will be identified in later chapters.

A Neocheater's effectiveness and margin of safety lies in his own ten fingers. Anyone who can perform the maneuvers described up to this point with a degree of smoothness is already on par with most working professionals. Now you are ready for the stacking techniques covered in the next chapter. None are exceptionally difficult, two are relatively easy, and all are based primarily on techniques you already know.

[ 17 ] In any case, a Neocheater will seldom stack such powerful sure-thing hands because they are less profitable in the long run, as explained in Chapter XI.

[ 18 ] That version of riffle shuffling is called the Las Vegas Variation (it is the shuffle used by dealers in the Las Vegas casinos). As described in Chapter V, the deck in the Las Vegas Variation is completely shielded by the hands during the riffle shuffle.

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com