Suppose you are playing stud poker, and the player on your left seems to be winning too consistently whenever he deals. But the deck seems free of marks or gaffs; he is not using a shiner; and after careful observation you conclude that he is using Neocheating techniques to stack the deck. Moreover, you have been unconsciously cutting at his crimp. Yet, you cannot actually see him cheat. What should you do?

First, you could openly accuse him of cheating. But since you have no direct proof, accusing him may be the worst option. If, for example, you publicly revealed his subtle techniques, you could become suspect as being "too knowledgeable about cheating", thus tainting your reputation and perhaps even threatening your tenure in that game, especially if you are a consistent winner. Also, accusing the cheater could be risky, especially if you do not know how he will react. He may try to deflect the accusation by acrimoniously accusing you of cheating. Or he may try to bury the accusation by attacking you (even physically attacking you) for "questioning his honesty" or "besmirching his reputation". ... Accusing anyone of cheating without direct proof is risky business.

A player using Neocheating techniques to stack the deck is always safe --you cannot catch him in the act or prove his cheating. You may not like the way someone shuffles or riffles, or the way he cuts the deck, but that is his individual prerogative and cannot be the basis for an accusation. In fact, when it comes to shuffling and dealing, many innocent players look far more suspicious than most cheaters. A Neocheater's movements are natural; his methods are designed to allay suspicion. Moreover, many impeccably honest and experienced cardplayers know nothing about stacking or crimping, yet they shuffle and riffle the cards with very suspicious maneuvers: clumsily squaring the deck with the cards flat on the table facing them, shuffling the deck with mechanical and laborious motions, sifting awkwardly through discards, even riffling the cards face up.

A better move against the Neocheater is simply to miss his crimp by inconsistently cutting the deck extremely high or low. (For defense or counterattack purposes, try to sit on the immediate right of a suspected cheater so you can control the cut.) That would ensure a fair game and cause mounting frustration for the cheater, who would sooner or later realize the futility of further stacking. You could also destroy his stack by pulling a block of cards from the center of the deck, placing those cards on top, and then executing a regular cut.

Missing the crimp by purposely cutting very high or very low has a cat-and-mouse effect since the cheater will not be certain that you suspect him. Initially at least, he will probably classify you as one of those annoyingly erratic types who cannot decide where to cut next. He may try to change seats. Or he may simply give up his stacking efforts as long as you remain seated on his right.

Leaving the game is another way of responding to cheating. In fact, most "authorities" on cheating advise that the best course is to promptly leave any game in which you suspect or detect cheating. Following that advice is generally the least profitable route. Although in a few situations such as identified in Chapter I and XI, leaving is the only choice. But usually such action is unnecessary since the cheater can almost always be foiled and often be soundly beaten.

The above example of foiling the cheater is the simplest way to counter him. Below is a more profitable way to counter him. And Part Two of this book (DEFENSES AND COUNTERATTACKS) presents a full array of techniques designed to nullify, counter, and beat all cheaters.

With the special cut you can turn a cheater's stacking efforts to your advantage. Sit to the immediate right of the suspected cheater and deliberately cut at the crimp, restoring the deck to his stack. But then give the deck an additional, rapid single-card cut (the special cut), and you will get the dealer's stacked hand. The cheating dealer may not know exactly what you have done. And since the special cut looks like a normal center cut when executed swiftly, he will assume his stack was destroyed during that extra cut. The cheater will then be surprised and confused when you get his stacked hand. But because he knows that you did originally cut at or near his crimp, he will probably doggedly stack the deck another time or two until he realizes that you are not only aware of his cheating, but are taking advantage of him. At that point, he may leave the game, frustrated and outsmarted.

But beware of the extra alert cheater who knows the special cut. If he anticipates a repeat of that one-card cut the next time he deals, he can simply set you up for a big loss by adjusting his stack so you will cut yourself powerful cards while leaving him or a collusion partner with even more powerful cards.

The special cut is easy and takes about an hour of practice to perform smoothly. The major function of the cut is to remove the top card from the stack, while leaving the rest of the stack intact on top of the deck. Thus if you are sitting to the right of the dealer and remove the top card from his stack, you will receive any hand that he has stacked for himself.

Also, the special cut is ideal for removing an extra card from your own stack -- such as removing the extra card placed there by a false riffle (as described on page 88). Moreover, the special cut is an excellent follow-up to the false riffle and is much faster than blind shuffles that are normally used to remove extra cards.

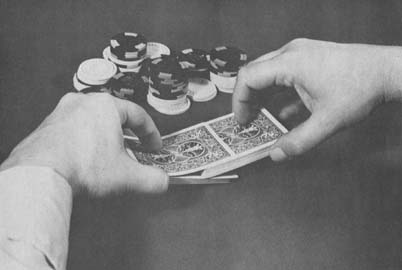

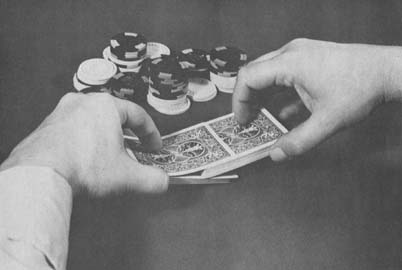

To perform the special one-card cut, first pick up the deck with your left hand. Then referring to Figure 23, use both hands to grasp the deck. Grasp each end between the thumbs and middle and ring fingers. The forefingers (index fingers) of each hand are positioned on the top card, but the left finger presses firmly down, while the right forefinger rests loosely. Also the left ring finger grips the bottom half of the deck while the left middle finger is held loosely.

Now, grasping the upper half of the deck with the right middle finger and thumb, smoothly pull that portion of the deck out with a straight sliding motion as the left forefinger exerts pressure to hold back the top card as shown in Figure 23. Now drop the left-hand portion of the deck with that retained top card onto the table and complete the cut by slapping the right hand cards gently on top of those just dropped on the table. Then square the deck.

Rapidly executed, the special cut gives the appearance of a normal center cut. When practicing the special cut, note that the deck is gripped by the left hand at the bottom half mainly with the thumb and left ring finger. With the right hand, tilt the block of cards slightly upward while pulling them from beneath the single top card retained by the left forefinger. The right forefinger should exert no pressure against the top card so as not to hinder its retention in the left hand.

When using this cut for your own stack (e.g., to get rid of an extra top card left there by a false riffle), keep in mind the number of cards in your stack. If, for example, you have stacked a pat hand in a six-handed game, you must then control the top thirty cards of the deck by pulling out at least thirty cards with your right hand (or else the top card of the deck retained by your left forefinger will end up in the stacked portion, damaging the stack). But normally, unless you are stacking pat hands, you can routinely pull out about half the deck without disturbing the stack when executing the special cut.

The next false cut looks incredibly thorough, but leaves the stack completely intact and is nothing more than an elaborate extension of the basic false cut taught in Chapter IV.

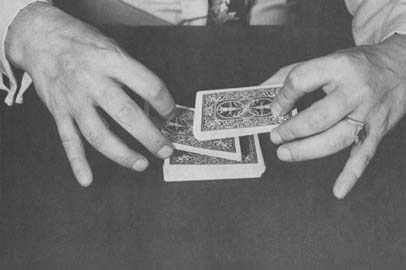

To help visualize the finger positions for this cut, refer to Figure 24 which shows the four-block cut in its final stages. Begin practicing this cut by first holding the full deck with your left two center fingers and thumb along the sides, near the end. Hold the left forefinger out slightly, not touching the cards. Next, grasp about a fourth of the deck from the bottom with your right forefinger and thumb, pull out that block of cards and place it over the top of the deck -- but continue holding the right-hand end of those cards about a quarter of an inch above the deck. Now separate (roughly in half) the lower block of cards in your left hand by parting your left middle and ring fingers about a half an inch. The side of the deck gripped by your left thumb will remain solidly together.

Then your right middle finger (or ring finger, if easier) and your right thumb dip down and seize about half of that bottom, split portion of the deck. But at the same time, your right thumb and index finger retain their grip on the topmost block of cards. As shown in Figure 24, the right thumb and middle finger then partially withdraw (about two inches) that lower block of cards along with the upper block. At that juncture, each hand holds two separate blocks of cards, parted but not completely separated from the deck (as shown in Figure 24).

Both hands now tilt upward slightly and the right index finger and thumb release only the top block of cards as both hands part to let that top block fall through to the table. (This upward V-angled parting motion is similar to that used in the basic three-block false cut described on page 66.)

Now drop the bottom block of cards in the left hand on top of those cards on the table. Then drop the remaining block of cards in the right hand, and finally drop the last block of cards still in the left hand as shown in Figure 25. ... Your stack remains on top, completely intact despite an incredibly thorough-looking cut.

Like many Neocheating maneuvers, the description seems much more intricate than the actual execution. The entire four-block false cut takes no more than five or six seconds to execute, even when done without haste. The moves are relatively easy to execute, especially if you have practiced the three-block cut described in Chapter IV. And, as in that three-block cut, the first step of bringing the bottom portion of cards to the top is performed faster than the subsequent card-dropping steps. After an hour or two of practice, you will be executing the four-block cut smoothly. And if you decide to master this cut, you will develop a nimbleness in your fingers that will be valuable for executing almost any card-manipulation technique.

The intricate-appearing, four-block false cut adds a convincing finality to any stacking procedure. But against certain opponents (e.g., against very naive or against very savvy opponents), extra thorough or elaborate cuts may actually increase suspicion. In such cases, a simpler or more straight forward cut is best.

The next false cut is neither as complex nor as flourishing as the one above. Instead, the cut has a crisp businesslike appearance and is worth mastering for both its simplicity and efficacy.

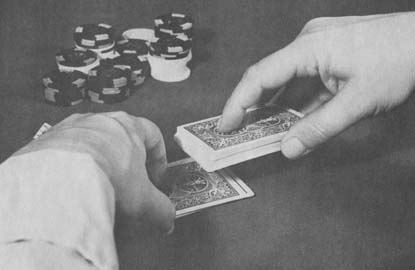

Lift the deck from the table and grasp the cards with both hands by placing the thumbs and middle fingers along the sides at each end and resting the forefingers lightly on top. Next, create a slender gap along the inner side of the deck (as shown in Figure 26-A) by pushing down (crimping) the right inside corners of the bottom few cards with your right thumb; and then with your right thumb and middle finger pull out about half of the lower deck and place that crimped portion on top of the other deck half. The exposed side of the deck facing opponents should be even, with no visible gaps. The right fingers shield the gap on the right end, and the right forefinger pressing down on top of the deck keeps the gap from being visible along the inside edge and on the left end.

With the left thumb and middle finger, proceed with a series of shallow cuts by pulling small blocks of cards from the top and placing them one above the other on the table as shown in Figure 26-B. When you approach the gap let it open wider by releasing the pressure from your right forefinger (which has been pressing down on top of the deck) -- with the wider gap you can more easily and accurately hit your crimp. Continue pulling off small blocks of cards up to that crimp. Then with an air of finality slap the remaining entire block of cards on top of those already on the table. ... Your stack now sits undisturbed on top. Square the deck on the table with your thumbs and fingers.

In thirty minutes to an hour, you should be able to execute this basic false cut with speed and smoothness. The series of small-block cuts should be fairly rapid and without hesitation, especially when you reach the gap.

The basic workhorse cut is popular among clever mechanics and, for the Neocheater, is well worth mastering. Also, this false cut can preserve a bottom cull or stack by making the first cut up to the gap, followed by a series of small-block cuts with the remainder of the deck.

Detect false cuts by:

Defend against false cuts by:

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com