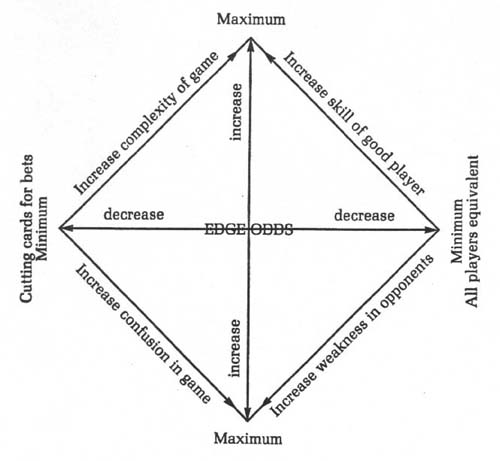

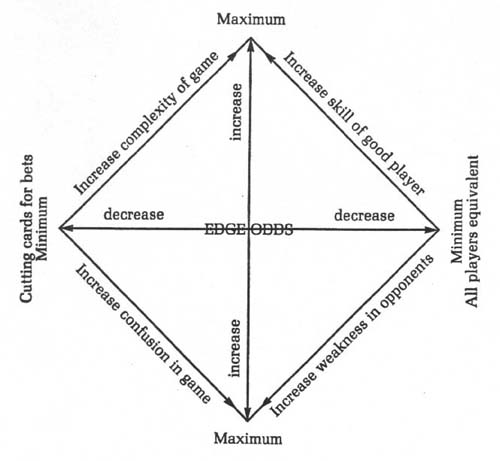

How far does John Finn go toward completing the Diamond? How much further could he increase his edge odds in the Monday night game? He makes the following estimations:

| Side of Diamond | % Completed | Maximum Possible % | Limitation |

| Increase skill of good player | 95 | 100 | None |

| Increase weakness in opponents | 45 | 65 | Availability of weak players capable of large losses |

| Increase confusion in game | 70 | 80 | Human tolerance |

| Increase complexity of game | 90 | 95 | Opponents' capacity to comprehend |

| Total (average), % | ___ 75 | ___ 85 |

Playing with the Diamond 75 percent complete, John's edge odds are about 65 percent. He estimates that under the best conditions, the Diamond would be 85 percent complete, and thus his edge odds could improve to a maximum of 74 percent. That estimation of maximum edge odds establishes a goal toward which John Finn can strive.

The good poker player directs his actions toward achieving maximum advantages while preventing his opponents from realizing that he is motivated entirely by profit. He is a winner acting like a loser.

While playing his hand, the good player is seldom an actor. Instead he practices a bland behavior that--

A good player never loses interest in his hand until the moment he folds. If opponents can sense his intention to fold before his turn, they will become more defensive when he does hold a playable hand, thus decreasing his edge odds.

Improvised acting while playing a hand is usually ineffective because the act does not develop from a well-planned basis. Yet when not involved in the action, the good player has many opportunities to act effectively on a carefully planned basis. Occasionally while playing in a hand, he deviates from his systemized behavior when he knows a certain behavior will cause an opponent to make a desired move (call, drop, bet, or raise).

"What's John doing now?" Scotty Nichols whines. He rubs his whiskered face while wondering if he should call John's $50 raise. "Can't ever read him."

"That's 'cause he sits like a tree stump," Quintin Merck says. "Gives you nothing to grab. You guys that act are easy to read."

John Finn will act, however, when he is reasonably certain of his opponents' reactions. Consider that hand in which he is supposedly sitting like the tree stump:

Wanting Scotty to call, John lets his fingers creep into the pot and spread out the money. He pulls out the big bills and lays them on top. Scotty stares at the money; he is a loser, and winning that pot would make him even . . . he licks his lips and calls.

Poor Scotty never should have called. His kings-up two pair were no match for John's full house. Was John acting? Yes, because Scotty was undecided and John varied his own behavior to make him call. John also did some long-range acting toward Quintin Merck. How was that? Quintin observed John's maneuver to make Scotty call. John heard Quintin snort when Scotty fell into the trap.

The following week, John and Quintin are battling for a large pot. John raises . . . Quintin scratches his head and then starts to call. John's fingers creep into the pot and spread out the money. He pulls out the big bills and lays them on top. Quintin snorts, shows his three deuces to everyone, and then folds with a prissy smile. His smile snaps into a frown when John throws his hand face up on the table. His hand this time? A four flush.

Why did Quintin fall into that trap? He forgot that John would not apply the same tactic toward a poor player like Scotty as he would toward a sound player like Quintin. John plays against the individual as well as the situation.

a. Unfriendly or Intimidating (40)

In public (club or casino) games or in games consisting mostly of professionals or strangers, tough or unfriendly and intimidating behavior may be best. Such behavior disorients opponents ... and disoriented players are easier to control. Unfriendly behavior irritates opponents, causing them to act more emotionally and to play poorer poker.

The following unfriendly and intimidating behavior can be advantageously practiced by the good player:

Planned unfriendly or intimidating behavior can be effective for increasing edge odds and for controlling opponents. Still, the good player uses caution when being unfriendly. He analyzes the game and evaluates the effects of any behavior on both his short-term and long-term profits.

In some games, intimidating behavior is tolerated if a little humor or congenial behavior is blended in. Also, the good player may adopt a split personality or may be unfriendly to certain players and congenial to others ... whatever is most advantageous.

b. Congenial (41)

Unfriendly and intimidating behavior is undesirable for most friendly or regular private games. Unpleasant behavior could break up the game, result in expulsion from the game, or cause valuable losers to quit. Congenial behavior is often necessary in such games. But most friendly traditions are disadvantageous to the good player, such as--

Occasional but dramatic displays of friendly traditions will usually satisfy the other players.

Sometimes John Finn is the most congenial player in the game. At other times, he is not so congenial. He always behaves in a way that offers him the greatest advantages.

How can John switch his personality to fit the game? He keeps himself free from emotional ties to the game and the players. That allows him to think objectively and define what behavior offers the most advantage. For example, he will drive a good player out of the game with unfriendly behavior (see Concept 108). Why will he do that? Another good player would increase the financial strain on the losers, which in turn would cost John some of his profits to keep those losers in the game. In other words, a good player would cost John money . . . so why let him play? Why not replace him with a more profitable, poor player?

c. Introvert and extrovert (42)

The good player usually behaves oppositely to the general behavior of his opponents. For example, in a quiet game with serious players, an extroverted personality may be advantageous. In a wild or boisterous game, an introverted personality is often the most advantageous.

The extent of introverted or extroverted behavior that John Finn assumes depends on the game, as shown below:

| Game | Players' Behavior | Advantageous Behavior (John Finn 's Behavior) |

| Monday | Mixed | Ambiverted |

| Tuesday | Introverted | Extroverted |

| Thursday | Ambiverted | Ambiverted |

| Friday | Extroverted | Introverted |

a. Concealing desires (44)

To keep his opponents off guard, the good player conceals his desires, as shown in Table 18.

| Desire | Method to Conceal |

| More weak players | Never discuss weaknesses of players. |

| Faster betting pace | Increase betting pace without verbally expressing a desire for a faster betting pace. Occasionally complain about the fast pace and wild modifications. |

| Higher stakes | Never suggest higher stakes unless chances for an increase are nearly certain, then suggest higher stakes as a way to give losers a break or to make the betting more equitable. |

| More games | Never reveal activities in other games. Organize games without expressing an eagerness to play. |

b. Concealing facts(45)

The good player conceals facts to avoid arousing unfavorable suspicions, as shown in Table 19.

| Facts | Methods to Conceal |

| Easiness of game | Never mention the poor quality of poker played in any game. Praise "skills" of opponents, especially of poor players. |

| Winnings | Never discuss personal winnings. After each game, report less than actual winnings or more than actual losses. But exaggerate only to a believable extent. Never reveal long-term winnings. Conceal affluence by driving an old car to the game. |

| Tight play | Fold cards without comment or excuses. Make loose-appearing or wild plays whenever investment odds are favorable. |

| Good play | Never explain the true strategy behind a play. Instead, give erroneous reasoning for strategy. Never brag . . . downgrade own performance. |

| Control over game | Assume a humble but assertive attitude. |

To turn attention away from his poker success, the good player praises and exaggerates the poker ability of other winners. In a verbal smoke screen, he discusses and magnifies everyone's winnings except his own. When losing, the good player complains about the tough game and exaggerates his losses. But he never mentions the losses of other players.

c. Lying (46)

Lying is a key tool of strategy. For example, when asked about his folded cards, the good player lies about them to create the impression that he plays loosely or poorly. To lie effectively, he must always lie within believable boundaries to keep others from automatically doubting him.

With careful lying and calculated deceit, John Finn builds his image as a kind-hearted, loose player who is an asset to the game. Here is an example of how he builds this advantageous image:

The game is highball draw with a twist. John begins with a pair of aces, draws three cards, and ends up with two pair. During the betting, he notices Ted Fehr putting $25 too much into the pot. John says nothing and plays his two pair pat on the twist. Sid Bennett misses his flush and folds out of turn . . . that out-of-turn fold is very helpful to John.

Now with only two remaining in the hand, Ted bets $25. John reads him for trips and reasons Ted's bet like this: Ted thinks his three of a kind are beat by John's pat hand. So if he checks, John will bet the $50 maximum, and he will have to call. By making a smaller bet, he hopes that John will only call, thus saving him $25. Ted's strategy backfires . . . John raises to $75.

"How many cards did you draw in the first round?" Ted asks.

"One," John quickly lies.

"A one-card draw, then pat on the twist ... I can't call that," Ted sighs while folding his cards.

John places his cards face-down next to Sid's dead hand.

"What'd you have, the straight or flush?" Ted asks.

John pulls in the pot. He then picks up Sid's cards, gives them to Ted, and says in a low voice, "Don't tell anyone my hand."

"What!" Ted cries on seeing the cards. "You play a four flush pat to win a three-hundred-dollar pot?" John smiles and nods. Ted slumps in his chair.

"That's what I like," Sid says. "His wild playing beats all you tight players.... You're great, John."

John shrugs his shoulders and then throws $25 to Ted.

"What's this for?" Ted asks.

"Your last bet," John says "I don't feel right about taking it."

"Merciful guy." Ted smiles. Then, counting the money, he continues, "You might win all my money, but you're still a gentleman."

"That's no gift," Quintin Merck mumbles, "Ted put . . .

"Whose deal?" John interrupts.... So besides winning a $300 pot, he did a lot of favorable image-building with that hand.

a. Carefree(48)

A carefree atmosphere stimulates a careless attitude about money and causes opponents to play poorer poker. A carefree atmosphere is developed by--

The good player himself is never carefree about poker or careless with money ... he always respects money. His careless behavior is a planned act.

b. Relaxed (49)

A relaxed atmosphere lulls opponents into decreased concentration, which diminishes their playing abilities and increases their readability. Contributing to a relaxed atmosphere are--

To maintain peak concentration, the good player denies himself the effects of comfort and relaxation.

c. Pleasant (50)

A pleasant atmosphere holds weak players in the game and attracts new players. The good player creates a pleasant atmosphere by--

Most players gain pleasure from feeling accepted and belonging to the group. But the good player gains pleasure from his ability to win money and control the game.

Whenever the Monday night game gets serious, the players think more clearly and make fewer mistakes. When serious, everyone plays tighter and is less prone to John Finn's influence. So he keeps the game carefree and careless by behavior such as described below:

A newcomer, playing in the high-stake Monday game for the first time, is nervous and is playing very tight. He shuffles . . . the cards spray from his trembling hands and scatter all over the floor. Finally he deals five-card stud. John gets a pair of aces on his first two up cards. Everyone drops out except big loser Scotty Nichols. "Haven't won a pot all night," he says and then gulps. "I ...I gotta win one." John makes a few small bets. Scotty stays to the end and loses with his wired pair of queens. The pot is small, containing perhaps $35.

With quivering lips, Scotty slowly turns his cards over. Suddenly John shoves the whole pot across the table and into Scotty's lap while laughing, "Don't be so miserable. It's only money.... Take it all."

The newcomer's mouth snaps open. "What a crazy game!" he exclaims. "I've never seen anything like that!"

Scotty grims and mumbles something about John's generous act.

"Help thy neighbor, help thy luck," John tells everyone. "Nothing is cheaper than money."

That move will be remembered and discussed for a long time. The cost to John: about $35. The return to John: certainly many times that.

a. Reading opponents (52)

All players have repeating habits and nervous patterns that give away their hands. The task of the good player is to find and interpret those patterns. Most poker players offer readable patterns (tells) in their--

Questions are potent tools for reading opponents' hands. Often players reveal their hands by impulsive responses to seemingly innocuous questions as--

Ways of looking at opponents are also important: The good player controls the position of his head and eyes to avoid a direct stare at those opponents who become cautious and less readable when feeling observed. He will, however, stare directly at those players who get nervous and more readable when feeling observed. In some games, especially public games, the good player may wear dark glasses to conceal his eye actions.

When involved in action, the good player reads his opponents and then makes his play accordingly. When not involved in the action, he analyzes all players for readable patterns. At the conclusion of each pot, he correlates all revealed hands to his observations. By that technique, he can discover and build an inventory of readable patterns for each opponent.

The most valuable pages in John's black leather notebook describe the readable patterns of his opponents. For example, consider his notes about Scotty Nichols:

Before hand--When winning, breaking even, or losing slightly, he plays very tight and never bluffs. Stays to end only when holding a strong hand. When losing heavily, he panics--he plays wildly while trying to bluff far too often. Once hooked in a hand, he stays to the end.

Receiving cards--Grabs for each dealt card when a good hand is developing. Casually looks at new cards when holding a poor-potential hand.

Dealing--Usually flashes bottom card when picking up the deck. Often flashes cards he deals to himself.

Looking at cards--When planning to play, he looks to his right. When planning to raise, he looks to his left. When planning to drop, he looks blankly into space.

Handling cards--Leaves cards on table when he intends to fold. If holding a playable pair, two pair, trips, a bobtail straight, or a full house, he arranges his cards and then does not disturb them. If holding a lowball hand or a four flush, he continuously ruffles the cards through his fingers.

Before bet--Touches his money lightly when going to call. His thumb lifts edge of money when going to raise. Picks up money when going to bluff. Does not touch money when going to fold.

Betting--Puts money in pot with a deliberate motion when not confident, with a flicking motion when confident, and with a hesitation followed by a flicking motion when sandbagging.

Raising--Cheek muscles flex when holding a certain winner. A stiffness develops around his upper lip when worried. Breathes through mouth when bluffing.

Drawing--Inserts cards randomly into his hand and then ruffles cards when drawing to a four flush or a pair. Puts cards on one end with no ruffling when drawing to a four straight or trips. Puts card second from the end when drawing to trips with a kicker. Puts card in center of hand when drawing to two pair. With two pair, he looks at draw quickly. With all other hands, he slowly squeezes cards open. Squeezes very slowly when drawing to lowball, flush, or straight hands. Jerks hand when he misses.

Looking at draw--Exhales when he misses, and his eyes stare blankly at the table. Inhales when he catches, and his eyes glance at his opponents and then at the pot.

Stud up cards--After catching a good card, he touches it first and then reorganizes his cards. Confirms catch by looking several times at his hole cards.

Stud hole cards--When hole cards are good, he keeps them neatly organized and touches them periodically. Does not bother to organize or touch poor cards. If one fakes a move to grab his hole cards, he impulsively jumps and grabs the cards if they are good . . . does nothing if they are poor.

Last-round bet--A quick call means he will call a raise. Picking up all his money when calling means he will not call a raise. Watching the next caller without looking directly at him means he is hoping for a raise.

Questions--"Do you have three tens beat?" Scotty blinks his eyes if his hand does not beat three tens ... no blinking if it does. "How many cards did you draw?" Scotty hesitates and turns eyes up in thought if he is bluffing. Gives a casual answer if holding a normal hand. Hesitates and stares at the pot if holding a powerful hand.

After hand--He will play carelessly when sulking over losses. He will play extra tight when winning and counting his money.

With so many readable patterns, Scotty has little chance against John Finn. By putting together several of those patterns, John reads him with consistent accuracy. And Scotty's low awareness level keeps him from recognizing the habits that reveal his cards and intentions.

John also has similar dossiers on the other players and can usually read them accurately ... even a sound player like Quintin Merck. Because of Quintin's greater awareness, he occasionally recognizes and eliminates a habit that reveals his hand. But John uses several habits to cross-check readable patterns and can quickly detect when anyone changes or eliminates a habit. After each game, he records in his notebook any new or changed habits.... John Finn knows that all players have telling habits and readable patterns that give away their hands and intentions. The task of the good player is to identify and interpret those habits and patterns so he can accurately read the hands and intentions of every opponent. Reading opponents' hands is much more effective than using marked cards and it is honest.

The question-type giveaways or tells are quite reliable and are particularly useful for pinpointing the exact value of an opponent's hand. For example, if John holds trips and reads his opponent for trips, he might use questions to find out who has the best hand. Excessive use of questions, however, can rouse suspicion and decrease the usefulness of question-and-answer tells.

b. Remembering exposed cards and ghost hands (53)

By remembering all exposed cards, a player increases his accuracy in estimating investment and card odds. In games with many players (eight or more), discarded and folded cards are often redealt. Knowledge of those cards can be crucial for estimating meaningful investment odds. In some games, discarded and folded cards are actually placed on the bottom of the deck without shuffling. (The good player encourages that practice.) If those cards are redealt during the late rounds, the good player will know what cards are to be dealt to whom . . . a huge advantage for the later rounds of big bets.

With disciplined concentration and practice, any player can learn to memorize all exposed cards. For the discipline value alone, remembering exposed cards is always a worthwhile effort. But many players excuse themselves from this chore by rationalizing that memorization of cards dissipates their concentration on the other aspects of the game. That may be true when a player first tries to memorize cards, but a disciplined training effort toward memorizing all exposed cards will ultimately increase his concentration powers in every area of poker.

Remembering the exposed draw hands or the order of exposed stud cards from the previous deal can bring financial rewards. Old hands often reappear on the next deal (ghost hands), especially when the shuffling is in complete (the good player encourages sloppy and incomplete shuffling). For example, a good player is sitting under the gun (on the dealer's left) and needs a king to fill his inside straight in five-card stud. But the last card dealt in that round (the dealer's card) is a king. The good player, rather than being discouraged, recalls that the winner of the previous hand held three kings. Since the deck had been poorly shuffled. the chances of the next card (his card) also being a king are good. Knowing this, he now has a strong betting advantage.

John Finn memorizes all exposed and flashed cards He mentally organizes every exposed stud card into one of the four following categories by saying to himself, for example, Sid's two of hearts would help--

That association of each card with a definite hand not only organizes John's thoughts but also aids his memory.

Now if Sid folds and his two of hearts is the first card to go on the bottom of the deck, John will remember that the fifty-third card is the two of hearts. Then by mentally counting the dealt cards, John will know when and to whom the two of hearts will be redealt. By that procedure, he often knows several cards that will be redealt. For example, he may know the fifty-third, fifty-fourth, fifty-seventh, sixtieth, and sixty-first card.... The cards he knows depends on how the folded cards are put on the bottom of the deck.

c. Seeing flashed cards (54)

Many important cards are flashed during a game. Players who see flashed cards are not cheating. Cheating occurs only through a deliberate physical action to see unexposed cards. For example, a player who is dealing and purposely turns the deck to look at the bottom card is cheating. But a player who sees cards flashed by someone else violates no rule or ethic. To see the maximum number of flashed cards. one must know when and where to expect them. When the mind is alert to flashing cards, the eye can be trained to spot and identify them. Cards often flash when--

The good player occasionally tells a player to hold back his cards or warns a dealer that he is flashing cards. He does that to create an image of honesty, which keeps opponents from suspecting his constant use of flashed cards. He knows his warnings have little permanent effect on stopping players from flashing cards. In fact, warned players often become more careless about flashing because of their increased confidence in the "honesty" of the game.

Using data from one hundred games, John Finn compiles the following chart, which illustrates the number of flashed cards he sees in the Monday night game:

| Identified per Hand [adjusted for a seven-man game] Draw | Identified per Hand [adjusted for a seven-man game] 7-Stud | |

| Dealer* | 6 | 2 |

| Active players | 7 | 1 |

| Kibitzers and peekers | 2 | 1 |

| Folded players | 9 | 3 |

| Total | ___ 24 | ___ 7 |

*Also, the bottom card of the deck is exposed 75 percent of the time.

These data show that in addition to seeing his own cards, John sees over half the deck in an average game of draw poker--just by keeping his eyes open. The limit he goes to see flashed cards is illustrated below:

Mike Bell is a new player. John does not yet know his habits and must rely on other tools to read him--such as seeing flashed cards.

The game is lowball draw with one twist. The betting is heavy, and the pot grows large. John has a fairly good hand (a seven low) and does not twist. Mike bets heavily and then draws one card. John figures he is drawing to a very good low hand, perhaps to a six low.

John bets. Ted Fehr pretends to have a good hand, but just calls--John reads him for a poor nine low. Everyone else folds except Mike Bell, who holds his cards close to his face and slowly squeezes them open; John studies Mike's face very closely. Actually he is not looking at his face, but is watching the reflection in his eyeglasses. When Mike opens his hand, John sees the scattered dots of low cards plus the massive design of a picture card reflecting in the glasses. (You never knew that?... Try it, especially if your bespectacled victim has a strong light directly over or behind his head. Occasionally a crucial card can even be identified in a player's bare eyeball.)

In trying to lure a bluff from the new player, John simply checks. Having already put $100 into the pot, Mike falls into the trap by making a $50 bluff bet. If John had not seen the reflection of a picture card in Mike's glasses, he might have folded. But now he not only calls the bluff bet with confidence, but tries a little experiment--he raises $1. Ted folds; and Mike, biting his lip after his bluff failure, falls into the trap again--he tries a desperate double bluff by raising $50. His error? He refuses to accept his first mistake and repeats his error.... Also, he holds cards too close to his glasses.

John calmly calls and raises another $1. Mike folds by ripping up his cards and throwing them all over the floor. His playing then disintegrates. What a valuable reflection, John says to himself.

[Note: Luring or eliciting bluffs and double bluffs from opponents is a major money-making strategy of the good player. In fact, in most games, he purposely lures other players into bluffing more often than he bluffs himself.]

d. Intentional flashing (55)

The good player intentionally flashes cards in his hand to cause opponents to drop, call, bet, raise, or bluff. But he uses the intentional flash with caution. If suspected, intentional flashes are less effective and can cause resentment among players.

After the final card of a seven-card stud game, John Finn holds a partly hidden flush--three clubs showing and two clubs in the hole. He also has a pair of jacks showing and a pair of sevens in the hole. Ted Fehr has the other pair of sevens showing, and John reads him for two pair-- queens over sevens. Sid Bennett has aces up and makes a $1 bet. Ted, betting strong from the start, raises $25. John just calls.

"I should raise," Sid thinks out loud as he strokes his chin. "John is weak ... probably has jacks up. But Ted might have three sevens . . . no other sevens are showing."

John picks up his hole cards, shifts his position and crosses his legs. Accidentally-on-purpose he turns his hand so Sid can see two of his hole cards--the pair of sevens.

"I'll raise to fifty dollars," Sid says and chuckles. He knows that John has two pair and that Ted cannot have three sevens. Never thinking that John might also have a flush, Sid looks pleased with his sharpness in spotting John's hole cards.

After Ted folds, John raises back. Sid calls and then slaps his hand against his massive forehead when John shows him a flush. He grumbles something about bad luck, never realizing the trap he was sucked into.

e. Peekers (56)

Spectators and players who have folded often peek at undealt cards or at hands of active players. Most peekers exhibit readable behavior patterns that give away the value of every card and every hand they look at. Those patterns are found in their--

Players who allow others to peek at their hands encounter problems of--

The good player carefully selects those whom he lets look at his hand. He lets certain players peek at his cards in order to--

The good player controls peeking by the following methods:

A new player, Charlie Holland, sits next to John Finn. Playing in his first big-stake game, Charlie is nervous and impressionable. John takes full advantage of this by using his peeking strategy to throw Charlie into permanent confusion

In a hand of lowball draw, John discards a king and draws a seven low. Charlie holds a pat nine low. John has lured him into calling a large first-round bet and two raises. In the last round, Sid makes a defensive $25 bet; Charlie calls. John raises to $75 and everyone folds. John throws his cards on top of his discarded king and then pulls in the pot.

"What'd you have?" Charlie asks.

"A fat king," John says, smiling as he picks up the cards and shows him the king.

Charlie Holland groans. With a drooping face, he stares at the large pot. "I should've called," he moans as John slowly pulls in the pot while laying the larger bills on top for better viewing.

What does this have to do with peeking? Nothing yet.... The next hand is seven-card stud. Charlie drops out early to study John's technique. He stretches his neck to peek at John's hole cards. With an air of friendship, John Finn loops his arm around Charlie's shoulder and shows him the hole cards--John has an ace-king diamond flush.

"We'll kill 'em with this ace-king diamond flush," John says loudly.

Surprised that John announced his exact hand, Charlie looks at the cards again, then replies, "Yeah, man!"

But actually, John is not confident of his flush because he reads both Ted and Quintin for two pair, and all eight of their full-house cards are alive. He figures the odds are about 1 in 2 that one of them will catch a full house. He also knows that they fear his flush and will not bet unless they catch the full house.

Scotty Nichols, who folded early, is sitting between Quintin and Ted. With his head bobbing back and forth, he peeks at their hands as they catch new cards. Now, the last hole card is dealt. John watches Scotty: First his plump head points toward the highest hand--Ted's queens over jacks. He peeks at Ted's new hole card; immediately his head snaps over to check Quintin's cards. Obviously Ted's new card is not very interesting ... he failed to catch his full house, John figures.

Now Scotty looks at Quintin's new card. He looks again and then glances at Quintin's up cards ... then checks the hole cards once again. Scotty does not say a word, but he may as well be yelling, "Interesting! A very interesting catch for the full house!"

Adjusting his thick glasses, Scotty next looks at John's up cards; his eyes then dart back and forth between Quintin and John while ignoring Ted's hand.

What happens? Ted foolishly bets $25. Quintin raises $1. Scotty covers his smiling mouth with his hand. Expecting some lively action, he waits for John to get sucked into Quintin's great trap. And across the table, Charlie Holland smiles; he waits for John to blast Quintin with a big raise. John Finn folds.

Charlie rises halfway out of his seat while making gurgling noises. "You .. you know what you dropped?" he stammers

"Yeah, a busted hand," John says, shrugging.

"A busted hand." Charlie bellows. His hand shoots to the table and grabs John's folded cards. "Look, you had an ace-king diamond flush. You even announced it!"

"Oh, no! I thought it was a four flush," John lies. Quintin glowers at John's flush and then shows his winning full house.... Charlie sits down talking to himself.

Alert playing not only saves John money, but confuses everyone and sets up Charlie for future control.

| Nongame Contact | Behavior |

| Friend of a player | Praise the player and his performance in poker. Stress the merits of the game. |

| Potential player | Suggest the easiness of winning money in the game. Stress the social and pleasant aspects of the game. |

| Player from another game | Indicate a desire to play in his game. Extend an invitation to your own game. Create an image of being a loose, sociable player. |

| Family of a player | Flatter poker skill of the player. If they complain about his losses, suggest that his bad luck is due to change. |

| Other acquaintances | Indicate a desire to play poker. Downgrade personal performance in poker ... talk about losses. |

Sometimes the good player practices contrasting game and nongame behavior. For example, if during the game he practices unfriendly behavior toward a certain opponent, he may find it advantageous to be congenial toward this same person outside the game.

Although all poker players in the Monday night game view themselves as independent men, some of their wives retain various degrees of control over them. John plans his behavior toward their wives according to the following notations in his notebook:

| Wife Summary | |

| Betty Nichols | Concerned about Scotty's losses. To calm her, recall his past winnings. She will not make him quit if reminded that poker keeps him from drinking. |

| Florence Merck | Supports Quintin's playing, especially since he is winning. |

| Stephanie Bennett | Thinks Sid is foolish for playing. Realizes he will never win and wants him to quit, but also realizes she has little control over him. Besides, having plenty of money, she is not too worried about his losses. |

| Rita Fehr | Does not care and makes no attempt to influence Ted, despite his suicidal losses. |

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com