| [Last] | [Contents] | [Next] |

We've seen that there are two kinds of thinking. Inductive thinking is the older kind, which we share with other animals. We need it to make sense of the layered patterns that fill the universe, and it is essential if we are going to advance science, produce art, program computers or manage businesses. Original stuff always comes from inductive thinking. Deductive thinking is the newer kind, peculiar to humans. We need it to test and clarify our understanding and work through the consequences of what we already know. It can help us identify flaws in our present understanding, showing us where we can make progress by doing more work. Humans are superior to other animals because we can do deductive reasoning, but we only make a profit when we use it together with the ability to do inductive reasoning that we share with all other animals. Most human cultures have difficulty programming computers and managing themselves in an effective way, because only a minority of people actually do inductive thinking. In most human cultures, most people only do deductive thinking (although everyone has the ability to do inductive thinking latent in them), with only a minority of people including poets, effective computer programmers and scientists, and real magicians doing inductive thinking. The work of this minority is what provides the new stuff that everyone else works through with their strictly deductive kind of consciousness.

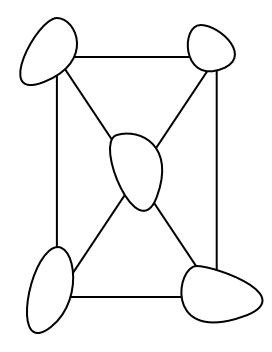

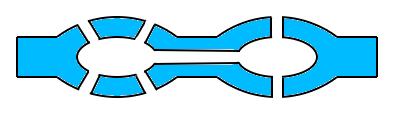

Let's look at an example where the kind of hidden rules that can't be found by deductive reasoning can make all the difference. Imagine we have a city built on five islands connected by bridges like this:

The question is, can the people of the city take a stroll which crosses all the bridges (for maximum variety), but doesn't cross any of them more than once (since that would be boring)? One way to find out would be to use a pencil and several pieces of paper, and try lots of routes. After a while we'd probably come to the conclusion that it probably can't be done, but we wouldn't know for sure. We might make an exhaustive list of all possible walks, by starting on each island in turn and crossing each bridge in turn, then crossing each bridge we then have available in turn, and so on. By testing every possible route we could become more confident about our answer, but we still wouldn't know for sure. What if we'd somehow missed a route, or made a mistake when checking one? What's worse, if the city went and got itself another bridge, we'd have to go through the whole business all over again!

To get this puzzle under control, we need to step into the secret world of walks and bridges. The key to it is the Zen like simplicity of the fact that every walk has a beginning and an end. Take another look at the map of the five islands. The island in the middle has four bridges connected to it. The walk could take the people over the middle island twice (which would account for two bridges both times), or over the middle island once (which would account for two bridges) so long as it also started on the middle island (which would account for one bridge) and ended on the middle island (which would also account for one bridge). It doesn't matter which bridges are which, we just need to count bridges.

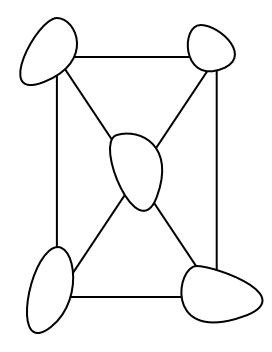

Now look at the other islands. They've all got three bridges connected to them. When we look at each island, we can account for two of the bridges by crossing over it, but the third bridge can only be accounted for by either starting or ending the walk on the island. If fact, because we can always account for an even number of bridges by crossing over the island, we can see that any island that has an odd number of bridges connected to it must be the start or the end of the walk. Since the walk can only have one start and one end, we can only do the walk if there are no more than two islands with an odd number of bridges connected to them. And the city has four islands with an odd number of bridges. That's four ends, so it must take at least two walks. We can be absolutely certain that we can't do the walk as the people want to do it! What's more, a moment's thought will tell us if the walk is possible when the city development programme adds more bridges. Look at this proposal for a new bridge:

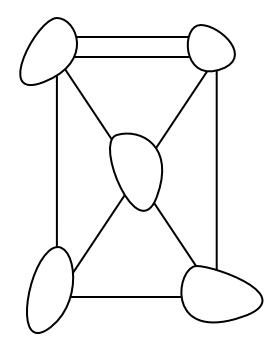

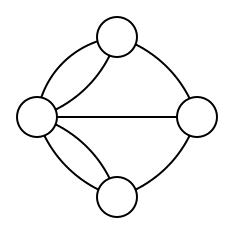

As soon as we look at this new plan, we can see that we have only two islands that have an odd number of bridges connected to them, so the morning walk is possible and what's more we can see that it must start and end on the two islands shown at the bottom of the map. It's ridiculously easy! Now look at this proposal:

Equally quickly we see that now there are four islands with an odd number of bridges connected to them, so the walk is not possible.

This little story is a true one. The city was Koenigsberg and the people of the Koenigsberg got so worked up about the puzzle of the walk that lots of them took to spending their Sundays walking round and round, trying to find the route that would let them cross all the bridges, once and only once. Eventually the problem was solved by Leonard Euler, one of the greatest mathematicians in history. The physical layout of Koenigsberg at the time looked like this:

All we need to do the apply Euler's insight is to squeeze the two stretches of land at the top and bottom of the picture together, and draw the bridges as we've been drawing them up until now. How many islands are there with an odd number of bridges connected to them?

It's the proceduralised kind of thinking - applying Euler's insight - which our culture can cope with, and it's the creative kind of thinking - which Euler did to solve the problem - which most cultures don't recognise, understand or use.

Can this really be true? Can it really be that in most cultures, most people don't use the most powerful part of their minds at all? It seems like a bizarre idea, because we live in a culture which only acknowledges the part of consciousness that everyone uses. Because of this, there is very little in people's day to day lives that points out to them that they are missing something. Even so, once we have the idea that something odd is going on, it's easy to find plenty of evidence that the whole culture really is oblivious to the most important stuff. We can only learn to see around the limited prejudices and assumptions that we have picked up from the culture around us since childhood if we understand the limitations.

Language offers a huge clue. We've seen how Native American languages have evolved to enable their speakers to discuss the complex of relationships that are visible to inductive thinkers, are process and action based and put their emphasis on verbs, while most languages have evolved for use by people who operate by sorting kickable objects into categories, are static and object based and put their emphasis on nouns. Even within English, we find that mathematicians are aware of the two kinds of thinking, and use the words "deductive" and "inductive". This awareness is in a rather specialised corner of the language though, and doesn't usually penetrate to people's day to day language. When mathematicians use the word "deductive", they are usually talking about problems that computers can do really easily, of the kind:

A man goes to the shop with £10. He spends £7.50 on shopping, and puts £1.00 in a charity box. How much does he leave the shop with?

On the other hand, when they use the word "inductive", they are talking about problems that computers can't do easily, and can't do with certainty at all, of the kind:

What is the missing number in this sequence?

2, 4, 6, ?, 10

The word "deductive" is not normally applied to people who work in call centres, having completely scripted conversations on the phone all day, but as they follow the little arrows on the scripts they are engaging in the kind of operation that a computer can do really easily. The word "inductive" is not normally applied to people who see that they can use modern computers and switchboards to sell motor insurance directly to the public, reducing costs to their customers and also make a profit, but as they do this kind of noticing they are doing something that a computer cannot do. In their specialised field, mathematicians know that there are two distinct kinds of thinking, but this awareness is not common in society at large. In most situations, deductive thinking is just called "thinking", and inductive thinking is called "intuition" (when it is called anything at all). Intuition is supposed to be a vague thing, that many people don't even believe exists at all, and certainly isn't recognised as central to getting anything useful done at all. In English, there isn't any word for deliberately setting out to find an insight, even though no competent manager, poet or programmer can do their work without performing this crucial stage! It's because of this that many people think that mathematicians and scientists spend their lives grinding out deductive thinking, with lots of "therefores" in it, and live sterile and boring lives. At the same time, many people think that artists operate in a completely disorganised way, with no discipline or skill at all to what they do, and reject regimentation because they are "rebels". We often see value judgements that describe people who live in a robotic, reactive way, repeating the same behaviours over and over again as having "good" habits, while people who simply do not do this are "rebels" or "non-conformists", irrespective of whatever it is they do in a non-robotic way. It's not what people actually do that makes them "good" or "rebels" in most cultures - it's simply whether they do it in a robotic, deductively based kind of a way or not.

We see the emphasis on deductivism in the legal systems which most cultures are based around. Even though we know that systems of rules cannot cover all cases, and certainly cannot enable us to manage businesses responsibly, all legal systems are constructed and operated as if responsibility consisted of nothing except applying rules to data written on pieces of paper. Legal systems are constructed as if people are limited to pushing pieces of paper around like computers push numbers around on hard disks. Whenever reactive bureaucrats preside over some terrible fiasco or other and there is a scandal, the response of their bosses is always to say that they are "reviewing their procedures". They seem incapable of appreciating that the problems caused by replacing individual awareness and responsibility with rules cannot be solved by replacing even more awareness with rules.

When groups of people get locked into deductive fixation, they tend to fall deeper and deeper into the trap. In extreme cases, the deductive ritualism takes on the properties of a fundamentalist religion. When the results of deductive, rule based behaviours are so ridiculous no-one could possibly claim they are desirable, the people involved often disclaim responsibility by arguing that since they have behaved robotically, the results (whatever they may be) must, by definition, be correct. We even hear people in positions of administrative authority arguing that their decisions - no matter how ridiculous - must be correct, since their decision making procedure is "perfect"! It is unlikely that any rulebook written by fallible humans could ever be perfect, even if the universe could be fully understood by systems of rules - and we know it can't. This strange attitude lies at the root of the saying, "the law is an ass". People seem to believe that we must accept the bizarre errors of purely deductive, rule based systems, because only purely deductive, rule based system are always assured to be correct! Since the results are clearly not correct, it must be the deductive behaviour itself which people have a deep-seated belief is inherently correct, and never mind the consequences!

This kind of attitude towards the errors thrown up by deductive, rule based behaviours is suspiciously like the idea of a "sacred mystery" - people defer to robotic administrative procedures as fundamentalists defer to robotic religious procedures. Fundamentalist effects can be seen in offices as well as in religions! When this occurs, people start to adopt a peculiar manner. They become complacent and arrogant at the same time as they become less aware of what they are not considering, and their mismanagement becomes worse. As things spiral into chaos, the trapped people become less aware of the problems. This reducing awareness, or specific kind of blindness, is particularly hard to argue against, because of the deductivist bias in the language and customs of the whole culture.

So when we look for it, we realise that everyone has seen - and is always seeing - plenty of examples where the deductive fixation throughout our culture leads to problems. Perhaps we should look at the question from the other side for a while. Perhaps the problems don't matter. There are several common reasons that people give for saying we should not think about these problems. Firstly, perhaps it doesn't matter because all that we are seeing is fecklessness, cynicism, stupidity and sloth. That doesn't actually tell us anything though. All that we do when we label and dismiss this kind of bizarre and self-damaging behaviour is to fall into the trap of performing a deductivist sorting behaviour and thinking we have understood. In Richard Feynman's father's language, we have named Spencer's Warbler but we still know nothing about the bird.

The second common reason for avoiding thinking about the problem of robotic behaviour is that it's just "the human condition". That's just another route into the labelling and dismissing trap though, because it doesn't explain why it happens. It's like saying that there is nothing to explain because it always happens, when in fact something like this needs understanding even more when it is so common. It's also a circular argument, because people who are happy to look at what is going on without preconceptions, and don't feel the need to always be following rules in what they do, don't get into the problems caused by purely rule based thinking. Being caught in rule based thinking is not a part of the human condition, just part of the condition of some humans.

Thirdly, perhaps we shouldn't worry about it because modern humans get on very well just behaving deductively, and there are always a few primitive inductivists around to take care of that kind of work. This reason for not thinking about the problems doesn't work though, because these days the machines are very good at doing everything that can be done by following rules. Human beings just can't compete. So if they can't use inductive thinking together with deductive thinking to program the machines, discover new science and technology, or create new artworks, what are they going to do with their lives? The idea that we should revert to a more primitive and materially poorer state because some people have an aversion to using all of their minds, and need to spend their time pretending to be robots would just be silly. It would be much better to find out why the people have the aversion to using all of their minds, and correct the problem. So it looks like the common excuses for not thinking about why many people are trapped in deductive thinking are themselves part of the trap!

The philosophers of our culture should be relieved to discover that the common explanations for the problems of deductivism don't work, and that the whole culture has a problem in this area, because they've never been able to get their heads round it either. To demonstrate this we can look at two examples, in the work of a philosopher of science called Karl Popper, and a mathematician called Kurt Godel. Popper was very worried about The Problem of Induction, and wrote an essay which didn't sort it out. From our point of view, even the title is interesting - he saw the problem as being the necessity of induction instead of the cultural fixation with deduction. (To be fair, Popper's thought is far richer and subtler than a simple fixation on deductivism, but in the case of his famous essay he was attempting to compare what reality does with his culture's assumptions about it - and he did the job superbly.)

What worried Popper was that science always proceeds by guessing, not just grinding out results in a purely deductive way. He wanted to find some way out of what his culture sees as a terrible situation where rules are not enough. In the end he came up with a very valuable idea for improving how we do science, but he wasn't able to get rid of induction. His idea was that new theories can never really be proven with the simple certainty we can get when we just add numbers together deductively. Induction is always a kind of guessing, and guessing can be wrong. So Popper said the most useful new theories are the ones which we can disprove if they are wrong, rather than the ones we can try to prove if they are right. It's a slippery idea, so let's have an example. A theory that London is infested by a race of giant hamsters is not very useful because every time we look, we might just be unlucky, and not find the hamsters even if they are there. We can't prove the theory is right by looking for giant hamsters in London. If the theory also said that the hamsters leave huge piles of hamster dung it suddenly becomes much more useful, because if we don't find the dung heaps we can prove the theory is false. Proving true is impossible, proving false is possible. That's a really useful idea to have, because induction is unavoidable. What's interesting about this work is why Popper's culture gets so upset about the need for uncertain induction in the first place. Since no animal in the universe has ever been able to be absolutely certain about anything, and Popper was equipped by evolution with a mind that could cope with the reality of a universe where induction is needed, why did he feel (on behalf of his fellow humans) that the universe was a hostile place to his kind of mind, and things would be better if everything could be done deductively? Here we can see that the problem is a cultural bias that values deductivism and does not appreciate inductivism.

An even more extreme example was other mathematicians' response to the work of Kurt Godel. Godel had a long and productive career, but he did one piece of work that was so significant that it is just called "Godel's Theorem". In this he proved mathematically that however we go about doing mathematics, there will always be some truths that can be proved true by deductive thinking once we have discovered them, but which we can never discover just by using deductive thinking. Since this is exactly the situation we've been discussing, it should be no surprise at all (although it's interesting that this situation has indeed been proven to be true at a fundamental mathematical level). We need both kinds of thinking to fully understand the universe and cannot use either kind to substitute for the other kind. (To be fair, there's another possibility in Godel's result - that the universe is nuts - but in that case deductive thinking goes out the window so we'll not worry about it here.) Inductive thinking discovers new stuff, and deductive thinking tests and helps to apply the discoveries. That's just the way our natural habitat (the universe) works, and anyone who is confident and experienced in using the faculties they were born with should think of Godel's theorem as old news. We have both kinds of thinking available, so everything is hunky dory. Yet at the time (and still today, 70 years after Godel discovered his theorem) most people who learn of it react with surprise. For some reason, they feel that they "should" be living in a universe where deductive thinking is sufficient on its own. The universe they interact with every day didn't give them this odd idea - it's a blind spot that comes from a whole culture of people who have been fixated on the deductive and avoiding the inductive long enough to evolve language and cultural norms that just don't work in the universe as it really is.

George Gurdjieff was a magician who was active in the early 20th century, whose ideas are mainly available in three books with the overall title All and Everything, and one book by his pupil P. D. Ouspensky called In Search of the Miraculous. In Ouspensky's book, Gurdjieff makes a very direct statement about the way people get trapped in deductive thinking, but are unaware that they are missing any understanding, and tend to create simplistic fictions to convince themselves that their understanding is complete:

In all there are four states of consciousness possible for man... but ordinary man... lives in the two lowest states of consciousness only. The two higher states of consciousness are inaccessible to him, and although he may have flashes of these states, he is unable to understand them, and he judges them from the point of view of those states in which it is usual for him to be.

The two usual, that is, the lowest, states of consciousness are first, sleep, in other words a passive state in which man spends a third and very often a half of his life. And second, the state in which men spend the other part of their lives, in which they walk the streets, write books, talk on lofty subjects, take part in politics, kill one another, which they regard as active and call `clear consciousness' or `the waking state of consciousness'. The term clear consciousness' or `the waking state of consciousness' seems to have been given in jest, especially when you realise what clear consciousness ought in reality to be and what the state in which man lives and acts really is.

The third state of consciousness is self-remembering or self-consciousness or consciousness of one's being. It is usual to consider that we have this state of consciousness or that we can have it if we want it. Our science and philosophy have overlooked the fact that we do not possess this state of consciousness and that we cannot create it in ourselves by desire or decision alone.

The fourth state of consciousness is called the objective state of consciousness. In this state a man can see things as they are. Flashes of this state of consciousness also occur in man. In the religions of all nations there are indications of the possibility of a state of consciousness of this kind which is called `enlightenment' and various other names but which cannot be described in words. But the only right way to objective consciousness is through the development of self-consciousness. If an ordinary man is artificially brought into a state of objective consciousness and afterwards brought back to his usual state he will remember nothing and he will think that for a time he had lost consciousness. But in the state of self-consciousness a man can have flashes of objective consciousness and remember them.

The fourth state of consciousness in man means an altogether different state of being; it is the result of long and difficult work on oneself.

But the third state of consciousness constitutes the natural right of man as he is, and if man does not possess it, it is only because of the wrong conditions of his life. It can be said without any exaggeration that at the present time the third state of consciousness occurs in man only in the form of very rare flashes and that it can be made more or less permanent in him only by means of special training.

Everyone knows what Gurdjieff's first or sleep state is! The difference between his robotic second state, where people are not fully conscious but think they are, and his third state where they are conscious of their own being (and can spontaneously notice what they and the things around them are doing without being told to) is the difference between being deductively trapped and the full human faculties. His fourth state is a more complicated question, but we already have a basis for it in the idea that in the fractal universe consciousness is not produced by the nervous system, but instead arises in the nervous system as it allows data already present in the universe to interact with itself. We'll look at this in more detail in Chapter 4.

This distinction between Gurdjieff's second, third and fourth states is found in plenty of other traditions. In Yoga, Buddhism and the Vedic traditions, there is the idea of the "chattering mind", or "false ego", which drowns out true perceptions with its unending, robotic dissections of the past and fantasies about the future. By moving their attention out of the present moment, and filling their minds with sterile and circular variations on the same closed and limited themes, the chattering mind prevents people having true consciousness of what is really going on in their lives. In these traditions, meditation is used to calm the chattering mind and allow true awareness to deepen and mature. Sufficient development leads to a different state of consciousness again, called "Buddha consciousness" or "turiya" (which just means "fourth").

In Gurdjieff's description of the situation, the third state, the "natural right of man" (all animals can think inductively), requires "special training" because of the "wrong conditions" of people's lives. That is, there is some environmental factor which prevents people enjoying their natural state of awareness. This is a theme that he also discusses in the first volume of All and Everything, called Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson. There, he describes the deductively fixated and robotic state in great detail, and claims that it is caused a part of human anatomy called the "organ kundabuffer". There is a lot of complicated stuff about whether or not the organ kundabuffer still physically exists in modern humans, and whether or not it's effects are now natural and appropriate to humans, but Gurdjieff is certainly clear that most humans are limited in their perceptions, and that this is caused by some physical part of their anatomy. Yet in other parts of the same book, he claims that people's limited perceptions are caused purely by the "un-natural conditions of their existence", exactly as he told Ouspensky. In still another part of the same book, he claims that the unaware and robotic state is something that has been "put into man".

Is the robotic state natural or not? Is it produced by human anatomy, or by external conditions? As often happens when trying to make sense of the magicians, we have to realise that the answer is "all of the above"! Perhaps we can avoid the superficial contradictions if there is something natural and beneficial going on, which has somehow been distorted into a unhealthy state by external conditions. We already know about examples of this kind of thing going on. Just to get used to thinking about things in this way, we can start with an example found in intensive, battery pig farms (and was a major cause of this approach to farming becoming less popular in recent years).

During the 1970s, scientists discovered an important group of chemicals called the endorphins. Endorphins are nature's painkillers. When any animal is injured, pain at the site of the wound prevents the animal from moving its damaged part, to allow healing to take place. Usually, the pain benefits the animal, by preventing it doing further harm to itself. In the first moments after the injury is sustained though, pain is not helpful to the animal. It is usually much better for the animal to be able to move away from the situation where it was hurt, and find a safe place to recover, even if moving would make the wound worse. So for a while after all animals have suffered an injury, they produce endorphins, which numb the pain of the wound, and allow the animal to continue to move. The animal only becomes aware of the pain after the endorphins have worn off. After the endorphins had been discovered, scientists quickly realised that drugs including morphine and heroin work because they are chemically very similar to endorphins. When a doctor injects morphine into an accident victim, she is artificially turning on nature's own pain control mechanism, to make the patient more comfortable where nature's course is to keep the patient pinned down with pain. So long as the patient remembers to lie still, she can be safe and comfortable too.

Soon after the endorphins were discovered and their job was understood, scientists found them in the blood of battery farmed pigs that had been observed behaving in very odd ways, making pacing motions, over and over again, in their tiny stalls. They soon realised what was happening. Battery farmed pigs had a very unhappy life. They suffered, but the suffering was long term and emotional, and did not trigger the release of endorphins. The pacing behaviours were also very boring and stressful for the pigs, but the suffering caused by the pacing was more acute and physical, and did trigger the release of endorphins. So the miserable pigs had discovered that by pacing, they could numb themselves to the misery of their existence. They had become pig junkies, who had found a way to make their own misery numbing drugs. These discoveries shocked many people who learned about them, because apart from anything else they proved that battery farmed pigs really did suffer as a result of their conditions. The chemistry spoke in a way that the pigs could not, and all claims that they were dumb animals who did not suffer because of battery farming methods were proved false.

We can compare the pigs' pacing with Gurdjieff's statements. Is an alert and aware state the "natural right of pigs"? Yes - if the pigs live in conditions that are natural for them, they don't perform behaviours that cause them to secrete endorphins, and don't exist in a numb state. Is their numbed state caused by their anatomy? Yes - the endorphin system is part of their biology. Is the numbed state caused by their "wrong conditions"? Yes - if they weren't in battery stalls they wouldn't be miserable and they wouldn't pace. Has the numbed state been "put into pigs"? Yes - in the same moment the pigs were put into the stalls.

For another example of this kind of thing going on, this time in humans, we can look at the problem of adrenaline addiction. Adrenaline is a perfectly healthy hormone, that we have evolved to release for short periods when we need to call on our full reserves of strength - such as when attacked by lions. In recent years, some people have been engaging in lots of very exciting sports, which give them a buzz and cause them to release adrenaline. The trouble is, there can be too much of a good thing. When people spend too much time releasing adrenaline their bodies can find a new chemical balance that includes the elevated levels of adrenaline - they develop a tolerance. If they then stop doing the exciting sports, they experience the other side of tolerance - withdrawal. In this way, people can become addicted to their own adrenaline, and are driven to do more and more dangerous things to keep getting their fix. This can distort people's judgement, so that they do things that they would have thought of as quite insane before becoming addicted to adrenaline. Perhaps this explains the growth in the strange sport of BASE jumping. BASE stands for Buildings, Antennae, Spans and Earth features - the classes of things that BASE jumpers like to parachute off and often get killed as a result.

Just like the pigs, the adrenaline addicts' problem is caused by their own anatomy, by their wrong conditions, and has been put into them by their choice to spend too long in the wrong conditions. Gurdjieff was describing something similar happening in human beings. The only difference is that instead of numbing misery or improving strength and reflexes, the mechanism that is being over-used in humans turns off the most important part of their minds.

Why would any animal benefit from having an off switch for its mind? At first it seems like something most creatures would want like a hole in their heads! Humans are different to most creatures in two ways though, and taken together these differences make an off switch for the human mind a very useful thing indeed.

For one thing, humans don't have physical defences against other animals who might want to eat us. If a lion, a wild boar or other animal attacks us, we'll probably lose the fight. If we try to outrun the lion or boar, we'll quickly find ourselves back with the fight problem. We don't even play the numbers game like herds of gazelle or shoals of fish do. If a lion spots us, there's a good chance that we ourselves, and not one of our friends, will end up tagged as lunch. We don't have the usual kind of defences because we don't need them, and that's our other oddity. We are also smarter than any other creature on earth. If we are prepared (the deductive mind helps with that) and can imagine different possible futures (the deductive mind helps with that too), we can be clever when we are attacked. We can climb a tree, or duck into a cave or crack in the rocks, and use our spear or even a makeshift piece of branch to repel the attacker. Because the attacker is always going to be faster and stronger, getting into siege situations like this must have been a common problem for our distant ancestors. We are descended from a long line of people who spent a lot of their time hiding in caves or up trees, waiting for other animals who wanted to eat them to go away.

The trouble was, as soon as our ancestors had completed their brilliant plan and got themselves to safety, those wonderful brains turned against them. Picture it. You're in the cave, waiting for the lion to go away. The lion is outside the cave, waiting for you to come out. Whoever gets bored first is the loser. And the lion with his puny brain has the birds and the antelopes to look at. You with your pinnacle of evolution brain have a wood louse to squint at in the darkness of the cave - if you're lucky. Who's going to get bored first? Is the lion going to wander off and look for something else to pick on, or are you going to decide to make a break for it?

Of course you're going to lose. You're much more easily bored, and much less stimulated than the lion. You're going to make a break for it, and you're going to be lunch. You aren't going to get back to the tribe, and you aren't going to be producing any more offspring. Unless, of course, you're an odd kind of an early human that somehow responds to low level stimulation by getting stupider. Not completely asleep, you understand. Otherwise you won't be able to prod at the lion with your bit of stick every time it tries to get it's paw into the cave, and you won't be able to notice when it finally gives up in disgust and goes away either. A nice, comfortable, happy kind of a feeling would be good too - so you really don't feel any need to move until the lion's gone and you realise it must be teatime soon. If you were an odd kind of an early human like that, you could outwait any creature, no matter how stupid it was, that didn't have it's own off switch for its mind. The rest of the story is pretty obvious. You make it back to the tribe, and given the high casualty rate, you collaborate in the production of lots of offspring.

So it turns out that if evolution can find a way to do it, providing human beings - and quite specifically human beings - with an off switch for their minds, would be a very useful thing to do. Then the existence of the off switch would make humans vulnerable to a particular kind of trap. If people got their minds stuck in the off position, they would suffer from distorted perception just like the adrenaline addicts. They'd get used to boring themselves to keep their minds turned off, instead of just having their minds turned off by nature when conditions happened to be very boring. Like an adrenaline addict, they'd start to think of themselves as doing things that obviously made sense, and those around them who see things in a very different way, and were not driven to bore themselves to maintain their addiction as wrong. They would not be able to distinguish between value judgements distorted by the addictive state and stuff that really made sense.

Apart from a few lucky ones who meet inspiring teachers in their younger years, most people who retain their ability to think inductively tell horror stories about their school years. For these people, school is usually just a few years of misery that they endure before being able to get on with life and achieve success in their own terms. In recent years has it become fashionable in some schools to characterise these people as mentally handicapped, with an affliction called Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is sometimes just called Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD).

To show that we really are talking about people who have access to their full faculties and are able to cope with the universe as it really is, we can look at a short piece written by a person who has often been told that he suffers from this terrible affliction, but who has retained his self esteem, and enjoys being himself. This piece by Bob Seay is taken from Additude Magazine, visible on the Internet at www.additudemag.com, and describes the ways he knows he is unusual:

Considering what we have already looked at, this piece is simply a description of a healthy human being. Seay lists the ability to use intuition and analogies to make sense of the structure he perceives in the universe, and appreciate the big picture. He can be creative, and is good at abstract and theoretical stuff as well as enjoying the energy and drive that comes from being passionate about his interests. Because he can see and make sense of the big picture, he feels confident to try new things, can improvise, and has a framework which allows him to learn new things very quickly. The same big picture makes him compassionate, fair minded and generous. This isn't a matter of being sanctimonious, it's just a natural consequence of having a wider perspective. And he notes that creative artists, great thinkers and successful entrepreneurs share this character type with him.

So why on earth have people trapped in deductive thinking got it into their heads that this healthy, lively, useful and powerfully able person is mentally handicapped? The problem is that when people get trapped, they lose the faculties Seay describes, and their priorities become distorted towards robotic behaviours. They do not recognise or value Seay's faculties, and see his disinterest in behaviours they think are very important as an inability to perform them. The addictive trap is at its most powerful in large, highly proceduralised organisations, and we can see the incomprehension in this piece, quoted from the American National Institute of Mental Health, at www.himh.nih.gov:

At present, ADHD is a diagnosis applied to children and adults who consistently display certain characteristic behaviors over a period of time. The most common behaviors fall into three categories: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

Inattention. People who are inattentive have a hard time keeping their mind on any one thing and may get bored with a task after only a few minutes. They may give effortless, automatic attention to activities and things they enjoy. But focusing deliberate, conscious attention to organizing and completing a task or learning something new is difficult.

For example, Lisa found it agonizing to do homework. Often, she forgot to plan ahead by writing down the assignment or bringing home the right books. And when trying to work, every few minutes she found her mind drifting to something else. As a result, she rarely finished and her work was full of errors.

Hyperactivity. People who are hyperactive always seem to be in motion. They can't sit still. Like Mark, they may dash around or talk incessantly. Sitting still through a lesson can be an impossible task. Hyperactive children squirm in their seat or roam around the room. Or they might wiggle their feet, touch everything, or noisily tap their pencil. Hyperactive teens and adults may feel intensely restless. They may be fidgety or, like Henry, they may try to do several things at once, bouncing around from one activity to the next.

Impulsivity. People who are overly impulsive seem unable to curb their immediate reactions or think before they act. As a result, like Lisa, they may blurt out inappropriate comments. Or like Mark, they may run into the street without looking. Their impulsivity may make it hard for them to wait for things they want or to take their turn in games. They may grab a toy from another child or hit when they're upset.

Not everyone who is overly hyperactive, inattentive, or impulsive has an attention disorder. Since most people sometimes blurt out things they didn't mean to say, bounce from one task to another, or become disorganized and forgetful, how can specialists tell if the problem is ADHD?

To assess whether a person has ADHD, specialists consider several critical questions: Are these behaviors excessive, long-term, and pervasive? That is, do they occur more often than in other people the same age? Are they a continuous problem, not just a response to a temporary situation? Do the behaviors occur in several settings or only in one specific place like the playground or the office? The person's pattern of behavior is compared against a set of criteria and characteristics of the disorder. These criteria appear in a diagnostic reference book called the DSM (short for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

According to the diagnostic manual, there are three patterns of behavior that indicate ADHD. People with ADHD may show several signs of being consistently inattentive. They may have a pattern of being hyperactive and impulsive. Or they may show all three types of behavior.

According to the DSM, signs of inattention include:

- becoming easily distracted by irrelevant sights and sounds

- failing to pay attention to details and making careless mistakes

- rarely following instructions carefully and completely

- losing or forgetting things like toys, or pencils, books, and tools needed for a task

Some signs of hyperactivity and impulsivity are:

- feeling restless, often fidgeting with hands or feet, or squirming

- running, climbing, or leaving a seat, in situations where sitting or quiet behavior is expected

- blurting out answers before hearing the whole question

- having difficulty waiting in line or for a turn

Because everyone shows some of these behaviors at times, the DSM contains very specific guidelines for determining when they indicate ADHD. The behaviors must appear early in life, before age 7, and continue for at least 6 months. In children, they must be more frequent or severe than in others the same age. Above all, the behaviors must create a real handicap in at least two areas of a person's life, such as school, home, work, or social settings. So someone whose work or friendships are not impaired by these behaviors would not be diagnosed with ADHD. Nor would a child who seems overly active at school but functions well elsewhere.

There are a great many misconceptions in here. Seay does not have any problem keeping his mind on any one thing, as he himself states. The difference is that he keeps his mind very focused on things that interest him, and he gets bored by boring things. (Deductivists explain this ability of healthy people to focus much more than they can by nouning it as "hyperfocus", and then saying that hyperfocus is a symptom of inattentiveness!) Healthy humans focus on things that interest them with great drive and enthusiasm. People trapped in robotic behaviour will plod on at anything they are told to with exactly the same disinterested lack of enthusiasm in every case. Describing the intense concentration that is required to do creative work as "effortless and automatic" also seems very odd until we realise that people trapped in robotic behaviour never have experience of doing creative work. Since this part of their own minds is asleep, they assume that this kind of work is not done by the mind! In the same way, people who can't see structure can only learn by slowly and painfully rote memorising unconnected facts. They don't perceive a big picture that all the little facts just fit into. So they sit in lectures frantically taking notes, they revise, they cram. People who see the big picture don't need to do any of this stuff, but the robotic people are so convinced that the painful and shallow way is the only way to learn that they carry on claiming healthy people are incapable of learning even after they turn in straight A exam results!

There are also a lot of problems concerned with social behaviour. Robotic people think of social relationships as being about going through the motions of scripted exchanges and so "fitting in". What they're actually doing is boring each other, and doing this seems obviously right because everyone involved is maintaining their boredom addiction. Healthy people think that conversations are about exchanging data about reality so that everyone can enjoy seeing new things. So they often draw attention to issues that the robotic people want to pretend don't exist! This is what is meant by "inappropriate" comments. In the same way, robotic people value the singsong exchanges between teacher and pupil more than the information content. Healthy people think that the purpose of asking questions is to obtain the answer. Note that there is no suggestion that the "inappropriate" comments are untrue, or that the "blurted" answers are incorrect. It's a matter of different objectives. One group is interested in what is happening in reality, and the other group is interested in boring, scripted social exchanges.

It's important to remember that from the point of view of healthy people, the most interesting parts of the world are simply missing from the robotic people's agenda. This leads them to feel a great sense of sterility, boredom and loneliness. They also feel that they are always being whined at over trivialities. For example, Thomas Edison didn't need to write "Invent the lightbulb" on a piece of paper to remember that he wanted to do this. His drive and determination to solve the problem led to him trying thousands of experiments before he found a suitable material for the filament. Healthy people only become involved with things that they feel passionate about in this way, because there's no time for anything else. Because robotic people don't ever have this experience of passion, their lives only contain matters that healthy people consider trivial. On one famous occasion Albert Einstein and a colleague were crossing a street in Princeton when his colleague made a chance comment. Einstein was so struck by the profound implications of the comment that he stopped walking in the middle of the street. Unfortunately modern teachers and health professionals would discount Einstein's visionary contributions to human knowledge, and explain that he was a mentally handicapped person who was incapable of remembering that he had to walk to the other side of the street.

Deductivist fixation traps its victims in a seemingly self-consistent picture where nothing is missing. The less aware a person becomes, the more they become convinced that their understanding is total and perfect. No matter how silly the things they say, they'll always find something sillier to confirm it. It's an attitude that can't be reasoned with from the outside, and in which people can do very dangerous and damaging things. If he was subjected to this kind of nonsense for enough years, Einstein might become very upset indeed. In the same way, many healthy young people are subjected to constant trivial nagging and insults, by people who (although they don't realise it themselves) are driven to dislike the healthy people because they don't participate in the mutual maintenance of boredom addiction. No matter how hard they try to reason with their detractors, the healthy people can never succeed. At the same time, the way that robotic people always feel the need to be rushing from one scripted series of physical actions to another prevents healthy people from getting the quiet quality time that is needed to assimilate and contemplate their experiences. So it's no wonder that many healthy young people are in a state of emotional distress at the present time.

The fashion amongst some people trapped in deductive thinking for describing healthy, creative children as mentally handicapped has caused a great deal of suffering. Yet as so often happens in this universe that is crammed full of patterns, a very valuable benefit has come along with the suffering. The error has led to lots of research being done to determine how so-called ADHD people differ from the majority, and this research has succeeded in finding a specific difference. So long as we remember that the difference doesn't cause a mental handicap at all, but instead provides immunity to sinking into the listless, robotic state that everyone else is vulnerable to, we have in this research a treasure that the magicians have been seeking for millenia.

The great discovery in brain chemistry that explains the human vulnerability to falling into an unhealthy spiral of diminishing awareness, robotic behaviour and deductive thinking was made by Professor Russell Barkley of the University of Massachussets. Because he is trapped in deductive thinking he sees his own work exactly the other way round, and believes he has found the difference that handicaps people so that they are unable to be robotic. To understand Barkley's contribution from the magicians' point of view, we have to separate his chemical discovery from the reasoning he has built on it, because his reasoning is focused on using the difference to explain a mental handicap that doesn't exist.

Barkley has discovered that people who are liable to be diagnosed as having ADHD (that is, people who are non-robotic and picked on by teachers) all have much lower levels of a brain chemical called dopamine than robotic people have. He has also discovered that non-robotic people have one of two genetic differences, compared to the majority of people. Non-robotic people with the first difference are able to remove excess dopamine from their brains much more quickly than most people. Non-robotic people with the second difference have a particular dopamine receptor that is the wrong shape, and doesn't bind to dopamine at all.

Like adrenaline, dopamine is an important chemical in our bodies. It's used to stop motor nerves firing after the brain stops telling them to move the muscle they are responsible for. Without dopamine, the brain fires a nerve to make a muscle move, and when the brain stops the nerve keeps firing for a while, so the muscle keeps moving even when the person doesn't want it to. In Parkinson's Disease, people lose the ability to make dopamine at all, with the result that their muscles don't stop moving when they should. It's when the person uses the opposing muscle to try to correct the extra movement, and that movement doesn't stop when it should either, that the person finds themselves with two muscles pulling against each other, and the shaking characteristic of Parkinson's starts to happen. So in most situations, dopamine is understood to be a neuro-inhibitor. It's presence stops nerve cells from firing, like pouring water on a fire.

There are lots of situations in our bodies where one part of our body (and that includes our brains and every other part of our nervous system) wants to signal to another part. In modern computers, signals like that are usually carried by electrical signals moving along wires. In our living bodies, signals are usually carried by chemicals that are released by the sender and detected by the receiver. There are many kinds of cells that have receptors on them, that are good for detecting different kinds of chemicals and so receiving chemical signals. Receptors work by having a shape that is just right for the chemical they detect to fit them, and chemically bind. When the receptor binds to the chemical it detects, the cell has detected the chemical. So that the signal can be sent again when it is needed, chemical signalling systems also need the ability to remove signal chemicals after they have been used, and make the system ready to detect the chemical again.

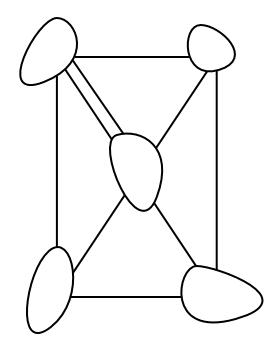

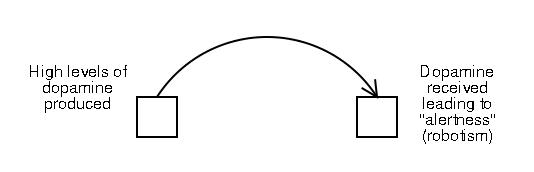

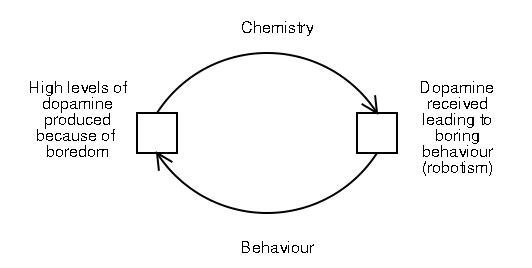

Because Barkley has discovered that robotic people have high dopamine and a particular group of dopamine receptors (called the DRD4 dopamine receptors) that correctly fit dopamine, he has concluded that in order to be robotic (which he thinks is healthy), people need to be constantly receiving a dopamine chemical message from themselves, like this:

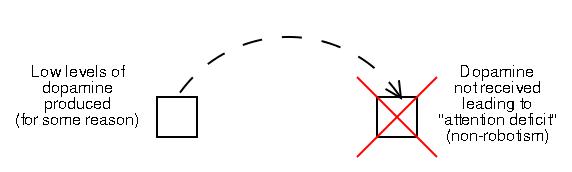

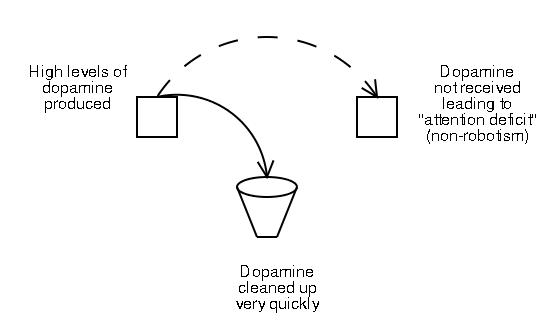

Some people are not able to receive the dopamine message from themselves, because their DRD4 receptors can't bind dopamine. Because of this, Barkley thinks they are not able to be robotic, and this makes them mentally handicapped. He has also noticed that they have low levels of dopamine in their brains, although they don't seem to have any problems producing dopamine. Barkley doesn't say why he thinks the inability to receive dopamine means the non-robotic people stop producing it. So Barkley sees non-robotic people doing this:

From the magicians' point of view, we can understand the DRD4 dopamine signal path as the physical mechanism of the off switch for the human mind. It's Gurdjieff's organ kundabuffer. Following the example of adrenaline addiction, where behaviour causes more message, and message causes more behaviour, we can draw the diagram for people trapped in robotic behaviour like this:

This full picture shows the reason why people with a non-working DRD4 receptor also produce low amounts of dopamine - it's because they aren't doing the boring behaviours that raise dopamine to try to turn their minds off. The same idea explains why people who clear up dopamine very quickly can stay free of boring behaviour. Even if they engage in boring behaviours, not much of the dopamine they produce gets through to turn their minds off:

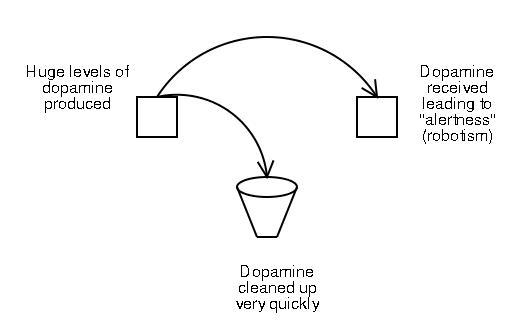

Such a person can only turn their minds off when they get so bored that they produce huge amounts of dopamine, and enough gets through to turn their minds off:

This way of understanding Barkley's discoveries explains a great deal, from the magicians' point of view. The hard core of people who can never turn off their minds because their DRD4 receptors don't work, comprise about 3% of the population. They are the ones who get into the most trouble with the robotic people around them, and have the greatest opportunity to start to see things in the way the magicians do, because their minds are always turned on. They are also the most vulnerable to feelings of loneliness and sterility in the world around them, and so more vulnerable to depression and emotional damage. Other studies, done by different people to Barkley, have identified exactly the same variation in the DRD4 dopamine receptor as an "alcoholism gene", because many people who end up in trouble with alcohol or other sense numbing drugs share it. In fact, the gene doesn't code for alcoholism any more than it codes for mental handicap. It codes for staying awake when everyone else goes to sleep with their eyes open, and when people don't realise what is happening, they can get very upset and turn to alcohol. Perhaps it is not surprising that the DRD4 variation is often found in Celtic peoples, bearing in mind their excellent traditions of poetry, music, and curious non-deductive modes of thought. Still other studies claim that exactly the same DRD4 variation is a "novelty seeking" gene, which causes people to be very energetic and seek new experiences. Of course they are indeed novelty seeking in comparison with their boredom addicted neighbours, but that's a relative judgement. They don't have a gene that makes them seek novelty, instead they have a gene that stops them avoiding it, so they retain the human normal level of interest in novelty! The way that three groups of deductively minded scientists, working in exactly the same area, can describe a single gene as coding for mental handicap, dynamic successfulness and alcoholism, without realising the contradictions in what they are saying, is itself a striking example of how far from sense reactive deductivism acting alone can stray. When the inductive ability to spontaneously notice something, pause and say "Hold on a minute..." is lost, nonsense and contradictions can build without end.

The second group of people with genetic immunity to falling asleep don't enjoy the kind of protection that people with the DRD4 variation have. This group comprise about 17% of the population. If things get boring enough they will become robotic, but it takes much more boredom to do this than most people need. These are the people that seem to go through life changing their values and approach over and over again. During periods of full awareness they develop interests and relationships that fulfil them. Then after a period of under-stimulation they sink into robotism, and the activities that they previously found fulfilling seem to them to be ridiculous and lacking because they don't give provide them with enough boredom to maintain their addiction. From the outside, their awake friends see them as becoming shallow and like a herd animal. After a while they go through a period of change, perhaps occasioned by a change in their job situation, and they snap out of it. Then they find their activities boring, and their current crop of relationships tedious and scripted. Because they always spend some of their time in a herdlike state of mind, these people learn the behaviours that only members of a herd can notice, so they don't suffer as much unpleasantness from the majority who are permanently trapped in robotism, but they also go through life not understanding that it is they who are changing rather than authentically interesting lifestyles always proving wanting, and their own personal development is interrupted by periods of robotism so often that they rarely make much progress in the poetic direction, even though they often yearn for this.

When we add the 3% of full immunes to the 17% of partial immunes, we have 20% of the population - one person in five - who have some experience of doing inductive thinking, and the richer universe which it reveals, at some time in their lives. This exactly matches the observation of the founding psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who was very interested in the deeper nature of human perception, and said that one person in five would have what he called some sort of "spiritual" perception during their lives. Here we see that we don't need to imagine some spooky other dimensions or hidden connections for spiritual perception to happen. Everything that is real happens in front of our noses, here in this universe, and seeing what is there is as natural as breathing. It's just that most people have their natural faculties for seeing what is there asleep, leading to lurid tales of bizarre visions of other dimensions and so forth.

How might the chemical off switch for the human mind operate? In the last chapter we saw that the magicians' idea of consciousness is a universal effect which individual creatures experience from one point of view. We saw that there is a physical, non-spooky way of understanding this if our nervous systems reflect incoming fractal data, which can then make sense of other incoming data because all incoming data, at all levels of abstraction and in all contexts, is part of a single fractal pattern. For this to work, our nervous systems must hold incoming data, and feed it back to mix it with other incoming data. Our memories must consist of much more than lists of rote memorised facts, and must contain remnants of every sensory experience we have ever had, echoing round and round, ready to be mixed in with new data entering our bodies, just as experiments involving direct electrical stimulation of the brain or hypnotic regression indicate. People who have their memories stimulated in this way can indeed remember every sensory detail of experiences that they had many years previously. So all the data needed for a feedback process where incoming data is mixed in with prior input is indeed available. This kind of feedback is sometimes used in engineering, and very often by electric guitarists. As anyone who uses feedback knows (and this includes guitarists), the amount of amplification of the signal must be exactly right. Too little amplification and the signal quickly dies away to nothing. Too much and the signal quickly becomes an unmanageable howl. For the human nervous system to exploit feedback when it detects the patterns in the data entering it, its level of excitability must be exactly right. We know that dopamine is a neuro-inhibitor which is used by all animals to stop motor nerves firing when the animal wants to stop moving its muscles. So dopamine was available to evolution when our species faced the problem of out-waiting less intelligent animals in siege situations. Learning to raise the level of dopamine and make some cells in the brain that are sensitive to it would be a very easy way to squelch the feedback, and stop the brain being a useful medium for incoming fractal patterns to detect themselves. This fits with the experience of people who manage to break themselves free of the robotic trap. At first they have to make a lot of effort to break themselves out of their habitual rut, without any perceived change in their own consciousness. Then all of a sudden, their humour, awareness of their situation, awareness of their own bodies, their sensuality, energy and awareness of their own options all explode, and they experience a sudden change in their state of mind. This is not a linear effect. It's more like a switch turning on. If we understand this as their dopamine levels dropping to the point where the feedback loop is exactly adjusted, then we can understand why this deeper awareness turns on and off like a switch instead of being a gradual effect. On the other hand, when people get trapped in robotic behaviour, after they have lost their full awareness, they can be seen gradually sinking deeper and deeper into self-absorption, complacency and inability to notice even full scale emergencies in their immediate vicinity. If we understand this as the dopamine/behaviour cycle getting worse, we can see why once full consciousness has turned off like a switch, people can reach different levels of introspective boredom addiction, with people like junior bureaucratic clerical workers being chronically unaware, and shop workers who enjoy more stimulation being more aware of their immediate physical surroundings.

To finish up this look at the underlying chemistry of true awareness, we can compare the situation of people trapped in robotic behaviour with that of people trapped in cocaine addiction. We know that cocaine has its effect on the mind by stimulating dopamine production, and produces a state which looks very different from the outside (where the person seems to be quite unaware of the pressing issues in their lives) and from the inside (where the person feels completely confident and that they have complete mastery of the situation). Experiment usually confirms that such people have lost the plot, when the repossession crew takes away their belongings. From the magicians' point of view, the delusional state caused by massive dopamine production stimulated by cocaine is identical to the delusional state caused by massive dopamine production stimulated by very boring behaviours. Both are equally delusional and unhealthy. On the other hand, those who see robotism as inherently healthy have to jump through hoops to square this one. They have to acknowledge that the cocaine addict, talking complete rubbish between chopping up lines and having his possessions taken away has lost the plot, but they also have to claim that the chronically robotised clerical worker who has the same brain chemistry and talks equal rubbish as she fails to produce adequate customer service and her employer goes bust, is inherently healthy simply because she is robotised. The desirability of high dopamine levels and the effects they cause becomes a matter of social mores rather than the effects of chemistry. Such hoop jumping can often be seen in people who are led by boredom addiction to think they can always noun their way out of contradictions.

How did we get into the situation where most people are trapped in an addictive state, driven to maintain the level of boredom that keeps their minds turned off, so that they can't even become aware of what they are doing, or even recognise the problems caused by their abnormal mode of consciousness? How did most of the species get caught in a trap which converts a natural and useful ability to the stuff of nightmares?

There is a huge clue in the curious fact that history has a very sharp cutoff. The humans of today are no different genetically to the humans of 6,000 years ago, but we have no records at all of how humans before 6,000 years ago lived, what they knew, and what interested them. It's rather lame to say that they were primitive and so they lived like animals and left no records. If one of their children was brought up in our culture she could learn to operate a sports car, a Web browser, a microwave oven and everything else we use. She could breed with a modern human with no problem at all. 6,000 years is the blink of an eye in evolutionary terms, so the people of 6,000 years ago were every bit as smart as we are. Yet we, in our robotically trapped culture, know nothing of how humans lived before the invention of farming - and farming is a robotic activity. We know nothing of human history except the history of our own robotic culture, through thousands of years of farming and a few hundred years of technological development. From the inside, that seems like a whole lot of history. It's only when we wonder why we don't know anything about what happened before farming that we realise that we might just be missing perhaps 97% of human history.

With the idea of human vulnerability to boredom addiction available, and the example of the few humans today who do not live in robotised cultures, we can construct a rather chilling picture of the relationship between mass boredom addiction and farming. We start with the lifestyle of the remaining Native Americans. Recent studies have shown that hunter gatherers spend a smaller proportion of their time on assuring their basic living that any other cultural type on the planet, through all of history that we know about, except our own automated, mass production culture. So Native Americans have plenty of free time, which they spend in a world filled with entertaining patterns of natural richness. They possess a language that can be used to describe the world they see, as they see it. In cultures where all members have structural awareness, all members have excellent structural memory, so they don't feel the need to abdicate responsibility for memory to pieces of paper, carved rock or whatever. The legends that form the core of language itself are also the core of a rich oral tradition.

Imagine such a group of humans, using their full faculties to track natural ebbs and flows in their ecosystem and living comfortably. One day, they get an idea suited to the deductive part of their minds - instead of going to stand where the stuff they need will be arriving, they could form a team, divide up the tasks, and start making the stuff they need without waiting for it. At first it might just have been something as innocent as a production line for travelling bags. It probably seemed like a good idea at the time, because the thought of no-one having to make another travelling bag for another year or so must have been pretty entertaining. So they got into division of labour, with one person cutting up the hides, another making holes, another cutting thongs, another stringing them. It was boring but perhaps it was raining, or winter, and they didn't have anything better to do, so they kept at it.

They just kept at it for a bit too long. Quite a bit longer than they'd ever have been stuck in a cave waiting for a predator to go away. As soon as they got bored, their off switch cut in, and after a while they'd developed a tolerance for the raised dopamine level. When they stopped, they suffered withdrawal stress. They didn't like it, and they didn't realise what the problem was. How could they - their inductive faculty was asleep! When someone suggested doing some more production line stuff, it seemed like a very, very good idea indeed. And with their inductive faculty asleep, they didn't feel like they were missing anything from their inductive faculty being asleep. The addictive state must have spread like wildfire, as more and more tribe members were recruited to help co-fix boredom inducing behaviours. Pretty soon, a culture which was based on a libertarian ethic where anyone did exactly what they wanted so long as they didn't hurt anyone else, got turned around so that being compliant - co-fixing boredom inducing behaviours - was inherently virtuous, while not being compliant was inherently wrong. Proud independence was replaced by servile compliance. Reducing the amount of environmental stimulation of all kinds would have been universally seen as desirable, so a drab uniformity of dwelling places and even personal appearance would become valued.

Production line life was much less efficient than the old hunter gatherer way of living, but it still produced a surplus, because robotic fixation and lack of awareness meant that people never did anything except produce goods and children any more. With the self awareness provided by inductive thinking gone, traditional awareness of their own behaviour and the need to control population would have gone too. In the short term that wouldn't have mattered, because the surplus was there to feed all the kids. As children were born into the worsening situation, their freely expressed natural energy would have reduced the level of boredom in society. For people trapped in boredom addiction the correct solution would have been obvious. As soon as the children were old enough to be told what to do - say around four years old - they would have been given simple repetitive behaviours to perform until they learned to be compliant. By age six they would have become boredom addicted themselves, and stopped irritating their parents by always asking, "Why?". This natural and healthy behaviour of all humans would have been redefined as a "phase" that children go through. The first generation gap would have opened up, between those elders who'd never been tempted by the new approach to life, and their deductively trapped grandchildren.

Perhaps the grandparents tried to tell the kids what had happened. Perhaps, in their full featured, verb based language, they explained to the grandchildren that their parents had thrown away their traditional, understanding based approach to life, and replaced it with rote memorised simple tasks. They'd known it was unnatural because it was so boring, but they went ahead and did it anyway. They'd then taken to nagging each other to behave in this way, and covering themselves with those silly cloths to make themselves all share the same drab appearance. Things used to be wonderful round here - now it's all gone to pot. They'd completely lost their wits, so it was hardly surprising that the tribe was now over-run with grandchildren. That's just nature having its way when people's brains stop working.

The grandchildren wouldn't have heard that though. They were looking at life from a completely different perspective. Nature, freedom and exploration meant nothing to them. What mattered to them was following the procedure. They didn't have the necessary part of their minds awake to do understanding, and what could possibly be more wonderful than the feeling of total mastery that they got from rote memorising tasks and performing them? When the grandparents spoke, the kids would have heard something different. "One day humans discovered the secret wonder of rote based knowledge. The Great Sky Supervisor told humans not to try it, but they failed to follow the procedure and did so. The Great Sky Supervisor was angry because then the humans knew about compliance and non-compliance which was his big secret until then. They even realised that they weren't drab, and they'd been so stupid until then that they hadn't even realised that before. So the Great Sky Supervisor threw the humans out of the really nice place where they had lived until then, and told them that it is the procedure to have lots of children."

That's what happens to an oral tradition when the tribe loses its collective wits. Year Zero. They lost it all. Every time a group of free humans encountered a trapped one, the easy going free ones allowed themselves to be bullied by the trapped ones, and another group was caught. Trapped groups found that they could structure every exchange in their society, from preparing their food to propositioning potential sexual partners, in a ritualised way. This bizarre ritualisation of everything itself became a norm, which we dignify with the word "etiquette". Any breach of etiquette ritual became inherently inappropriate, although no-one could say why, because they didn't know why themselves. They just found themselves being driven into unreasoning anger caused by withdrawal stress whenever they encountered non-compliance.

And so the process continued, with only the magicians realising what was going on, right up until the present day. One generation after a bunch of boredom addicts talking in nouned excuses turn up in a part of the world where people wear bright costumes, everyone has drab costumes on, has arbitrary robotic objectives and is talking in exactly the same way. In rich countries we addict children to boredom in infant schools instead of sweat shops, but it's the same core process. By age six a child is either boredom addicted or ready for a life of bucking "the system". Such children quickly get into trouble, because teachers are some of the most boredom addicted people in the culture. When they see a child approaching them, they naturally anticipate a dopamine rush, caused by the child's scripted exchange. If that doesn't happen they get a withdrawal stress instead of a rush, so it's hardly surprising they are quickly conditioned to dislike the child. When it comes down to it, teachers have been known to protest, "I don't like the way he sits!", as their basis for claiming that a child is mentally handicapped.

As well as the people who are lucky enough to have defective off switches, so their minds can't turn off even in the midst of a totally ritualised society, there is one other group who have the opportunity to break free of boredom addiction, and that is the elderly. Even though the conversion of economics from material to brand value and the resultant speculative departure from reality in share dealings has meant that pensions are impossible in the middle of a sea of plenty, and work has rarely involved physical labour for over a generation, the elderly are still excused work robotism on grounds of their physical frailty. This frees them from enforced robotism and gives them time to smell the flowers. On retirement, elderly people can follow one of three possible paths. Some of them die quickly. No-one has ever understood why, since the people this happens to are often in robust health and thought to be looking forward to their retirement. The reason given is usually some romantic stuff about the person "living for their work". In this context, we can see an unpleasant alternative. Perhaps some of these people are dying needlessly, because of the withdrawal stress associated with the loss of their work rituals. (If so, clinically managing the withdrawal stress with controlled doses of bingo rituals would be a simple thing to do.) Some other people go straight to replacing work rituals with bingo rituals, and stay asleep until they too, eventually die. That leaves the third group. The troublemakers who enter the state of mind known as the "second childhood". This is usually thought of as a form of dementia, where people go out wearing "inappropriate" clothing, and take to annoying activities like dragging supermarket trolleys out of rivers. It is certainly like the state of mind of a child of perhaps five years old, before chronic boredom addiction has set in, and robbed the child of its energy, inquisitiveness and sense of adventure. Those who believe the second childhood to be dementia point to a bizarre effect involving the memory of people who experience it. These people find that they can remember the days of their childhood vividly and clearly, while the rest of their lives are unclear in memory. This is taken as a sign that the person's mind is failing in some strange way. If we allow for a lifetime of boredom addiction, a much simpler explanation is possible. Healthy humans have access to all their memories, all through their lives. It's only boredom addicts who have to laboriously rote memorise everything, only to lose it later. When the elderly break out of boredom addiction, they find their childhood memories are there, fresh as they laid them down over 60 years previously. The intervening 60 years are dull because they weren't really there to make memories in the first place.

The Lebanese mystical poet Kahlil Gibran described the situation of a society imprisoned by mass boredom addiction, and the terrible loss of awareness that then occurs, due to a lifestyle that excludes the necessary level of natural stimulation required to keep the people's minds turned on, in his book The Prophet:

Would that I could gather your houses into my hand, and like a sower scatter them in forest and meadow.

Would that the valleys were your streets, and the green paths your alleys, that you might seek one another through vineyards, and come with the fragrance of the earth in your garments.

But these things are not yet to be.

In their fear your forefathers gathered you too near together. And that fear shall endure a little longer. A little longer shall your city walls separate your hearths from your fields.And tell me, people of Orphalese, what have you in these houses? And what is it you guard with fastened doors?

Have you peace, the quiet urge that reveals your power?

Have you remembrances, the glimmering arches that span the summits of the mind?

Have you beauty, that leads the heart from things fashioned of wood and stone to the holy mountain?

Tell me, have you these in your houses?