| [Last] | [Contents] | [Next] |

The human species seems to be very lucky to be alive, and the luck seems to have started long before the solar system formed. The amount of energy released by burning stars, and the length of time they burn for, is the result of a complex balance of physical constants that we determine by measuring the properties of particles in experiments. If any of these numbers were even slightly different, stars would not form, would not light up, or would only burn for a few hours. The same thing applies to atoms forming, and the kind of chemistry that is possible with atoms. If the physical constants were even slightly different, only a few kinds of atoms would be possible, and the kinds of chemical reactions they could be involved in would be so simple that living beings would not be possible. It's as if the fundamental properties of the whole universe are finely tuned to allow complex life forms to arise. This observation is called the "anthropic principle" (the belief that the universe is friendly to humans), and people who are interested in it talk about it in two slightly different ways. The "weak anthropic principle" says that the friendliness of the universe towards complex life forms is not very interesting. This is because creatures who could notice the anthropic principle could only appear in the universe if it was able to support them, so it doesn't matter how unlikely it is - we have to see the mix of physical constants that allow us to exist. If things weren't as they are, we wouldn't be here to comment on how simple the universe is.

The "strong anthropic principle" is a different interpretation of the same thing. It says, "Good grief! The whole universe is wired for life at the most fundamental level!" In all previous non-magical understanding of the universe that's a very radical idea. In the picture we looked at in Chapter 4 the strong anthropic principle isn't radical at all. It's just part of an overall picture of a universe that's been building towards greater richness and complexity all along. People who are intuitively convinced of the strong anthropic principle tend to point to other curious coincidences, and one of their favourites is the curious way the sizes of the moon and the sun, plus their distances from the Earth (which actually change over thousands of years as tidal forces steal energy from the orbiting bodies), combine to make the moon exactly cover the sun in solar eclipses, during the very era when humanity is ready for such a vast maths and physics lesson hanging in the sky. The coverage really is exact too. The brightly glowing gas that makes up the sun's disk is completely covered, and this makes it possible to view the movements of gas carried away from the surface by magnetic fields which are completely visible. Even this bizarre coincidence makes sense if humanity is evolving towards tasks considerably greater than grubbing around on the surface of one little planet. The huge science lesson in the sky is one component of a system that operates at interplanetary scales (at least) falling apart on the backwards arrow, and our species in its current state is another component.

Some people feel the idea that the apparent size of the sun and moon at this time in our evolution can be seen as evidence of anything is just too mind boggling. There's a kind of embarrassment that makes people nervous about looking into clues that are too blatant, which comes from the tendency to deny that there is an explanation for things because we don't know the explanation yet, as described in Chapter 3. So it's worth looking at another example where the lessons in an equally vast coincidence were unappreciated for hundreds of years, and the opportunity that we missed as a result.

As soon as the first approximately correct maps of the Earth became available in the 17th Century, it became obvious to anyone who glanced at them for only a moment that the coastline of South America fits into the coastline of Africa, and to a less blatant extent, the coastline of North America fits against Europe and Scandinavia. Today we know that this is because the surface of the Earth is formed of solid plates - called "tectonic plates" that move around on the molten innards of the planet. Millions of years ago all the Earth's land masses were one continent, and the forces that pushed them apart are also responsible for volcanos and earthquakes.

No-one picked up the co-incidence and ran with it for nearly 300 years. Then in 1912 an imaginative geologist called Weneger started to investigate. He found fossils of the same type of dinosaur in Africa and South America, which are found nowhere else, and this confirmed what a glance at a map of the world suggests. So Weneger published a theory which explicitly said that the continents were once all joined together, and had somehow moved apart. You might think that would have interested an intelligent species that is regularly threatened by violent earth movements and explosions of red hot magma, but it was not to be. Then in 1962, 350 years after we first saw the huge clue, another geologist called Hess was using magnetometers to investigate the magnetic field of the sea bed in the mid Atlantic. He found that in the middle of the ocean, the sea bed's magnetic field is organised in stripes. This is because the Earth's magnetic field turns upside down every few hundred thousand years (it's actually on the move at the moment), and rocks that form out of molten magma pick up the Earth's field at the time that they cool and solidify. The stripey magnetic field in the middle of the ocean showed that new rock is always being forced up from deep within the planet, making the Atlantic Ocean five centimetres wider with every year that passes. It was only when the missing piece of the puzzle was explicitly found by a person who wasn't even looking for it, that a culture which tends to deny the truth of anything that it doesn't know an explicit mechanism for could accept Weneger's suggestion. Then it was like a Wild West movie where the cowboys are playing draughts and one of them goes hop, hop, hop and takes all the other cowboy's pieces. It all dropped into place.

Despite - perhaps even because of - the size of the clue, the world's geologists didn't go and look for the missing piece of the puzzle until it turned up by good fortune. That's why we've only been able to make progress in the study of dangerous volcanos and earthquakes in the last 40 years. If we'd started a couple of hundred years earlier, we might be more able to warn people of impending earthquakes and save many lives by now. So the lesson is that we should be willing to explore vast clues instead of shying away from them. The worst that can happen is that we'll not be able to find a causal mechanism and still be puzzled, but that doesn't matter because not succeeding in science is not the same as failing - even if the deductive mind in isolation assumes it is!

From the point of view of our modern age, where we rely so much on technology, it might seem unlikely that pre-technological people could have made progress in understanding earthquakes even if they had tried. Where the people concerned are boredom addicted there may be some truth in this, but for the one person in five who retains some access to their inductive mind without even making special effort, great things are possible. In the case of plate tectonics we have evidence of this, dating back to a time before humanity lost its collective wits. The evidence is found in the legend of the dragon.

Tales of dragons are found in South America, parts of China and Wales. These are all areas where tectonic activity occurs. (Major earthquakes don't happen in Wales, but the grumblings of earth movements are often heard - particularly in Pembrokeshire.) Dragons roar and fly faster than the wind. Earthquakes propagate very quickly along fault lines, and make a lot of noise as they do so. Dragons belch fire and smoke, as do volcanos. Dragons live underground, where they guard their hoards of precious jewels. Precious jewels are formed by the vast temperatures and pressures deep underground, and are moved nearer to the surface by earth movements.

When we look at the legend of the dragon like this, we can see that prehistoric humans were much better at joining the clues together than modern humans were in 1912. The ancients could form impressions and identify related things without needing every last detail explicitly spelled out for them first, which put them in a much better position to go and find the details. When humans dumbed down (but thought they were getting smarter) they could no longer make sense of the work in progress called "dragon", so they explained it away by saying that their ancestors were stupid people who believed in non-existent animals. It's the same situation that we've seen many times before. Once we've seen what is there we can go round sticking labels on what we've seen. When we try to do things the other way around (as the deductive mind acting alone must always do), we simply enclose ourselves in our own ignorance.

When we look at the fossils of early humans and the bodies of modern humans, we find plenty of evidence that our species has had a difficult time of things throughout its entire evolutionary life. We know that creatures we can identify as our ancient ancestors arose in Africa during a period when it was densely forested. They were nearly wiped out when the climate became hot and dry, the forests disappeared and food became hard to find. They survived though, because some of them learned to stand erect on their hind legs. This reduced the surface area of their bodies that they exposed to the scorching sun overhead and helped keep them cool. It also raised their heads above the scrubby vegetation. This helped them see more possible food as well as predators, and left their forepaws free to become more nimble. Having their heads up in the breeze gave them an opportunity to cool some more, which we can see because they evolved blood vessels that passed outside the protection of their skulls. That's a crazy thing to have unless a creature has a cooling problem - the only other animals we know of that did this are some dinosaurs that are thought to have had cooling problems. To exploit the cooling tower on top of their necks they started expending more of their precious energy (food was scarce with the forests gone) pumping blood up to their heads. Now they had a lot to look at and good blood supply to their brains, so it was cost effective for their brains to get bigger and make good use of all the visual data they could gather.

Up until now the tale is no different to the story usually told by many modern archaeologists who have studied the bodies of early humans, but now we can add a twist suggested by the relationship between insight and energy described in Chapter 3 and suggest a readily available evolutionary route to the kind of heightened intuitive awareness which humans possess - when they have their minds turned on. Our ancestors had a cooling problem, lots of fractal data entering their eyes, and a big brain. The nights in their arid African climate were as cold as the days were hot, and when the fractal data held in those big brains self detected, they found they could use some of the heat that was a problem in the daytime to ease the cold that was a problem at night. The more fractal data they could find to self detect, the more they could perform exchanges of information and energy with the future. So they added remembrances of their own life experience to the fractal data coming in through their eyes, and invented contemplation. A series of chance events had led to a situation where early humanity's inductive reasoning abilities received a huge boost. In this picture our special creativity didn't happen because it produced an immediate benefit to survival compared to the other animals trying to get by in the desert, but as a side effect of using fractal self detection to keep cool in the days and warm at night!

A series of improbable but possible events had meant the Dreamtime was accessible, and humanity could use this together with physical characteristics that provided flexibility above all else to survive and thrive. The shamanic peoples such as Native Americans and Australasian Aboriginals who still use their traditional languages retain this kind of consciousness to the present time. There were still plenty of close shaves for the species to survive, and each of them increased our flexibility. Our ability to raise our arms above our heads in a way that no other monkey does but is good for swimming, the deposits of fat on our bodies, and the way we waste salt to cool by sweating all suggest that for a while we had to spend much of our time in the sea. We have no clues as to the misfortune that led to that period of new ability development. Genetic studies of mitochondrial DNA (a part of our DNA that we only inherit from our mothers) in modern humans from all over the world suggest that a few tens of thousands of years ago our species was reduced to just a few thousand individuals, and nearly became extinct! A huge volcanic explosion is the likely culprit on that occasion. Every crisis that nearly killed us developed new kinds of flexibility. We spread all over the planet, adapting, developing a digestion that can eat anything and learning to survive everywhere from the equator to the poles. In this we are different to other kinds of creatures, which have not had as hard a time during their evolution, but don't build space stations either.

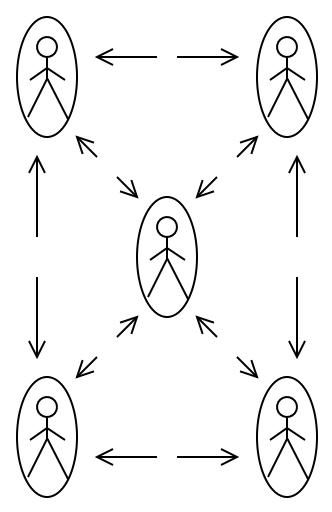

We've seen that when people become trapped in robotic behaviour and the error of the deductive mind operating alone, they end up falling into conflict with others instead of being able to co-operate. This is the difference between human business ecologies where conflict is dominant, and rain forests where co-operation is dominant but not recognised by trapped humans because the co-operation forms the background context - and that is deleted when trapped humans focus on isolated incidents of competition. We see this in workplaces dominated by proceduralist and reactive line managements, where the workers' main focus becomes avoiding blame:

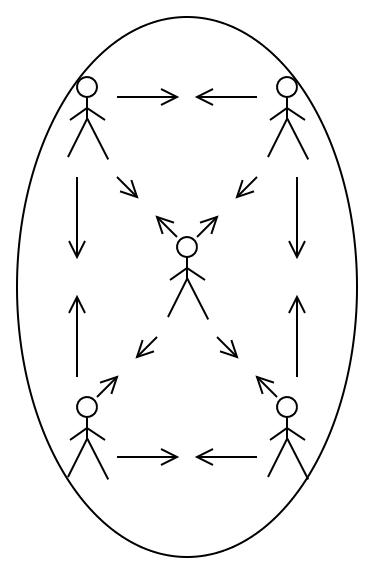

When people become focused on the part of a shared problem that they are dealing with, and shift their attention from avoiding blame to achieving success, jelled teams can form. Because the problem has its own deep structure, the whole team grows an authentic structure by mirroring the problem that does not need to be imposed arbitrarily by management. Effectiveness increases, and innovative products are designed and built at lightning speed. Turning the focus on avoiding blame inside out so that it becomes achieving success removes the system boundaries between workers and that turns everything else inside out:

It isn't just the effectiveness of jelled teams that is vastly greater than that of warring individuals. The ambitions of the team enter a different level of aspiration too. The single employee can hope for no more than being the last person to be laid off as the firm goes bankrupt, while the jelled team can aspire to Total World Domination. Creative engineering teams always aspire to Total World Domination, and wear T shirts to prove it. It's an example of an attitude called Ha Ha Only Serious. They like to misquote Robert F. Kennedy and say, "We shall do these things... and the other things... not because they are easy... but because they are fun..." This might sound like its own form of mass insanity, until we realise that the GNU/Linux operating system, and all the applications that run on it, is freely available with all source code, without cost, and has been constructed by volunteers from all over the world without any management whatsoever. According to all prior management theory, which assumes that "man is vile", this simply can't happen. Yet GNU/Linux doesn't just exist, it's the main operating system used by serious academic science sites and Internet Service Providers, and without it the modern Internet would not exist.

There is a very strange and striking example of what happens when individual organisms form jelled teams available in the life cycle of slime moulds. Slime moulds spend much of their time living as collections of single celled organisms, usually among moist grasses. They wander around their tiny territories, finding food like any other amoebas do. Then suddenly, when conditions become difficult, huge numbers of these little organisms start to get co-operative and congregate in one place. They zoom up the ladder of evolution, and literally start climbing on top of each other. As they do so their cells blend into each other (although each cell's nucleus remains distinct), and the collection of similar individuals, each freely following its own little amoeba desires, forms a single plant-like organism! Amoebas can't be very ambitious. Eating and dividing is the limit of what they can achieve, and they are limited in how much they can do that by the amount of food that is available in their little territory. They can't aspire to Total Meadow Domination. Plants are a different thing altogether. They can specialise their parts, grow to tall heights, release specialised seed cells into the local breezes, and spread themselves over vastly larger distances. And that's exactly what the slime moulds do! The spores released from the top of the plant-like communities drift off in the breeze to land far from where they started, and establish another colony of slime moulds.

We've seen that the biggest obstacle to humans forming jelled teams is the current problem with boredom addiction and inside out thinking. Even in present circumstances, strong and enlightened management in any commercial context can resist social pressures, protect and motivate the workers and create conditions where jelled teams form. Creative engineers with natural immunity to boredom addiction who can find each other with the aid of the Internet have successfully co-operated in a thousands strong management free team. What's more, we've seen that we live in a universe which is (from our point of view) constructing itself by connecting it's components in richer and more complex ways. With this background, perhaps it's not surprising that we can make sense of the history of human civilisation by assuming that humans are going to succeed (on our arrow of time) in forming a very large jelled team, which has the ability to understand and use processes on both arrows of time. Like vast numbers of piled up slime moulds behave like a single plant, this team should be thought of as a single, planet sized organism. This view of things was explored by the fossil expert and Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in his book The Phenomenon of Man. When Teilhard de Chardin looked at the fossil record, he saw lines of development pointing towards future states, which he called "omega points". He proposed that the Earth's biosphere (including humanity) was heading towards one omega point, within a universe which was itself heading towards another omega point. In an astonishing leap of insight, Teilhard de Chardin recognised the potential of the omega point idea that he had found by studying the fossil record, for integrating the ideas of science and real magicians.

Around 6,000 years ago a new and much more powerful kind of occasional disaster began to direct the development of humanity. Instead of glaciers blundering around the planet, ideas began to appear in the intuitive awareness of some humans. Instead of being a strangely organising flow (spirit) connected to the end of time, we can think of these ideas as fractal reconstructions of part of the mind (soul) of the human jelled team. An individual human's thoughts can be understood as an exchange of information and energy with itself around 12 or 36 hours in the future - the length of time the heat buffering faculty evolved to support. The Sun Absolute's thought (which provides existence to the whole of the universe) is infinitely long. The first thought of the human jelled team (which like everything else in the universe seeds its own self creation) stretched back to the time 6,000 years ago that strange new ideas began to appear.

The first new idea inspired humans to explore the possibilities of predictable, low payoff activities that can best be understood using the forwards arrow of time. This included division of labour, deskilling and mass production. As described in Chapter 1, this radical but reasonable sounding idea resulted in the first technological disaster and most of the species became trapped in boredom addiction. Intuitive awareness disappeared in most humans during childhood, and humanity was forced to develop deductive awareness and rely on processes that can best be understood on the forwards arrow of time. We began to construct the base of rational, technological culture. Population growth and recorded history began. Most humans during this distinct second age of the world could not be described as healthy. They had swapped backwards arrow awareness for forwards arrow awareness which was not in itself an overall loss (although humanity had never worked so hard for so few benefits), but they had also become robotic, afraid of novelty and deluded by the errors suffered by the deductive mind acting alone. The development of a species that would eventually be able to operate simultaneously on both arrows of time and use all opportunities to assist the growth of richness was bought at great cost for the generations of humans that would live in the second age. Fortunately the time of mass insanity would only be temporary.

Intuitive awareness was never entirely lost to the world. During the second age those societies which remained free of mass boredom addiction became a tiny minority of humans, first because of the population explosion that occurred within boredom addicted societies and later because of the unfriendly behaviour which became commonplace for boredom addicted societies encountering anyone else - boredom addicted or not. Tiny though it was, this minority never died out, and their view of reality always remained available. Within boredom addicted societies, people with genetic immunity to the condition were always being born, and were able to be be creative, proactive problem solvers. Although they were rarely appreciated within their own societies, and were often vulnerable to attack at times when economic surpluses led to chronic mass fixing of ritualised behaviours, boredom addicted societies only continued to exist because of the contributions of these people. The creatives also provided the magicians, who were able to appreciate a radically different understanding of cause and effect than the one used by the societies around them. The magicians continued to receive intuitive copies of parts of the mind of the self creating intermediate range creature, and assist in the direction of humanity's development. As well as the slow and subtle diffusion of new ideas, some magicians were responsible for more obvious kinds of directed social development, which appeared as vast movements in human culture. When the level of development could sustain it and required it for further development, boredom addicted humans started to get religion.

To many modern people, the idea that religion is a strategy to assist the development of rational culture seems ridiculous - a self contradicting statement. After all, the central feature of religion is that it is not rational! This is because religion is an ambitious kind of marketing activity which takes a powerful grip on people trapped in an unhealthy and irrational state of mind, and the religion designers' concrete and rational intent (which takes many human lifetimes to have its effect) is not included within their religions' teachings. It's more informative to look at the religions' attraction to groups of people afflicted with the problems described in Chapters 2 and 3, and the developments that actually occurred in the religions' contexts, than the irrational stories contained within the religions themselves.

The trouble with groups of people trapped in mass boredom addiction is that they lose track of their stated objectives, as repeating behaviours becomes more important than the results of those behaviours. They lose the ability to spontaneously notice that things are a mess. They "just put something and get on". They believe that so long as their behaviour has been robotic, the results - no matter how disastrous - must be inherently correct. They become introspective because of the error of the deductive mind acting alone, and think of their priorities at any time as all that could possibly be. With their ability to notice the patterns in nature suppressed, they have nothing to provide authentic common ground with others. Instead they see those who are used to boring themselves by repeating the same behaviours, slogans, and body language as inherently right, and those who repeat different behaviours as inherently wrong. It isn't possible to construct large technological societies out of people in this state, and it isn't possible for an aware few to break everyone else out of boredom addiction. It's quite possible to break a few people out of it at a time, but as soon as the workers have turned their backs, the chronic ritualism and totalitarian demands that all behaviour be ritualised made by those around the newly awoken people mean that they inevitably sink back into unawareness.

The only way out of this pickle was to leverage the problem against itself. That meant using the social alignment available within boredom addiction to compensate for the shared awareness of reality that was lost when intuition was suppressed by the addiction. By designing ritualism that was more addictive than any stuff that people had cooked up by chance and bundling it up with other ideas that would be useful, large societies could be encouraged and their development could be directed. The development of deductive culture could be driven to its conclusion, at which point the contradiction of people running around in ever decreasing circles in a sea of machine produced plenty while convincing themselves that they are on the edge of starvation would be exposed. Only then would the members of a global deductively fixated culture be able to see their situation, and their understanding of forwards arrow processes would lead them to awareness of the backwards arrow and the magicians' viewpoint.

All religions feature a great deal of ritualised behaviour. This provides an awareness reducing drug fix which seems to have self evident inherent rightness to people who are addicted to their own boredom chemistry but don't know that they are trapped in addiction. When most people lived in agricultural communities, the novelty exclusion and ritualism available in religions was greater than the boredom of farm work. Farm work's boring, but there are clods of heavy earth which make the plough kick around in random directions, birds singing in the trees, changing patterns as sunlight shines through clouds. The people were never far from the stimulation of nature that they had evolved to live with. Each week the religious rituals were the most tediously repetitive things people saw, and many religious leaders strive to clothe themselves in as boring and uniform a manner as they can. Religions began to decline from the start of the industrial era, when people living in towns and doing factory work began to find more ritualism in the factories than in religious ceremonies. For sheer mind numbing boredom, nothing can compete with modern post-industrial office rituals.

The magicians who designed religions were well aware of the psychological abnormalities of people trapped in boredom addiction and inside out thinking, as well as understanding the underlying truths of reality that had become lost to most people. They could use the one kind of understanding to trigger some awareness of the other kind of understanding, and produce perceptions and puzzles that were fascinating to most people. Religious people always talk about "symbols". When people can perceive nature directly, they don't need symbols. The famous "symbol based thinking" which is often described as a great step forward in human development is really the deductive mind's need to copy everything into it's own internal space before thinking can begin, and was not an advance at all. For the reasons explored in Chapter 3, symbol based thinking removes context and turns people's awareness inside out. When religions wrap everything in "symbols" before they start, they prepare ideas by turning them inside out before anyone looks at them. Then people with inside out minds look at the symbols, and to some extent their inside out minds turn the inside out symbols right side out again. This is as close as many people come to the kind of direct experience that people who do not erect imaginary system boundaries between themselves and the rest of the universe enjoy. So in some mysterious way they perceive the religions as containing something more real than the ground beneath their feet (as they perceive it). An impressive example of a puzzle designed for the inside out mind is found in the Christian story of the Crucifixion, and it can be examined without any need to ask whether the story is factually true. The story contains two key points:

1) Jesus was murdered.

2) He recovered.

Point 1 is not big news. Unfortunately this happens to people every day. Point 2 is a remarkable claim which constitutes the core miracle that the religion is structured about. According to the story, the murder cost him no more than 48 hours downtime - less than a heavy head cold! So why do all Christian sects emphasise 1 rather than 2? According to the religion, it is point 2 which singles Jesus out as an unusual person who should be taken seriously. So why do statues of Jesus always depict him being murdered, rather than running around and thumbing his nose at his murderers? It can't be anything to do with the murder being uncomfortable. Firemen often suffer more protracted discomfort as a result of their selfless acts on behalf of others, yet people don't feel the need to go on about it for 2,000 years. Even more oddly, even critics of the irrationality of the religion, who usually delight in pointing out every inconsistency and illogical aspect of the stories, don't notice this glaring misemphasis either. It's exactly the wrong way around, people trapped in inside out thinking as described in Chapter 3 can't see what is wrong, but they're aware that there's something odd about the story and this helps grab their attention. It's rather like the strange attention grabbing optical illusions that the artist M. C. Escher is famous for (although their structure was discovered by the mathematician Roger Penrose in his youth):

Every human being is born with the most highly developed intuitive awareness of any animal on this planet. It isn't available to most people after the age of around six years, when they become boredom addicted, reactive and stop asking "Why?". Until the age of six years, everyone has the ability to form an intuitive understanding of the world around them. After the age of six, anyone can experience intuitive awareness if their environmental novelty is sufficient for their mind to turn on. Presumably everyone who has lost their awareness of the world around them has some recollection of when the world around them became flat and dead. This provides religion designers with a third source of mind captivating power - in a deep sense, what they say is true!

There really is a creature whose presence is found in every bit of the universe, because it is fractally distributed. This creature knows everything, because it is the fully integrated version of everything that could possibly exist in the universe. Most humans are in a corrupted state which leaves them fearful, craven and dishonest, and unlike heroin junkies who at least know why they steal their mothers' furniture, boredom junkies think they're normal. The way out of their pickle is to avoid false perceptions, appreciate and contemplate the richness of the universe around them and behave constructively instead of obsessively repeating pointless behaviours. If they do that, they can reach a coherent state of mind which is a conserved structure, and this is also their natural purpose. If they don't follow their natural purpose, they don't pick up anything which is conserved. All magicians, whether they design religions or not, say the same thing. We'll see a particularly striking example of this in the next chapter.

Unfortunately people trapped in boredom addiction tend to "correct" what religion designing magicians tell them. They pervert the key ideas to justify their ritual addiction. They cook up nonsense about a Great Sky Supervisor which plays cruel tricks on them and spies on them to ensure that they are robotically complying with the fitting in despite the mean tricks. If they comply, they get beamed up to some different place which is nice instead of the horrible and dead place where they live, where they are materially rewarded for their compliance. If they fail to comply they get beamed down to some horrible place where they are tortured. Observing and understanding the details of the universe becomes engaging in sycophancy to curry favour with the Great Sky Supervisor, and it is quite pointless to look for any rational evidence for any of this - it must all be taken on "faith". Each religion claims that its pointless ritualism is the correct procedure to be followed, while all others are false.

People who are caught by religions really can benefit from them so long as they focus on the original stuff rather than the subsequent corrections, although most people don't. In evolutionary terms, this is not significant. The main intent of religions has always been long term development, and that has run it's course because we can no longer benefit from (or afford) being trapped in boredom addiction. Interactions between different threads of religion first organised large scale societies, then introduced the scientific study of the natural world into those societies which empowered them with technology, and then added concepts of balance and cycles of cause and effect to the scientific understanding. It's an unusual way to look at it, but the benefit that we get from 6,000 years of interacting religions is the ability to do things like photograph our planetary ecology from space and understand what we are seeing. The cost has been thousands of years of war, bigotry, fear, confusion and - all too often - contempt for the very reasoning mind and culture that the entire process has been developing. Now we have to drop the costs and keep the benefits.

We began this book by noticing a practical problem. The modern world needs rethinking because we are so rich. To understand this problem we have had to undertake an hermetic journey that has taken us through brain chemistry, the behaviour of huge societies and the perception of reality that they construct within themselves, the way we do "logical" thought, the structure of all of space and time, and especially human evolution. We return to our starting point with a deeper understanding of the last 6,000 years - and where we can go next.

The inspired genius who invented time and motion studies set humanity off on an hermetic journey in which we lost our innate, intuitive understanding of the universe. Because of the change in consciousness we even lost all our history until that time. Slowly - but incredibly quickly compared to all prior stages of our development - we constructed a new kind of understanding, which showed us things we had never known before. The new understanding was self-consistent, but inside out with respect to reality. This meant that the minority who retained their intuitive abilities couldn't integrate the two kinds of awareness, and they could not threaten the process of development.

Today deductive consciousness has reached a barrier of insanity everywhere it looks. The most creative children must be drugged to make them more like industrial robots - in the very era that such robots make robotic humans completely redundant. The stability of economic systems is threatened - by a scarcity of scarcity! In the midst of machine produced plenty, people "work" more hours than ever before - yet their activities are often completely unproductive. To lose just a little of the excess wealth it was converted into "third world debt", which then required the destruction of the planet's oxygen producing capacity - and to the closed system of the inside out mind, no alternative is conceivable. In science we have found insanity at the start of the universe in a moment when all that we have learned counts for nothing, insanity in quantum mechanics, and insanity in a universe that requires 99% of its contents to be completely undetectable spook matter and energy. We have discovered that we can't even pick the right door in a gameshow with our precious "logic", let alone assess the guilt of people accused of rape and murder.

At this moment of crisis we can combine all the insanities we have found, resolve them, and so complete our species' hermetic journey. We can return to the understanding of reality possessed by our ancient ancestors, but with a depth and appreciation and power which they never possessed. We can recognise and escape from boredom addiction, reactivating our intuitive awareness. We can appreciate the trap of the deductive mind acting alone, and turn it right side out. And so at last we can combine the two. The resulting kind of consciousness will be a new thing. A billion human minds are now connected together by the Internet. The same system also contains most of human knowledge. The Internet can dynamically index, organise and search the information - including information about the billion people's interests and abilities - contained within it. If slime molds can form themselves into higher order beings on their own, the new human consciousness should be able to do the same thing with the assistance of this wonderful planet spanning machine. The resulting creature will be able to look at the universe - not the world - around it and make improvements. Always, the improvements will involve increasing the richness of the universe, moving it towards its fully integrated end state. As James Lovelock suggested in Gaia, perhaps its most immediate concern will be the millions of lumps of rock and ice that are flying around the solar system, which we know have devastated the Earth's ecosystem several times already. When - not if - the next one rolls around, the creature that uses at least a billion Third Age humans as its brain will have to be ready. So long as we are careful never to point them at living things, Dr. Teller's orbital hydrogen bomb powered X-Ray lasers will be very useful - and great fun! As we build and deploy our planetary ecology's defence system, we can be sure that we will make new fundamental discoveries about the universe, and so find new possibilities opening up.

From our descendents' point of view, human history will start round about now.

| [Last] | [Contents] | [Next] |

Copyright Alan G. Carter 2003.

Disclaimer - Copyright - Contact

Online: buildfreedom.org | terrorcrat.com / terroristbureaucrat.com