Personal

Power & Freedom

Engineering

PPFE Part #1

Fundamental Question: What Revolutions are Necessary and How Can They be Engineered?

Introduction

There are three PPFE pages:

If you haven't yet done so, you may want to quickly scan all three pages to get an overall idea of what's on them.

An important purpose of this page is to persuade readers to smash any "Godologist or Governmentologist idols or icons" that may still infect their brains as "idea or meme parasites." However, some readers may not be interested in "clearing Godologist and Governmentologist crap from their minds." That's OK. You could just skim this page to look for strategy suggestions of potential use to you.

Another important purpose of this page is to persuade freedom activists to use humor and ridicule as a strategy to promote freedom. Most people like to be entertained. As suggested by the section Freud on Crowds, appealing to reason may not be an effective strategy for freedom activists. You can skim this page to look for sections on humor. You may even find something amusing!

It may be possible for freedom activists to become considerably more effective. It may even be possible to create profitable businesses, promoting freedom, and providing alternatives such as private currencies. More on this on PPFE Part #2.

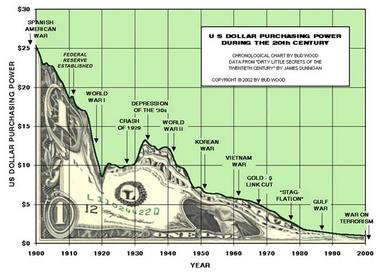

It's possible that the massive 2008-2009 bailout will result in hyperinflation, and that some financial and political systems will be greatly weakened, or will even collapse -- see Some Important Statistics.

Contents:

- Three Stages of Human Development:

- Stefan Molyneux:

- Politics on Dumbtopia;

- The Concept Factor -- Breaking the Spell

- Scientologists, Godologists & Governmentologists

- Word-Controlled Humans

- War Making and State Making as Organized Crime

- God Wants You Dead

- Take off Your Citizen Mask!

- Smash the Idols of Civilization in your Head!

- Legal Scholar Lysander Spooner Exposes the Pretended "U.S. Constitution" as a Hoax, Fraud, and Scam!

- Potential Action Based on Lysander Spooner Surveys

- Howard Bloom's Lucifer Principle

- Freud on Crowds

- The Mysterious Stranger: A Romance by Mark Twain -- Satan explains the human race:

- The Lemming Effect

- VERTICAL HUMAN DIMENSION (VHD) based on the Bicameral Model of the Mind

- Some Important Statistics

- The Monkeysphere

- War Making and State Making as Organized Crime (cont.)

- More on the Dunbar Number

- The Power of Humor

- Ray Hanania: The Power of Strategic Humor

- Bill Maher: Victory Begins at Home

- Project Lord Reincarnated Hubbard (LRH)

Stefan Molyneux:

Man, Family and State

Stefan Molyneux:

Fearing Our Parents

Stefan Molyneux:

Concept Formation

Stefan Molyneux:

Does the government really exist?

Stefan Molyneux:

Politics as addiction...

Politics on Dumbtopia

"This is one of the most delightful things I've read in a while. Thanks." -- Robert Sterling (Editor, The Konformist)

Far, far away, on the other side of the Milky Way Galaxy, there's a beautiful planet called Dumbtopia.

Dumbtopia's inhabitants are called Idiots.

They believe in a Supernatural creature they call Skybless.

Dumbtopia is divided into Dumbcountries -- at least, that's what the Idiots believe. They sporadically fight and slaughter each other over some skyblessforsaken patch of land -- "For Skybless and Dumbcountry."

Apparently, each Dumbcountry is ruled by a Plusidiot. Plusidiots are wiser than Idiots because they have blue blood -- or so they say. Common Idiots have red blood and believe that Plusidiots are their Superiors.

Apparently, each Plusidiot has a Dumbcouncil to help rule the common Idiots. Plusidiots have a secret magic drink called Etherwise. They give it to selected Idiots to drink. It makes their heads spin. After they've been drinking Etherwise for about a month, they experience Dumbliss, become Halfwits, and qualify to serve on Dumbcouncils.

Plusidiots and Halfwits pretend to have the ability to speak and write magic words called Pluswords -- Pluws for short. Common Idiots believe that Pluws are special holy, sacred words that must be obeyed. To make sure this dumb superstition sticks, Plusidiots employ Dumbcops to punish and kill Idiots who "disobey The Pluw."

Many common Idiots campaign to "Improve the holy, sacred Pluws."

Every hundred years or so, as a result of an unusual evolutionary mutation, some common Idiot wakes up and realizes that all the political systems on Dumbtopia are scams, hoaxes, and frauds. The woken-up Idiot then suggests that Plusidiots really have red blood, just like all common Idiots, and that there's nothing special about so-called "Plusidiots" and "Halfwits" -- they're really common Idiots like everybody else.

As soon as the Dumbcops discover a woken-up Idiot, they kill him or her. "Skybless help us if the Idiots ever discover that so-called "Plusidiots" and "Halfwits" are really impostors and liars -- common Idiots like all the rest -- and that their pretended "Pluws" are hoaxes... strings of dumb lies written by "clever" Pluwyer Idiots!"

Three Stages of Human Development:

- Barbarism;

- Civilization;

- Individual Sovereignty (brought about through Personal Power & Freedom Engineering).

Barbarism

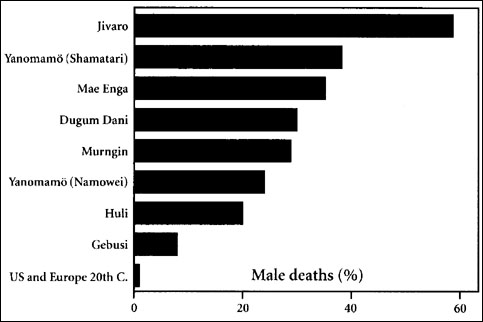

Although it may be a gross oversimplification, "barbarism" can be regarded as the "state of affairs" before humans became organized into so-called "nation states" with so-called "governments." Among many "pre-civilized" people, there was a great deal of tribal warfare. The following table is from Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. It depicts the percentage of male deaths resulting from tribal warfare for a number of primitive tribes.

The bottom item on the table is for "US & Europe -- 20th Century."

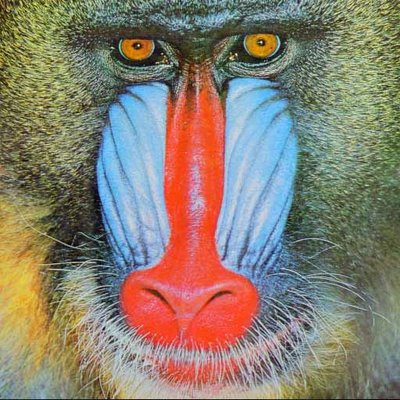

A most important "organizing principle" of Barbarism is the "Pecking Order Bully System" (POBS). You can observe POBS in action by watching wild-animal TV programs on baboons, lions, etc.

Civilization

Pinker basically argues that concentrating the use of violence in a so-called "government" is a good idea because it reduced warfare deaths by 95%. He gives a number of 100 million killed during the 20th Century by "government warfare." If it hadn't been for Civilization's so-called "nation states" and so-called "governments," the number of warfare deaths would have been 2 billion!

Steven Pinker:

A brief history of violence

According to R.J. Rummel, DEMOCIDE = MURDER BY GOVERNMENT: "Just to give perspective on this incredible murder by government [262,000,000 from 1900 to 1999], if all these bodies were laid head to toe, with the average height being 5', then they would circle the earth ten times. Also, this democide murdered 6 times more people than died in combat in all the foreign and internal wars of the century."

If you add Rummels' number for the people who died in combat to his 262 million number, you get over 300 million -- about three times Pinker's number.

"All murderers are punished unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets."

-- Voltaire

Humans in Civilizations are called "Citizens."

A most important "organizing principle" of Civilization is the "Pecking Order Bully System" (POBS). You can observe POBS in action by watching wild-animal TV programs on baboons, lions, etc. -- and by observing Citizens engaged in political elections. The 2008 election campaign between Obama and McCain was essentially the same as two (civilized) baboons beating their chests and shouting insults at each other to prove who was the "best bully."

At the end of the election, millions of Obama supporters hooted and hollered like (civilized) baboons because their favorite bully had been elected to the top of the "Pecking Order Bully System" (POBS), called the "US Federal Government." All these Citizens were completely unaware that they were unconsciously acting out their primitive and deep-seated POBS programs.

Headline in the Arizona Republic of 12/1/08: "Citizens are new slaves to government masters."

Citizens in Civilizations are partial slaves. Their bullies tell them what they may or may not eat and drink. Their bullies force them to send their children to "concentration campuses for brainwashing" -- see Dumbed Down by "Education! Their bullies force them to pay a percentage of their earnings to their bullies. If this is 50%, then the Citizens are essentially "50% slaves."

From the Preface to Foundations of Psychohistory by Lloyd DeMause: "The "psychogenic theory of history" which I set out in this book is simple to understand, though often difficult to believe. It can be summarized as the theory that history involves the acting-out by adults of group-fantasies which are based on motivations initially produced by the evolution of childhood."

It may be difficult for many (civilized) grown-ups to confront the proposition that much of what they regard as "rational life activities" could be better described as "adults acting-out group-fantasies rooted in maltreatment and abuse during childhood, as well as stemming from primitive animal programs in their brains!"

"...[R]eligions are best envisioned as a socially constructed haven for delusions that are not diagnosed as insanity due to majority acceptance. Those same beliefs would, however, receive the diagnosis of insanity if they were to appear outside of a religious framework." -- John F. Schumaker (The Corruption of Reality: A Unified Theory of Religion, Hypnosis, and Psychopathology)

Consider the proposition that 100% of "human religious belief and behavior" constitutes the pathological acting-out of group-fantasies!

Book: Wings of Illusion: The Origin, Nature and Future of Paranormal Belief by John F. Schumaker. Review on Amazon.com by Charles D. Hayes: "Understanding the nature of human belief systems is one of my principal preoccupations. I've read scores of books on this subject, and find John F. Schumaker to be in a league of his own in this discipline. He writes about beliefs with as much insight and clarity as Bryan Magee does with the complexities of philosophy. This book is timeless."

Book: The Corruption of Reality: A Unified Theory of Religion, Hypnosis, and Psychopathology by John F. Schumaker. Review on Amazon.com by Yahzi:

"This book is the most important book of the entire 20th century. Like Freud, it will define the next 100 years of psychological thinking. Unlike Freud, it will last beyond that, becuase it is more than visionary, it is also grounded in hard science.

If you ever wanted to understand how educated, rational adults can believe in the stupidist things imaginable, this book explains it.

The only weak point of the book is the final chapter, where Schumaker suggests we create a false religion to safely guide people's evolutionarily inescapable stupidity. This is John's own corruption of reality: thinking that we can actually find a painless solution. But he presents it half-heartedly enough that I think even he understands it will never work.

The only solution is expecting people to grow up and act like adults. Life isn't what you wanted it to be -- tough. Deal.

To put it another way: when you think about it long enough, this book explains 9/11, why we are in Iraq, and the current flap over Intelligent Design. That's a heck of an accomplishment for a book written many years ago."

Does the Schumaker quote on religion also apply to politics?: "Politics is best envisioned as a socially constructed haven for delusions that are not diagnosed as insanity due to majority acceptance. Those same beliefs would, however, receive the diagnosis of insanity if they were to appear outside of a political framework."

Consider the possibility that Citizens in Civilizations tend to suffer from religious and/or political delusions that result in some unpleasant consequences... including over 300 million violent deaths during the 20th Century.

Consider the proposition that 100% of "human coercive political behavior" constitutes the pathological acting-out of group-fantasies!

Individual Sovereignty (brought about through Personal Power & Freedom Engineering)

One of the purposes of this page is to persuade individuals to become "Personal Power & Freedom Engineers" (PPFEs). This may involve several steps. It is up to each prospective PPFE to decide which steps he or she needs to take to become a PPFE:

- Increase level of personal success as suggested by the GRSS;

- Raise your Mood Level and Improve Health;

- Develop Online Moneymaking Skills (or any other moneymaking skills largely or completely free from the savage shackles of Civilization);

- Improve thinking skills, starting with Project Learn to Think;

- Clear all religious nonsense, superstitions, and delusions from own mind;

- Clear all political nonsense, superstitions, and delusions from own mind (note that this may be 10-100 times as challenging as the previous item);

- Develop "practical freedom skills" -- how to live free in an unfree (civilized) world;

- Develop the kind of Champion Mindset that Jack Johnson had;

- Become More Conscious, following the example of Steve Biko;

- Team up with other Personal Power & Freedom Engineers to implement PPFE Actions (what these actions might be is open for PPFEs to decide).

Scientologists, Godologists & Governmentologists

A distinction can be made between "Mild Cults" -- involved with the killing of maybe fewer than 1,000 people -- and "Major-Killer-Cults" -- involved with killing tens of millions of people or more.

Under "Mild Cults" could be included Scientology and Scientologists (killed maybe about 100 people in 50 years) and Jonestown or "People's Temple" (killed about 900 people).

A PPFE may regard Scientology and Scientologists as at least mildly crazy.

Under "Major-Killer-Cults" could be included Godology and Godologists (killed at least tens of millions of people) and Governmentology and Governmentologists (killed over 300 million people during the 20th Cntury). The picture is complicated by the fact that many Governmentologists are also Godologists.

Because of the violent deaths resulting from their beliefs and behavior, a PPFE may regard Godology and Godologists as much crazier than Scientology and Scientologists.

For the same reason, a PPFE may regard Governmentology and Governmentologists as about ten times crazier than Godology and Godologists.

On Dr. Arthur Janov's Primal Healing website under "Books" and Beyond Belief! could be found on 11/11/08 (minor edits):

"This book examines what forces in us drive us to believe in mystics, healers and gurus. What unconscious impulses lead us to join cults, and reveals how feelings become beliefs in the brain. Dr. Janov discusses all of this through the autobiographies of patients who have lived it. He also examines how the government functions as a cult with the same dynamics as any cult leader from Jim Jones to Rajneesh and to Bin Laden.

There is a chapter on the born again, conversion experience and why that happens. Another on what makes a leader or healer and what makes a follower. He cites many research studies on how thinking something will kill pain actually does, and why that happens. He analyzes belief systems and how they function to keep us comfortable. That the brain doesn't care if it is Islam, the Republican Party or "the secret," it all works the same in the brain. What he points out is that the thought of a deity makes us believe in it whereas it is the thought itself that relieves and soothes us.

This is the first thorough account of how beliefs work in the brain to bring us comfort and calm. But it is a spurious calm since there is a seething cauldron of pain that lies below beliefs that will make us sick and shorten our lives."

A great deal has been written about the characteristics of cults. The following apply for our purposes:

- Messianic, possibly maniacal, authoritarian bully-leaders who regard themselves as "popes," "presidents," "great deciders," (and/or other similar terms) and who claim that they "represent god," "consult with god," "have unique keys to higher knwledge," "are authorized by the constitution," "have a mandate from the people," etc. (Sometimes the same bully-leader is both a Godologist and a Governmentologist!)

- Hierarchical, coercive control structures -- Pecking Order Bully Systems (POBSs).

- Top cult staff members are selected primarily for their loyalty, and from whom very little dissent is tolerated. (Obama's first appoinment was Emanuel, generally regarded as "hard-nosed" and "sharp-elbowed," i.e., an effective bully!)

- Some specially selected cult staff members perform all kinds of secret activities (often criminal), not communicated to the general membership.

- Dissenting cult staff members are usually kicked out.

- Cult leaders lie about their agendas and actions. (Governmentologist leaders are often controlled by Big Business interestes. Obama and his buddies paid hundreds of billions to insurance giant A.I.G. and to other Big Businesses.)

- Deception and/or force is used by Governmentologists to gain new recruits -- also called "compulsory education" -- the deception includes not revealing to the victims that the purposes of their "education" include turning the victims into compliant factory or office workers, subservient "citizens of their cult," and/or obedient soldiers brainwashed to kill and be killed in wars organized for phoney reasons to benefit the businesses of cult leaders and their friends. Typically, Godologists use deception by making absurd promises of "eternal salvation." In some cases, they don't reveal that one of their purposes is to gain new recruits to ensure the availability of children for sexual abuse.

- New recruits are removed from their families for long hours, kept confined in artificial environments ("schools"), where they are systematically dumbed down and brainwashed to "believe and obey authority."

- Recruits are also brainwashed to become dependent and to believe that Governmentologists have "Godlike" powers to make a wide range of decisions for them and to "do for people what they can't do for themselves." Godologists use similar brainwashing techniques to make people dependent by using fear tactics, e.g., "eternal damnation," "burning in hell," etc.

- Members are compelled (at the point of a gun if necessary) by Governmentologists to pay large portions of their earnings to cult leaders. Godologists typically use less violent methods, but still fraudelent, to obtain unearned money from their victims.

- Some Governmentologists don't allow their members to leave their cult, in that they have to continue paying large amounts to the cult leaders, no matter where the members go. Godologists typically use fear tactics to prevent their cult members from leaving.

PPFEs involved in promoting freedom may be able to use strategies suggested by the above to good effect. They could condemn Scientology as a crazy cult... and then condemn Godology as and even crazier cult... and then condemn Governmentology as the craziest cult of all!

See also: Project Lord Reincarnated Hubbard (LRH).

Word-Controlled Humans

Following are extracts from the book Word Controlled Humans by John Harland:

THE FORK IN THE ROAD

"Words can be used to tell others what an individual perceives; they can also be used to override perception, condition or destroy thought, and control humans. When the first word trails were being made in the expanding growth of conscious ideas, there was a fork in the road of possibilities. The majority of humans turned off in a direction that has now been made into a broad highway. Nature's method of making individual perception a major factor affecting survival was the way rejected; acceptance of the individual by a word-conditioned group was made the dominant requirement affecting the individual's survival. As I see it, the fork we have taken can lead only to human extinction or biological regression; the other could have led to further evolutionary advance. I want to contrast the two directions, recommend the other fork, and set forth a procedure for getting over to it..."

"The idea implied by "authority" triggers action in those who have been word-conditioned to set aside their own innate will and accept the word-control of someone in "authority." As I see it, "authority," implying the "right" of individuals or groups to control or exercise power over others, has no meaning in the world of reality. I want to identify it as highly suspect by always enclosing it in quotation marks...."

"When orders were obeyed because coming from someone having "authority," mass warfare between groups of word-controlled people became the standard practice..."

"When humans create words that do not refer to a perceivable reality, there is likely to be confusion between the man-conceived fictional entity and something clearly perceived which is real..."

The fork taken by PPFEs is to primarily use their senses to discern reality. The other fork is to primarily use "subjective social agreement" to discern reality. PPFEs are very interested in words with physical referents that can be perceived by using their senses. Godologists and Governmentologists typically use words with no physical referents to control, subjugate, dominate, and exploit their victims.

"Man has such a predilection for systems and abstract deductions that he is ready to distort the truth intentionally, he is ready to deny the evidence of his senses only to justify his logic." -- Dostoevsky

Following are extracts from the book From Freedom to Slavery: The Rebirth of Tyranny in America by Gerry Spence:

"The breathing dead witness the murder of themselves. The breathing dead live within their own corpses, a horror beyond description, a horror that bears the agony of both murderer and victim and suffers the indescribable pain of the last rejection, of the self against the self..."

"The concrete boxes in which children are imprisoned will explode..."

"These Earthlings are insane according to their own definition -- dissociation from reality. Existing in nearly total fantasy, they murder each other over imaginary icons and destroy entire segments of their societies over beliefs founded in myth. Nowhere in the universe have we encountered such an abdication of reason than among the natives on Earth..."

"However, Earth provides a valuable laboratory by which to study the phenomenon of "teachable psychosis." Earthlings instruct their offspring that various myths are fact, that certain fables are historically true, that divers fictions and fairy tales must be believed, thereby rendering entire populations, by definition, mad. Heretofore we had believed insanity to be the product of informities of the central nervous system, but our observations of these Eathlings have demonstrated that insanity can be taught, that the psychosis that predominates the Earth is, in major part, a phenomenon of programming, a process the Earthlings themselves understand metaphorically as "brainwashing."..."

"Although the term "freedom" eludes precise definition, for what seems freedom for some becomes tyranny for others, yet quite inexplicably these Earthlings fight for freedom, die for it, make speeches about it and even celebrate a day in its honor, all the while understanding little if anything about this elusive notion. Moreover, many believe they are free when, in fact, they are bound in the most abject servitude imaginable..."

"In the end, the most deadly trap of all is a brainwashed mind, for the brain, washed against itself, is powerless..."

"Religions! Ah, what religions do to us! How they supplant thought! How they fence out reason! How they render us impotent! How they poison us..."

"I remember when I began to feel my own power. Somehow I had discovered the King within -- the King of self. I was fearful of the King, in awe of him. Yet in his presence I felt no servitude... I felt as if I could conquer any obstacle... I shudder to think what might occur if all of the earth's people awakened their own inner Kings. This much I can predict: Magically, overnight, the world would be free."

"When we acknowledge the kingdom of the self, we will no longer accept slavery either for ourselves or for others, no matter how it is disguised, for the King cannot tolerate slavery. When we acknowledge the kingdom of the self, we will no longer tolerate untruths, for the King cannot to;erate manipulations and lies. When we acknowledge the kingdom of the self, we will no longer permit the children of the world to be tarred with fear and feathered with guilt, for the King cannot tolerate such abuse of the world's children. And when we stop abusing our children we will finally enjoy peace..."

It may be more appropriate to replace the word "King" above with "Sovereign Individual."

In Chapter 8 -- "Keeping It All in Place" --of his book Restoring the American Dream, Robert J. Ringer refers to "The Arsenal" of words and phrases used by Governtologists to keep their Pecking Order Bully Systems (POBSs) in place. He analyses the following: "The people," "the public," "society," "government," "country," "taxation," "conscription" (the draft), "loophole," "windfall," "inflation," "patriotic," "apathetic," "obligation," "duty," "decent," "fair," "justice," "public morals," "public good," "public property," "public justice," "public interest," "good of society," "well-being of society," "welfare of society," "duty to society," "obligation to society," "good of the people," "welfare of the people," "rights of the people," "the people have chosen," "fair pay," "decent living," "your fair share," "moral duty," "And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country," "love it or leave it," and "all power to the people."

For a general analysis of words used by Governtologists to keep their Pecking Order Bully Systems (POBSs) in place, see The Anatomy of Slavespeak.

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz has written a great deal about the use of words by Governtologist "mental-heath" pratitioners to establish, maintain, and strengthen their Pecking Order Bully Systems (POBSs) -- Thomas Szasz and Slavespeak.

Several authors -- including Peter Breggin (Medication Madness) and Peter Schrag (Mind Control) -- have written extensively on the use of words and drugs by Governtologist psychiatrists and psychologists to achieve mind control over their victims.

The Concept Factor

-- Breaking the Spell

Extracted and adapted from the original article -- © Robert Fritz 2006 -- that used to be on his website.

In his new book, philosopher and co-director of Tufts Center for Cognitive Studies Daniel C. Dennett describes an ant climbing up a blade of grass, but then falling, climbing up again, falling, and so the cycle continues. Dennett asks: "What benefit is the ant seeking for himself?" As it turns out, there is no biological benefit for the ant. Rather, its brain has been commandeered by a tiny parasite, a lancet fluke (Dicrocelium Dendriticum) that needs to get itself into the stomach of a sheep or cow in order to complete its reproductive cycle. The parasite is driving the ant into position to benefit its own offspring, not the ant's. Dennett points out that similar manipulative "hitchhiker" parasites infect many species, all for the benefit of the guest, not the host.

"Does anything like this ever happen with human beings?" Dennett asks. "Yes indeed," he answers. According to Dennett, concepts can act like parasites. "The comparison with which I began, between a parasitic worm invading an ant's brain and an idea invading a human brain, probably seems both far-fetched and outrageous. Unlike worms, ideas aren't alive, and don't invade brains; they are created by minds." Dennett goes on to show how "ideas and parasites have remarkable commonalities, including that ideas are spread from mind to mind, surviving translation between different languages, hitchhiking on songs and icons and statues and rituals, coming together in unlikely combinations in particular people's heads, where they give rise to yet further new 'creations,' bearing family resemblances to the ideas that inspired them but adding new features, new powers as they go." These parasitic ideas have their own agendas, ones that are independent from the health and well-being of the person. Some ideas obsess the brain, and their own cause can become more important than that of the individual host.

Entitled Breaking The Spell -- Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, the book is gutsy in that Dennett puts the phenomenon of religion under a scientific microscope. While his basic question is why do human beings have the instinct to adhere to religious doctrines, he is not attacking religion -- although some might think that asking questions about religion itself is an attack. His exploration is fair, open, and challenging. And his subject is timely in this day and age in which, in the name of religion, people prove themselves to be capable of the most repugnant behavior.

Dennett's subject is... about how and why people adopt religious dogmas, particularly when they may be harmful to the person who holds them...

What is of so much interest to me is Dennett's thesis that concepts can function as parasites that have their own agendas, their own aims, their own motivations -- ones that are independent from the benefits of "the host." This insight is consistent with some of the structural phenomena we have seen over the years, and why people can have patterns in which hard won success is eventually reversed to the detriment of the person him or herself.

Structural Dynamics [See Organize Your Life to Create Structural Tension so the Path of Least Resistance Leads You Where You Want to Go.]

A person's underlying structural dynamics determine his or her behavioral tendencies. One way that I have described this is by pointing out that energy moves along the path of least resistance, and that underlying structures will determine that path. Water flows where it most easily goes, and the riverbed -- the underlying structure -- determines that path. If the underlying structure remains the same, and if you are in an oscillating structure, your successes eventually will be neutralized. With a change of underlying structure, new possibilities emerge, and success does succeed both short and long-term. Life takes on a new direction and you experience momentum rather than inertia.

What Do Concepts Have To Do With Structure?

Oscillating structures are made up of three elements; advancing structures are made of only two. Advancing structures consists of the desired outcome in relationship to the current state: in other words -- structural tension. But oscillating structures have a third element: the various concepts the person holds.

These concepts fall into three major categories: fear of imagined (not real) danger; personal, social, or existential ideals; worldviews that explain the true mysteries in life, such as religious and metaphysical concepts that demand belief and compel certain behaviors. This third category is the one that concerns Dennett. Yet his notion of parasitic ideas might be extended to also include the other areas of concepts, such as ideals and conceptualized fears. These concepts do, indeed, have their own agendas that are independent of the "host" and do not advance the health and well-being of the person who holds them.

What we have discovered through structural consulting is that it is not the actual content of the concept itself that causes an oscillating structure. It is the way the concept is held, the way the concept takes hold of the mind, the dynamic of the concept in relationship to a person's aspirations, values, and reality. Dennett's focus on "belief in belief" seems to point to why a concept can function as a type of parasite.

A Change of Underlying Structure

Over the years, we have seen the remarkable, almost miraculous change of a person's life's possibilities when there is a change of underlying structure. The change invariably comes when a concept that was once built into a person's underlying structure is no longer part of that structure. the belief in the belief is gone. The "spell is broken." This is not a subtle change. Often people feel a weight lifted from their shoulders and a new sense of energy flowing through them. Their life patterns change and now they are in a position to organize their lives around their highest aspirations and deepest values. Their possibilities of success increase dramatically. Their patterns change from oscillation, in which success is reversed, to advancement, in which success becomes a platform for future success...

See also "Plato truth virus."

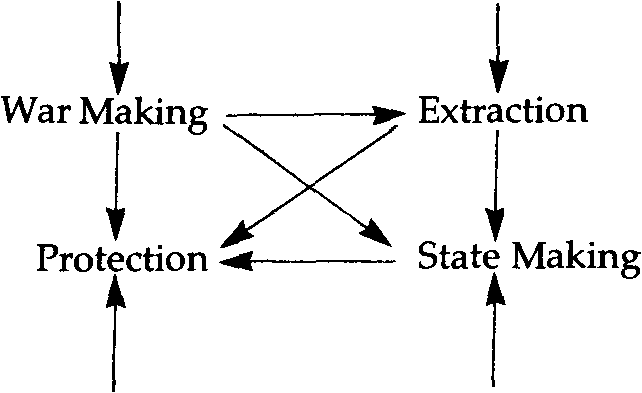

War Making and State Making as Organized Crime

by Charles Tilly

A Chapter from Bringing the State Back In, edited by Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

(Charles Tilly taught at the University of Delaware, Harvard University, the University of Toronto, the University of Michigan, the New School for Social Research, and Columbia University. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the Sociological Research Association. See also: Charles Tilly in Wikipedia.)

If protection rackets represent organized crime at its smoothest, then war risking and state making -- quintessential protection rackets with the advantage of legitimacy -- qualify as our largest examples of organized crime. Without branding all generals and statesmen as murderers or thieves, I want to urge the value of that analogy. At least for the European experience of the past few centuries, a portrait of war makers and state makers as coercive and self-seeking entrepreneurs bears a far greater resemblance to the facts than do its chief alternatives: the idea of a social contract, the idea of an open market in which operators of armies and states offer services to willing consumers, the idea of a society whose shared norms and expectations call forth a certain kind of government.

The reflections that follow merely illustrate the analogy of war making and state making with organized crime from a few hundred years of European experience and offer tentative arguments concerning principles of change and variation underlying the experience. My reflections grow from contemporary concerns: worries about the increasing destructiveness of war, the expanding role of great powers as suppliers of arms and military organization to poor countries, and the growing importance of military rule in those same countries. They spring from the hope that the European experience, properly understood, will help us to grasp what is happening today, perhaps even to do something about it.

To continue, Click Here.

In addition to many benefits provided, the book God Wants You Dead may aid you in Smashing Idols in Your Head!

Reading the section on "Pretendities" may also help you to Smash Idols in Your Head!